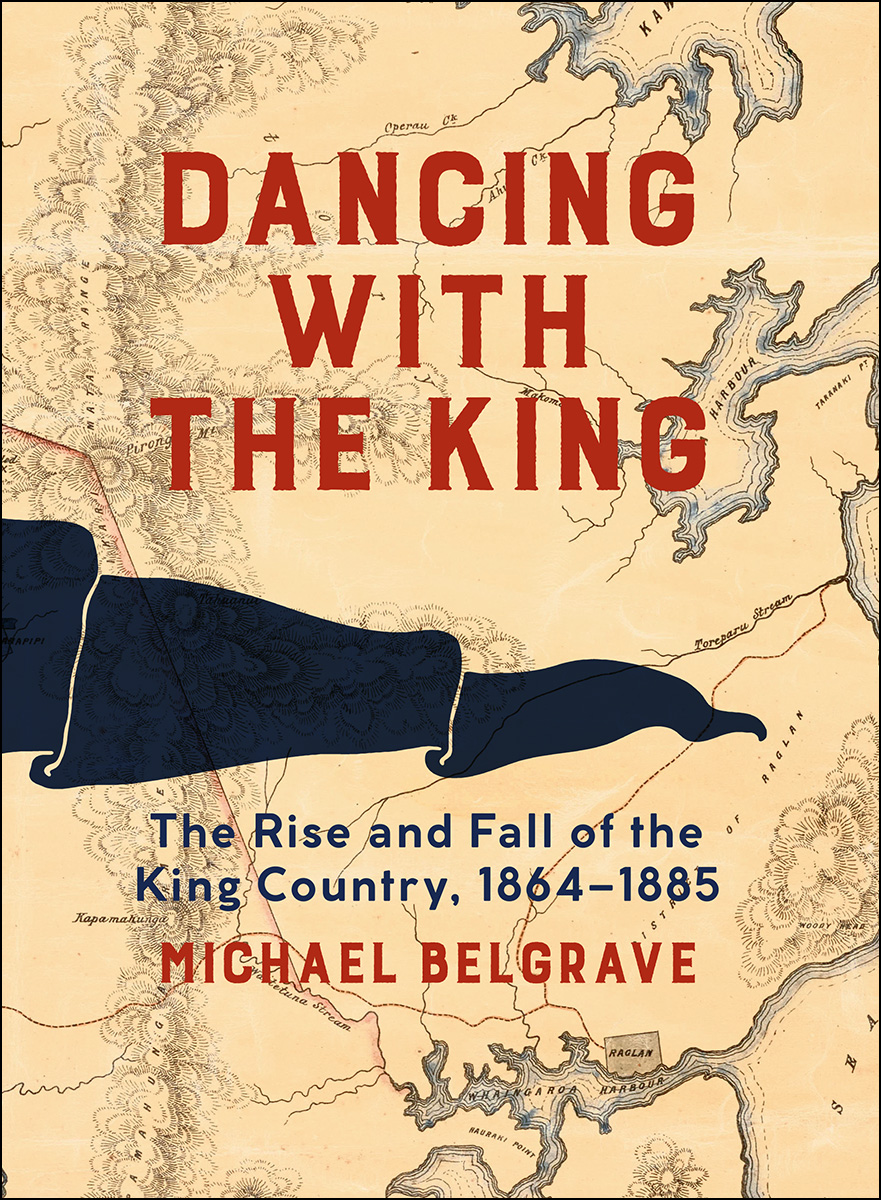

After the battle of rkau in 1864 and the end of the war in the Waikato, Twhiao, the second Mori King, and his supporters were forced into armed isolation in the Rohe Ptae, the King Country.

For the next twenty years, the King Country operated as an independent state a land governed by the Mori King where settlers and the Crown entered at risk of their lives. Dancing with the King is the story of the King Country when it was the Kings country, and of the negotiations between the King and the Queen that finally opened the area to European settlement. For twenty years, the King and the Queens representatives engaged in a dance of diplomacy involving gamesmanship, conspiracy, pageantry and hard-headed politics, with the occasional act of violence or threat of it. While the Crown refused to acknowledge the Kings legitimacy, the colonial government and the settlers were forced to treat Twhiao as a King, to negotiate with him as the ruler and representative of a sovereign state, and to accord him the respect and formality that this involved. Colonial negotiators even made Twhiao offers of settlement that came very close to recognising his sovereign authority.

