David Graeber - The Democracy Project

Here you can read online David Graeber - The Democracy Project full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: ePubLibre, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

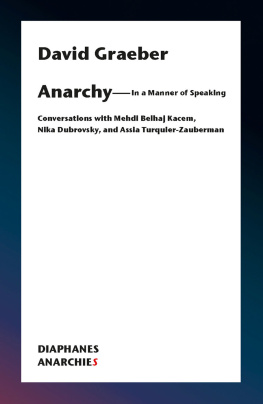

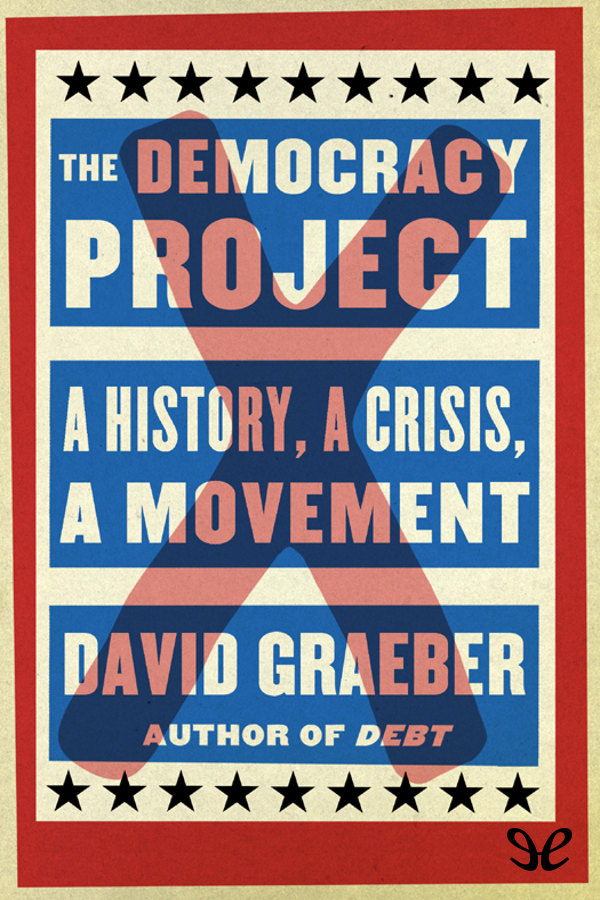

- Book:The Democracy Project

- Author:

- Publisher:ePubLibre

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Democracy Project: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Democracy Project" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Democracy Project — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Democracy Project" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

to my father

Democracy has been the American religion since before the Revolution from New England town halls to the multicultural democracy of Atlantic pirate ships. But can our current political system, one that seems responsive only to the wealthiest among us and leaves most Americans feeling disengaged, voiceless, and disenfranchised, really be called democratic? And if the tools of our democracy are not working to solve the rising crises we face, how can we average citizens make change happen?

The Democracy Project tells the story of the resilience of the democratic spirit and the adaptability of the democratic idea. It offers a fresh take on vital history and an impassioned argument that radical democracy is, more than ever, our best hope.

David Graeber

A history, a crisis, a movement

ePub r1.0

marianico_elcorto11.12.13

Ttulo original: The Democracy Project

David Graeber, 2013

Diseo de portada: Jamie Keenan

Editor digital: marianico_elcorto

ePub base r1.0

DAVID GRAEBER. Born 12 February 1961, is an American anthropologist, author, anarchist and activist who is currently Professor of Anthropology at the London School of Economics.

Specialising in theories of value and social theory, he was an assistant professor and associate professor of anthropology at Yale University from 1998 to 2007, although Yale controversially declined to rehire him. From Yale, he went on to become a Reader in Social Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London from Fall 2007 to Summer 2013.

Graeber has been involved in social and political activism, including the protests against the 3rd Summit of the Americas in Quebec City in 2001 and the World Economic Forum in New York City in 2002. He is also a leading figure in the Occupy Wall Street movement.

On April 26, 2012, about thirty activists from Occupy Wall Street gathered on the steps of New Yorks Federal Hall, across the street from the Stock Exchange.

