POLITICAL GASTRONOMY

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series editors: Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown,

Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary,

and early national history and culture, Early American Studies

reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways.

Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on

the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in

partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series

is available from the publisher.

POLITICAL

GASTRONOMY

Food and Authority

in the English Atlantic World

Michael A. LaCombe

Copyright 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for

purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book

may be reproduced in any form by any means without

written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data LaCombe, Michael A.

Political gastronomy : food and authority in the English Atlantic world / Michael A. LaCombe. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4418-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. North AmericaHistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775. 2. FoodPolitical aspectsNorth AmericaHistory. 3. Great BritainColoniesAmericaHistory17th century. 4. Great BritainColoniesAmericaSocial conditions. 5. ColonistsNorth AmericaAttitudes 6. Indians of North AmericaFoodPolitical aspects. 7. Indians of North AmericaFirst contact with Europeans. I. Title. II. Series: Early American studies

E46.L33 2012

973.2dc23

2011045999

For Christa, Sophia, and Vivian

The table constitutes a kind of tie between the bargainer and the bargained-with, and makes the diners more willing to receive certain impressions, to submit to certain influences: from this is born political gastronomy. Meals have become a means of governing, and the fate of whole peoples is decided at a banquet.

Jean Anthlme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste, or, Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, trans. M. F. K. Fisher

Contents

Introduction

Hungry, wet, and weary, a small group of English men rowed into the Carolina Sounds in the summer of 1584. They had arrived less than a month earlier, sent to explore the region and make contact with its native population. After a few tentative encounters with Carolina Algonquians, the English party decided to leave the safety of their ships and set out for the village of Roanoke.

As they watched the English approach, Roanokes Algonquian inhabitants displayed the same mixture of curiosity and apprehension as their approaching guests. Most of the small group standing on shore were women, who had been cooking, tending fires, and minding children until they saw the English approaching. Among them was a woman whose clothing, hair, and bearing distinguished her from the rest. The wife of Granganimeo, a prominent man, and sister-in-law of Wingina, the Carolina Algonquians overall leader, she had visited the English ships a few days before with her husband and children. In her husbands absence, she arranged a warm welcome for these uninvited but important guests: a fire, a bath, a meal, and a place to sleep.

Interactions like this one were not uncommon in the early period, and it was no accident that food lay at the center of each. Granganimeos wife believed that a woman of her station was obligated to offer hospitality, and her guests shared these assumptions. This meant that as the English travelers sat and rested, warmed themselves, and ate (gesturing for more helpings of various dishes, smiling and nodding politely to their hostess, and offering comments to each other on the meal), they were also taking part in a form of communication. Everyone present at this meal knew that it was an important occasion and that meanings were being shared along with foods, and everyone conducted him- or herself accordingly. However vast the gulf of culture, religion, history, and technology that separated English from Indians, a table brought them surprisingly close together.

Political Gastronomy explores what food meantand how food meantto these men and women and many others like them. Food is as ubiquitous in the written accounts of early America as the labor associated with it was in daily life. When Indians and English produced food, exchanged it, ate it, or described their experiences, they conveyed dense and interlaced messages about status, gender, civility, diplomacy, and authority.

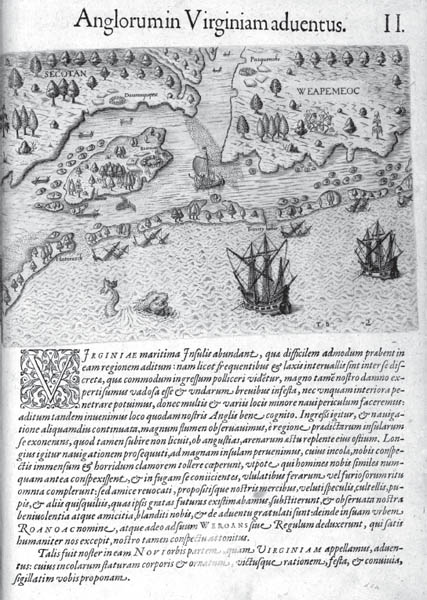

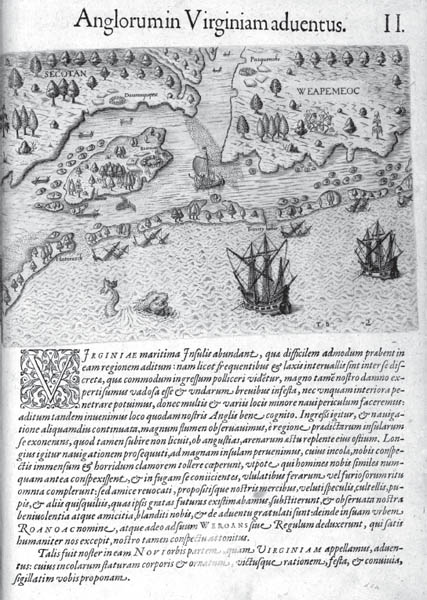

Figure 1. This engraving, titled The arrival of the Englishemen in Virginia, was prepared by the workshop of Theodor de Bry to accompany the 1590 edition of Thomas Harriots A briefe and true report. Roanoke Island is shown surrounded by canoes and a fishing weir. On the island itself, the village of Roanoke is surrounded by fields of maize, as are the two other native villages depicted. In the forests of Roanoke Island, Algonquian hunters are shown pursuing deer, while on the mainland grapevines of the sort Arthur Barlowe described offer another image of plenty. Courtesy Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

The 1584 Roanoke voyage was intended to find a likely site for an eventual settlement, and in his manuscript account of the voyage Arthur Barlowe claimed success. Reporting to the voyages backers, who included the influential young courtier Sir Walter Ralegh, Barlowe described islands so full of grapes, as the very beating, and surge of the Sea overflowed them, of which we founde such plentie, as well there, as in all places else, both on the sande, and on the greene soile on the hils, as in the plaines, as well on every little shrubbe, as also climing towardes the toppes of the high Cedars, that I thinke in all the world the like aboundance is not to be founde. The forests were, Barlowe went on, full of Deere, Conies, Hares, and Fowle, even in the middest of Summer, in incredible aboundance. Tangled vines heavy with fruit and forests teeming with game offered a tempting image of opportunity: a fertile landscape not fully exploited by its native population where English travelers and potential settlers might feed themselves with minimal labor.

Barlowe also hoped to make contact with the native population of the Sounds, and on the third day of Barlowes explorations, a group of three Carolina Algonquians paddled ashore within sight of the English ships. One of this group came along the shoare side towards us and walked up and downe uppon the point of the lande next unto us, which the English understood as an invitation for a small party to row ashore to meet him.