Dancing with the King is a riveting account of a key moment in New Zealand history as an extraordinary cast of characters Twhiao and Rewi Maniapoto, Donald McLean and George Grey negotiated the role of the King and the Queen, of Mori and Pkeh, in New Zealand.

Michael Belgrave is a professor of history at Massey University, the author of Historical Frictions: Maori Claims and Reinvented Histories (Auckland University Press, 2005) and From Empires Servant to Global Citizen: A History of Massey University (Massey University Press, 2016), co-author of Social policy in Aotearoa New Zealand (Oxford University Press, 2008) and coeditor of The Treaty on the Ground: Where We Are Headed, and Why It Matters (Massey University Press, 2017). Previously he was research manager of the Waitangi Tribunal and has continued to work on Treaty of Waitangi research and settlements, providing substantial research reports into a large number of the Waitangi Tribunals inquiries. He received a Marsden Fund award in 2015 for a re-examination of the causes of the New Zealand wars of the 1860s.

Contents

Guide

Page List

DANCING WITH THE KING

The Rise and Fall of the King Country, 18641885

MICHAEL BELGRAVE

Dedicated to

Alan Ward

19352014

CONTENTS

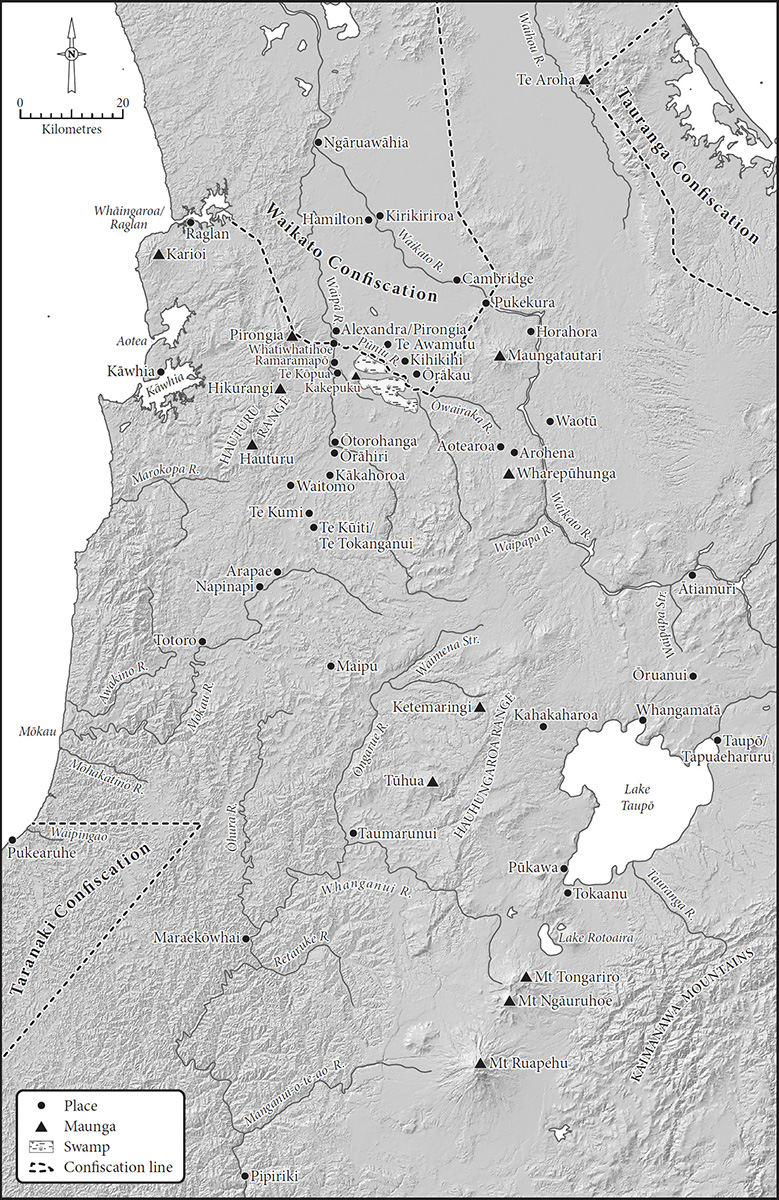

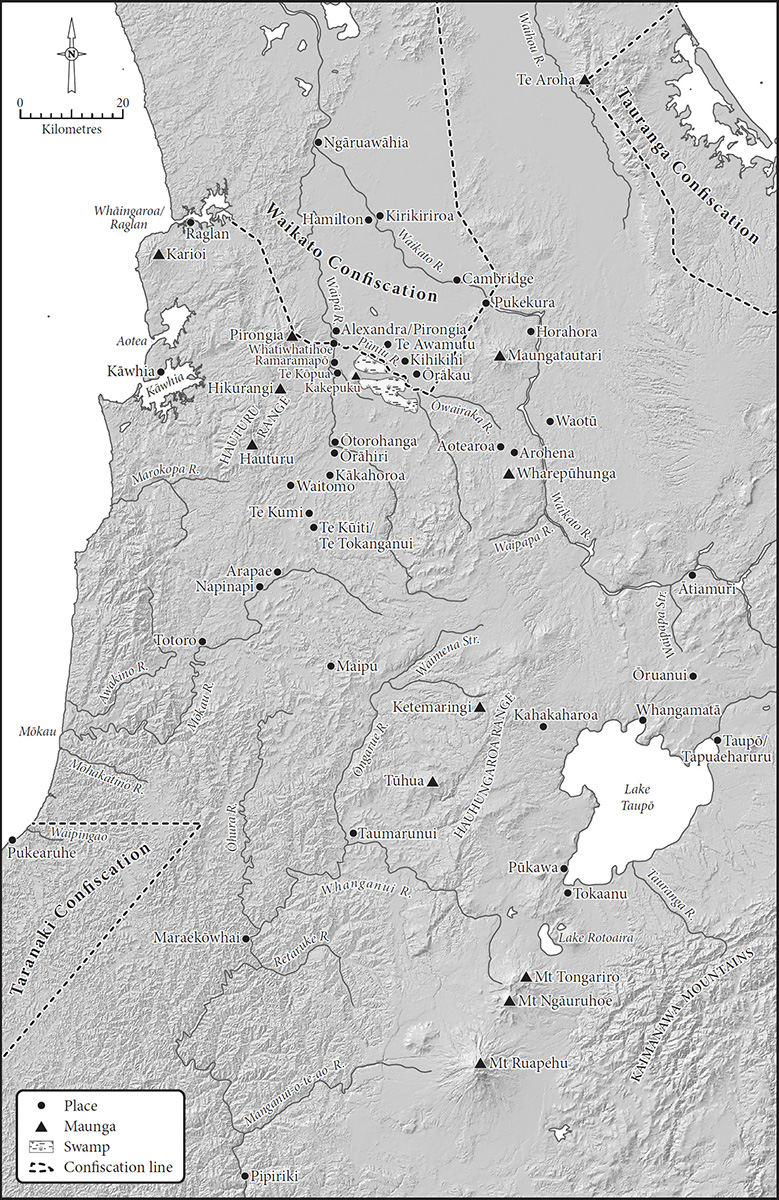

Map 1: Te Rohe Ptae

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are many people who have helped make this book possible. Grant Young, who has worked with me on Treaty of Waitangi issues for almost two decades, has engaged in spirited discussions of the issues surrounding the Rohe Ptae and the nature of Waitangi Tribunal work. Nigel Te Hiko, Chris McKenzie and the other members of the Raukawa negotiating team provided able guides to this books initial explorations. Work with Rhe Potae claimants from Ngti Maniapoto, Ngti