Also by David Graeber

Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value

The False Coin of Our Own Dreams

Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology

Lost People

Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar

Possibilities

Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire

Direct Action

An Ethnography

Debt

The First 5,000 Years

Revolutions in Reverse

Essays on Politics, Violence, Art, and Imagination

The Democracy Project

A History, A Crisis, A Movement

THE UTOPIA OF RULES

Copyright 2015 by David Graeber

First Melville House printing: February 2015

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint a panel from Kultur Dokuments, which originally appeared in Anarchy Comics #2 and was collected in Anarchy Comics: The Complete Collection, edited by Jay Kinney and published by PM Press in 2012.

Copyright 1979 and 2013 by Jay Kinney and Paul Mavrides.

The following chapters originally appeared, in somewhat different form, in the following publications:

Dead Zones of the Imagination: An Essay on Structural Stupidity as Dead Zones of the Imagination: On Violence, Bureaucracy, and Interpretive Labor. The 2006 Malinowski Memorial Lecture, in HAU: The Journal of Ethnographic Theory, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2012.

Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit, in The Baffler, No. 19, 2012.

On Batman and the Problem of Constituent Power as Super Position, in The New Inquiry, October 8, 2012.

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com / facebook.com/mhpbooks / @melvillehouse

ISBN: 978-1-61219-374-8 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1-61219-448-6 (paperback; export edition)

ISBN: 978-1-61219-375-5 (ebook)

Design by Adly Elewa

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

Contents

Introduction

The Iron Law of Liberalism and the Era of Total Bureaucratization

1 Dead Zones of the Imagination

An Essay on Structural Stupidity

Appendix

On Batman and the Problem of Constituent Power

Introduction

The Iron Law of Liberalism and the Era of Total Bureaucratization

Nowadays, nobody talks much about bureaucracy. But in the middle of the last century, particularly in the late sixties and early seventies, the word was everywhere. There were sociological tomes with grandiose titles like A General Theory of Bureaucracy, There were Kafkaesque novels, and satirical films. Everyone seemed to feel that the foibles and absurdities of bureaucratic life and bureaucratic procedures were one of the defining features of modern existence, and as such, eminently worth discussing. But since the seventies, there has been a peculiar falling off.

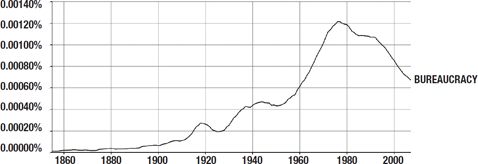

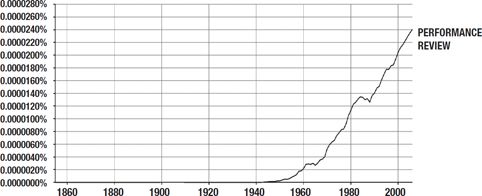

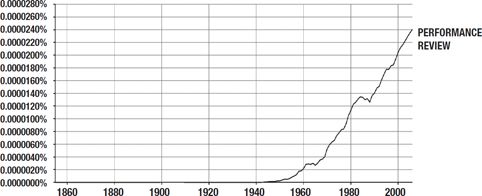

Consider, for example, the following table, which diagrams how frequently the word bureaucracy appears in books written in English over the last century and a half. A subject of only moderate interest until the postwar period, it shoots into prominence starting in the fifties and then, after a pinnacle in 1973, begins a slow but inexorable decline.

Why? Well, one obvious reason is that weve just become accustomed to it. Bureaucracy has become the water in which we swim. Now lets imagine another graph, one that simply documented the average number of hours per year a typical Americanor a Briton, or an inhabitant of Thailandspent filling out forms or otherwise fulfilling purely bureaucratic obligations. (Needless to say, the overwhelming majority of these obligations no longer involve actual, physical paper.) This graph would almost certainly show a line much like the one in the first grapha slow climb until 1973. But here the two graphs would divergerather than falling back, the line would continue to climb; if anything, it would do so more precipitously, tracking how, in the late twentieth century, middle-class citizens spent ever more hours struggling with phone trees and web interfaces, while the less fortunate spent ever more hours of their day trying to jump through the increasingly elaborate hoops required to gain access to dwindling social services.

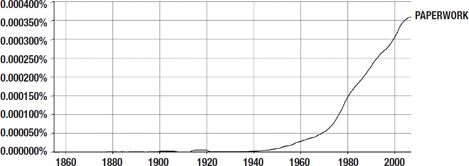

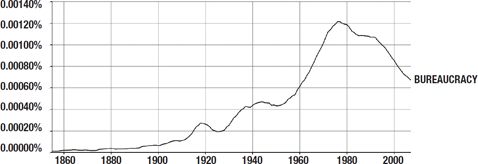

I imagine such a graph would look something like this:

This is not a graph of hours spent on paperwork, just of how often the word paperwork has been used in English-language books. But absent time machines that could allow us to carry out a more direct investigation, this is about as close as were likely to get.

By the way, most similar paperwork-related terms yield almost identical results:

The essays assembled in this volume are all, in one way or another, about this disparity. We no longer like to think about bureaucracy, yet it informs every aspect of our existence. Its as if, as a planetary civilization, we have decided to clap our hands over our ears and start humming whenever the topic comes up. Insofar as we are even willing to discuss it, its still in the terms popular in the sixties and early seventies. The social movements of the sixties were, on the whole, left-wing in inspiration, but they were also rebellions against bureaucracy, or, to put it more accurately, rebellions against the bureaucratic mindset, against the soul-destroying conformity of the postwar welfare states. In the face of the gray functionaries of both state-capitalist and state-socialist regimes, sixties rebels stood for individual expression and spontaneous conviviality, and against (rules and regulations, who needs them?) every form of social control.

With the collapse of the old welfare states, all this has come to seem decidedly quaint. As the language of antibureaucratic individualism has been adopted, with increasing ferocity, by the Right, which insists on market solutions to every social problem, the mainstream Left has increasingly reduced itself to fighting a kind of pathetic rearguard action, trying to salvage remnants of the old welfare state: it has acquiesced withoften even spearheadedattempts to make government efforts more efficient through the partial privatization of services and the incorporation of ever-more market principles, market incentives, and market-based accountability processes into the structure of the bureaucracy itself.

The result is a political catastrophe. Theres really no other way to put it. What is presented as the moderate Left solution to any social problemsand radical left solutions are, almost everywhere now, ruled out tout courthas invariably come to be some nightmare fusion of the worst elements of bureaucracy and the worst elements of capitalism. Its as if someone had consciously tried to create the least appealing possible political position. It is a testimony to the genuine lingering power of leftist ideals that anyone would even consider voting for a party that promoted this sort of thingbecause surely, if they do, its not because they actually think these are good policies, but because these are the only policies anyone who identifies themselves as left-of-center is allowed to set forth.