Hammer and Hoe

1990 The University of North Carolina Press

Preface to the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Edition 2015 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

ISBN 978-1-4696-2548-5

ISBN 978-1-4696-2549-2

The Library of Congress has cataloged the original edition of this book as follows:

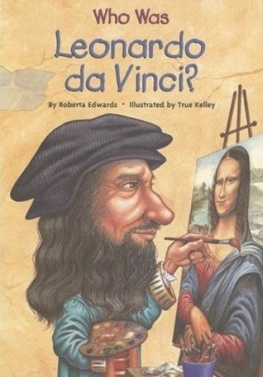

Kelley, Robin D. G.

Hammer and hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression /

by Robin D. G. Kelley.

p. cm.(The Fred W. Morrison series in Southern studies)

Includes bibliographical references.

I. CommunismAlabamaHistory20th century. 2. Communists

AlabamaHistory20th century. 3. Depressions1929Alabama.

I. Title. II. Series.

HX9I.A2K45 1990

324.2761'075'09042dc20 90-50018

CIP

Dedicated to the young people of Ferguson, St. Louis, Baltimore, Miami, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Oakland, Gaza and the West Bank, Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Dakar, Cairo, Ayotzinapa and Mexico City, Santiago, Athens, Lisbon, Madrid, and elsewhere, fighting for justice, democracy, peace, and an end to human misery.

Contents

Illustrations

Black convict laborers, Banner Mine, Alabama

Al Murphy

Hosea Hudson

Sharecropping family, near Eutaw, Alabama

Lemon Johnson, SCU secretary of Hope Hull, Alabama, local

Company suburb

Clyde Johnson

Meat for the Buzzards!

Anti-Communist handbill distributed by the Ku Klux Klan

Fight Lynch Terror!

Smash the Barriers!

District 17 secretary Robert Fowler Hall

Sit-down strike, American Casting Company, Birmingham, 1937

Share Croppers Union membership card

Eugene Bull Connor, Birmingham city commissioner

League of Young Southerners

Ethel Lee Goodman

Segregated audience in Montgomery awaits Henry Wallace, 1948

Preface

Ain't no foreign country in the world foreign as Alabama to a New Yorker. They know all about England, maybe, France, never met one who knew Bama.

Anonymous black Communist, 1945

After spending several years hobnobbing with European, Asian, and Soviet dignitaries of the Third International, Daily Worker correspondent Joseph North made a most unforgettable journey to, of all places, Chambers County, Alabama. Traveling surreptitiously with a black Birmingham Communist as his escort, North reached his destinationthe tumbledown shack of a sharecropper comradein the wee hours of the night. The dark figure who greeted the two men had read the Worker for years; solid and reliable, he was respected by his folk here, who regarded him as a man with answers. The sharecropper was an elder in the Zion [A.] M.E. Church, who trusts God but keeps his powder dry; reads his Bible every night, can quote from the Book of Daniel and the Book of Job... and he's been studying the Stalin book on the nation question.

Although North's visit took place in 1945, on the eve of the Alabama Party's collapse, the sharecropper comrade he describes above epitomized the complex, seemingly contradictory radical legacy the Party left behind. Built from scratch by working people without a Euro-American left-wing tradition, the Alabama Communist Party was enveloped by the cultures and ideas of its constituency. Composed largely of poor blacks, most of whom were semiliterate and devoutly religious, the Alabama cadre also drew a small circle of white folkswhose ranks swelled or diminished over timeranging from ex-Klansmen to former Wobblies, unemployed male industrial workers to iconoclastic youth, restless housewives to renegade liberals.

These unlikely radicals, their milieu, and the movement they created make up the central subjects of this book. Heeding Victoria de Grazia's appeal to historians of the American Left for a social history of politics, I have tried to construct a narrative that examines Communist political opposition through the lenses of social and cultural history, paying particular attention to the worlds from which these radicals came, the worlds in which they lived, and the imaginary worlds they sought to build. I pluralize worlds to emphasize the myriad individual and collective differences within the Alabama Communist movement. Those assembled under the red

And Alabama Communists had titanic boundaries to exceed. More than in the Northeast and Midwest, the regional incubators of American Communism, race pervaded virtually every aspect of Southern society. The relations between industrial labor and capital, and landlords and tenants, were clouded by divisions based on skin color. On the surface, at least, it seemed that there existed two separate racial communities in the segregated South that only intersected in the world of work or at the marketplace. Sharp class distinctions endured within both black and white communities, but racism tended to veil, and at times arrest, intraracial class conflict as well as interracial working-class unity. Alabama Party leaders could not escape the prevalence of race, despite their unambiguous emphasis on class-based politics. Indeed, during its first five years in Alabama, the CP inevitably evolved into a race organization, a working-class alternative to the NAACP. As Nell Painter observed, the rank-and-file folk made the Party their own. In Alabama in the 1930s, the CP was a southern, working-class black organization.

The homegrown radicalism that had germinated in poor black communities and among tiny circles of white rebels remained deep underground. Alabama Communists did not have much choice. Their challenge to racism and to the status quo prompted a wave of repression one might think inconceivable in a democratic country. The extent and character of anti-radical repression in the South constitute a crucial part of our story. When we ponder Werner Sombart's question, Why is there no socialism in the United States? in light of the South, violence and lawlessness loom large. The fact is, the CP and its auxiliaries in Alabama did have a considerable following, some of whom devoured Marxist literature and dreamed of a socialist world. But to be a Communist, an ILD member, or an SCU militant was to face the possibility of imprisonment, beatings, kidnapping, and even death. And yet the Party survived, and at times thrived, in this thoroughly racist, racially divided, and repressive social world.

Indeed, most scholars have underestimated the Southern Left and have underrated the role violence played in quashing radical movements. Religious fundamentalism, white racism, black ignorance or indifference, the Communists presumed insensitivity to Southern culture, their advocacy of black self-determination during the early 1930s, and an overall lack of class consciousness are all oft-cited explanations for the Party's failure to attract Southern workers. The experiences of Alabama Communists, however, suggest that racial divisions were far more fluid and Southern working-class consciousness far more complex than most historians have realized. The African-Americans who made up the Alabama radical movement experienced and opposed race and class oppression as a totality. The Party and its various auxiliaries served as vehicles for black working-class opposition on a variety of different levels ranging from antiracist activities to intraracial class conflict. Furthermore, the CP attracted some openly bigoted whites despite its militant antiracist slogans. The Party also drew women whose efforts to overcome gender-defined limitations proved more decisive to their radicalization than did either race or class issues.

Next page