Apakura, Ngti Toa and Ngti Hikairo, although not directly concerned with the decades after the Wars, helped me to understand these iwi perspectives on the Kngitanga and the events and locations described in this book. Work with claimants from Taumarunui, from Ngti Maniapoto and Ngti Hau, provided some insight into the southern portion of the Rhe Potae, an area which too rarely enters into this narrative. A wide range of libraries and museums have also been helpful, including Massey, my own university, the Alexander Turnbull Library and the Hamilton Public Library. The Waikato and King Country are superbly served by museums and libraries, such as those in Cambridge, Te Awamutu and Kihikihi. Their staff and volunteers work every day with the ongoing divided legacy of colonisation and settlement. I owe a debt to the many students who have endured my enthusiasms and contributed to my thinking, especially Moyra Cooke, and to Richard Boast whose comments on the draft were extremely helpful. My thanks also to the President and Fellows of Wolfson College, Cambridge, for their visiting fellowship, allowing the writing to begin. Without the work of many researchers contributing to the Waitangi Tribunal inquiries in the Rohe Ptae and in the settlement negotiations for Raukawa, this book would have taken much longer. Cathy Marrs collection of primary sources for the Rohe Ptae inquiry has been invaluable. The commitment of government to the digitisation of Papers Past and the Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representative has made research like my own possible. May this commitment continue. I would also like to thank Sam Elworthy for steering this project and Ginny Sullivan for her sympathetic editing, along with Jane McRae for her proofreading, Tim Nolan for his maps, and all the staff of Auckland University Press.

