Copyright page

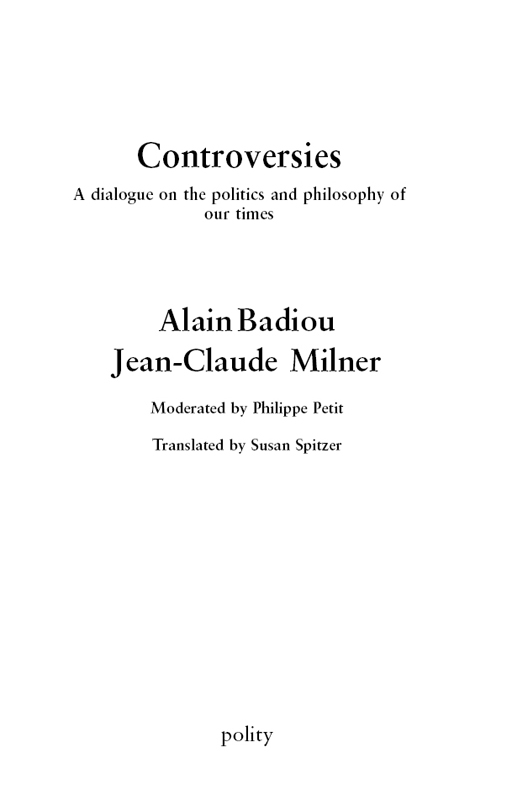

First published in French as Controverse ditions du Seuil, 2012

This English edition Polity Press, 2014

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-8216-7

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-8217-4(pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 11 on 13 pt Sabon

by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in Great Britain by T.J. International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

Unreconciled

Philippe Petit

Here are two giants, two French intellects who are frequently denounced, and never for the same reasons. They met in 1967, during the Red Years in Paris. Badiou was a lyce teacher at the time; Milner had just returned from a year at MIT. The former is now the most widely read contemporary French thinker abroad; the latter, who is largely unknown there, has become a leading intellectual figure in France.

Both share an unconditional love for the French language and its own particular dialectic. They hadn't compared their careers and ideas since they broke off relations in 2000 as a result of an article by Alain Badiou in the French daily Libration that had rubbed Jean-Claude Milner the wrong way. In that article, Badiou had lampooned the trajectory of Benny Lvy (19452003), a former comrade-in-arms and friend of Milner who had gone, as is well known, or as he himself put it, from Moses to Mao and from Mao to Moses. They had never really discussed their differences in such a head-on way.

So there was nothing inevitable about the exchange the reader will find in these pages between Alain Badiou, born in 1937 in Rabat, Morocco, and Jean-Claude Milner, born in 1941 in Paris. It might well have broken off as they went along. It was therefore agreed by both parties that it would be carried out to its conclusion, that they wouldn't let it get bogged down in posturing, and that it would deal as much with the issues of our times as with each one's system of thought. It would moreover be an opportunity for them to set out their quarrels over time and justify their assumptions. And, finally, it would provide a summary, when read, of the differences between the speaker and the spoken to, without ever losing sight of those they were addressing.

To that end, a protocol had to be established. It was decided that we would meet four times, between January and June 2012. During the first three sessions we sat on a sofa and armchairs and, during the last one, around a table, something I had requested in order to vary the mode of interlocution and to be able to spread out my papers but in reality so as to moderate the dialogue as much as possible. Jean-Claude Milner wryly remarked that he was afraid of being devoured by this system, the way Kierkegaard was by Hegel. Was it because of the table? The nature of the topics covered? Whatever the case, the last session was by far the most relaxed one. During the conversation and it really was one they treated each other with kid gloves.

These meetings had been arranged over a lunch during which a short summary of the points of friction between the two thinkers was addressed. The infinite was one of them, as were the universal and the name Jew. But the discussion turned fairly quickly into a high-quality international press review.

The scene could have been set in an embassy library, but it actually took place in a restaurant near Notre-Dame. Alain Badiou and Jean-Claude Milner had just gotten back in touch with each other. That day, they exchanged their views on Germany and Europe, American campuses, and French political life, though they didn't bring up the Middle East. It didn't matter, however, since the dialogue between them, focusing on theoretical issues and based on concrete analyses, had been renewed. All that needed to be done was to guide and moderate it to keep it from going awry.

The sessions lasted three hours each and took place as agreed. Rereading the discussions proved to be a particularly fruitful task. Each of the authors reviewed and revised his contribution, leaving the rhythm of the discussions unchanged but making the wording clearer in some places.

In the transition from the spoken to the written word each one's arguments were tightened and their positions made more forceful. The conversational tone, in which long developments alternated with snappier, more staccato-like responses, was nevertheless preserved in the final product, which reflects the quality of the listening, the sense of surprise, and the desire to convince that had emerged in the face-to-face meetings.

For if there is no thinking without a division at once internal and external to the subject, just as there is no violence that is not both subjective and objective, there can be no true dialogue unless the assumptions and method of each of the participants are broached. Just being opposed to each other is not enough; the other person still has to be convinced, and, when that can't happen, simply defending oneself is not enough; one must be able to justify the grounds for one's arguments. This, I believe, is something that Alain Badiou and Jean-Claude Milner pulled off perfectly in this dialogue. They argued, very heatedly at times to the point of requesting that a postscript be added regarding what bothered them the most, namely, their respective positions on the State of Israel and the situation of the Palestinians and they went head to head on key issues, such as the status of the universal, the name Jew, mathematics, and the infinite. But they also pooled their opinions, or, rather, harmonized their thinking, on a number of points having to do with the legacy of revolutions, Marx's work, international law, the Arab uprisings, the historical situation of France, the role of the parliamentary left, the so-called normal presidential candidate, the Indigns movement, Nicolas Sarkozy's legacy, and many other issues as well.

They agreed, as it were, on their disagreement and didn't hesitate to agree on everything else. They had to do so, in order to avoid taking the easy way out and creating the impression that there was some subtext of friendly understanding between them to set off each of their careers to advantage. For it is a given of French intellectual history that it is unlike any other. It is not better than the others, nor does it reflect an indifference to anything foreign, but it is driven by its own principle of division. Thus, Descartes that French knight is no more French than Pascal, and Rousseau, in terms of his language, is no less so than Voltaire,

Next page