For more than a month, we had been trying to reestablish a foothold in lower Manhattan to replace the camp wed been evicted from six months earlier at Zuccotti Park. Even if we werent able to establish a new camp, we were hoping to at least find some place we could hold regular assemblies, and set up our library and kitchens. The great advantage of Zuccotti Park was that it was a place where anyone interested in what we were doing knew they could always come to find us, to learn about upcoming actions or just talk politics; now the lack of such a place was causing endless problems. The city authorities, however, had decided that we would never have another Zuccotti. Wherever we found a spot we could legally set up shop, they simply changed the laws and drove us off. When we tried to establish ourselves in Union Square, city authorities changed park regulations. When a band of occupiers started sleeping on the sidewalk on Wall Street itself, relying on a judicial decision that explicitly said citizens had a right to sleep on the street in New York as a form of political protest, the city deemed that part of lower Manhattan a special security zone in which the law did not apply.

Finally, we settled on the Federal Hall steps, a broad marble staircase leading up to a statue of George Washington, guarding the door to the building in which the Bill of Rights had been signed 223 years before. The steps were not under city jurisdiction; they were federal land, under the administration of the National Park Service, and representatives of the U.S. Park Police cognizant, perhaps, that the entire space was considered a monument to civil liberties had told us they had no objections to our occupying the steps, as long as no one actually slept there. The steps were wide enough that they could easily accommodate a couple of hundred people, and at first, about that many occupiers showed up. But before long, the city had moved in and convinced the parks people to let them effectively take over: theyd erected steel barriers around the perimeter, and others that divided the steps themselves into two compartments. We quickly came to refer to them as the freedom cages. A SWAT team was positioned by the entrance, and a white-shirted police commander carefully monitored everyone who tried to enter, informing them that for safety reasons no more than twenty people were allowed in either cage at any time. Nonetheless, a determined handful persevered. They kept up a twenty-four-hour presence, taking shifts, organizing teach-ins during the day, engaging in impromptu debates with bored Wall Street traders who wandered over during breaks, and keeping vigil on the marble stairs at night. Soon large signs were banned. Then anything made of cardboard. Then came the random arrests. The police commander wanted to make clear to us that, even if he couldnt arrest all of us, he could certainly arrest any one of us, for pretty much any reason, at any time. That day alone I had seen one activist shackled and led off for a noise violation while chanting slogans, and another, an Iraq war veteran, booked on public obscenity charges for using four-letter words while making a speech. Perhaps it was because wed advertised the event as a speak-out. The officer in charge seemed to be making a point: even at the very birthplace of the First Amendment, he still had the power to arrest us just for engaging in political speech.

A friend of mine named Lopi, famous for attending marches on a giant tricycle emblazoned with a colorful placard that read Jubilee! had organized the event, billing it as Speak Out of Grievances against Wall Street: A Peaceable Assembly on the steps of the Federal Hall Memorial Building, the birthplace of the Bill of Rights which is currently under lock down from the army of the 1%. Myself, Ive never been much of a rabble-rouser. During the entire time Id been involved in Occupy, Id never once made a speech. So I was hoping to be there mainly as a witness, to provide moral and organizational support. For much of the first half hour of the event, as one occupier after another moved to the front of the cage, before an impromptu collection of video cameras on the sidewalk, to talk about war, ecological devastation, the corruption of government, I lingered on the margins, trying to chat up the police.

So youre part of a SWAT team, I said to one grim-faced young man guarding the entrance to the cages, a large assault rifle at his side. Now, what does that stand for, SWAT? Special Weapons

and Tactics, he said quickly, before I would have any chance to get out the original name for the unit, which was Special Weapons Assault Team.

I see. So Im curious: what sort of special weapons do your commanders think might be required to deal with thirty unarmed citizens engaging in peaceable assembly on the federal steps?

Its just a precaution, he replied uncomfortably.

Id already passed up two invitations to speak, but Lopi was persistent, so eventually, I figured Id better say something, however brief. So I took my place in front of the cameras, glanced up at George Washington gazing at the sky over the New York Stock Exchange, and started improvising.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Democracy Project»

Look at similar books to The Democracy Project. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Democracy Project and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.