Michael Belgrave

ANZAC Day, 2017

CHAPTER ONE

Stalemate

1864

I N LATE MARCH 1864, REWI MANIAPOTO OF NGTI MANIAPOTO AND RAUKAWA was one of the leaders of a small band of fighters who were caught defending an ill-chosen and poorly prepared position at rkau. They faced well-trained, better armed and more experienced troops led by Duncan Cameron, one of the British Empires most respected generals. The defenders possessed shotguns and some rifles but were also armed with pounamu and whalebone mere and taiaha. They had little ammunition, resorting to using peach stones and wooden projectiles for bullets. With little food or water, outnumbered six to one, these supporters of the Kngitanga (the Mori King movement) held out for three days, suffering heavy casualities when breaking through the lines that encircled them. In the escape, Ahumai Te Paerata of Raukawa took four hits to her body and one that blew away her thumb. She escaped with one of her brothers, but her father and another brother died in the siege, as did around 150 of the defenders. Some had been protecting their homes, such as those from the related tribes of Ngti Maniapoto, Ngti Apakura and Raukawa. Others had come from much further afield, Ngti Whare and Ngi Thoe from the Urewera, and Ngti Porou from the East Coast.

Heroism, defiance and defeat soon became enshrined in the mythology of the countrys origins, defining rkau as a place of sadness and glory, the spot where the Kingites made their last hopeless stand for independence, holding heroically to nationalism and a broken cause, as the wars most important early historian, James Cowan, put it.

Rewis last stand, as the battle was soon labelled, marked the end of the Waikato War. Over a million acres of confiscated land in the Waikato was now available for settler towns and farms, and hundreds of thousands more quickly fell into the hands of Auckland speculators through land purchases. Camerons troops moved on, to Tauranga and the East Coast and back to Taranaki where the war had begun. Historians, like camp followers, have moved with them, finding new heroes or villains in later war leaders, in Kereopa Te Rau and Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Truki, in Ttokowaru and in the passive resisters to military aggression, Te Whiti-o-Rongomai, Tohu Kkahi and Rua Knana.

For the Waikato people, rkau signified the end of one form of resistance and the beginning of another. The defeat expelled them and their allies southward to beyond the points of navigation of the Waikato and Waip rivers. Led by Twhiao, the second Mori King, they retreated into an armed exile in the Rohe Ptae, the King Country, in the midst of their Tainui relations and allies, Ngti Maniapoto, Ngti Apakura, Ngti Twharetoa and the iwi of the upper Whanganui. It was a massive area from the Pniu in the north to the Whanganui in the south, and from Taup west to the sea. From 1865 to 1886, Mori and Pkeh recognised the aukati the border between the Queens authority and the Kings. South of the aukati, the Kings people were contained, but they remained an independent state beyond the control of the New Zealand governments police and land surveyors, tax collectors and railway builders. Europeans travelled into the area at their own risk, and a few met violent deaths. Their killers, in a constant reminder of the limits of colonial power, remained at large within the Kings court and defiantly beyond the grasp of colonial law. The Rohe Ptae also became the refuge for Mori who had taken up armed resistance to the Crown, most notably Te Kooti from 1872. For years, he sat audaciously beyond the legal authority of the Queen and the vengeance of those communities he had ravaged on the East Coast.

Next page