Fred C. Abrahams

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Abrahams, Fred.

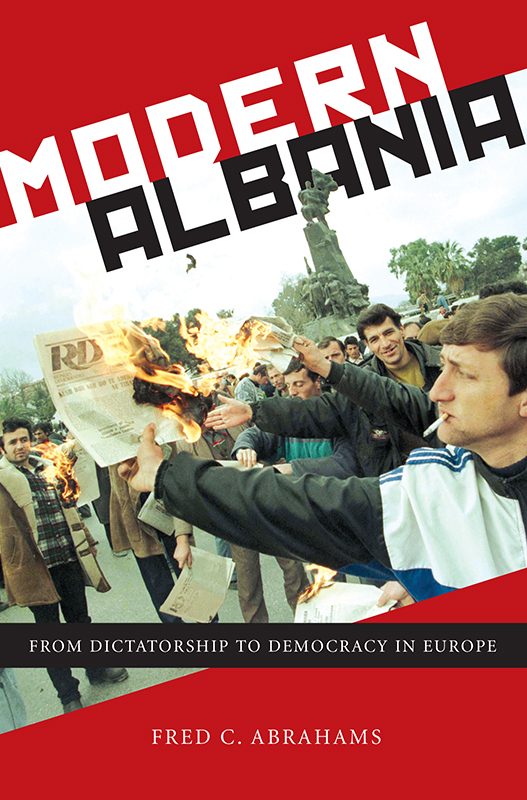

Modern Albania : from dictatorship to democracy in Europe / Fred C. Abrahams.

pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8147-0511-7 (cl : alk. paper)

1. AlbaniaPolitics and government1990 2. Post-communismAlbania. 3. DemocracyAlbania. I. Title.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

To my parents, Carole and David, for the roots and wings.

For four decades after World War Two, tiny Albania was hermetically sealed. The Stalinist dictator, Enver Hoxha, banned religion, private property, and decadent music such as the Beatles. Secret police arrested critics and border guards shot people who tried to flee. But as communism crumbled across the Eastern Bloc, the regime loosened its grip. Pressed by demonstrations and poverty, in late 1990 the communists allowed other parties to exist. In early 1992, more than two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a democratically elected government came to power and started to bring Albania in from the cold.

Albania made a rapid switch. It transformed from a country with sealed borders to a smugglers dream, from the worlds only officially atheist state to a playground for religions, from a land with no private cars to a jumble of belching cars, buses, and trucks. Albania flipped from a country of harsh, top-down repression to a vibrant state where most anything goes.

This book describes that dramatic jump. It tells the inside story of Albanias democratic awakening, the so-called revolution, when rigid Stalinism collapsed and wild pluralism stormed in. And it explains the effort since then to build a more just and tolerant society after decades of labor camps, thought police, and one-party rule.

The participants in this drama drive the tale: a paranoid dictator, an ambitious doctor, a scheming economist, an urban artist. Over two decades, I interviewed most of the influential Albanians in the countrys political life and many of the foreigners who played a role. They describe the first student protests, the last Politburo meetings, and the struggle to build democracy after dictatorship. To supplement their accounts, I cite articles from the Albanian press and previously secret records from Albania and the United States, mostly from the State Department and CIA.

I also enjoyed a front-row seat. I first went to Albania in 1993 and worked there for one year at a media training center, watching the wobbly first steps of democracy. I then covered the country for Human Rights Watch and saw the resilience of one-party rule, the pull of dictatorship, and in 1997 the crash of massive pyramid schemes, when defrauded people torched city halls and looted military depots. The next year, war erupted in neighboring Kosovo, culminating in NATOs air assault on Serbian and Yugoslav forces. Albania offered a staging ground and supply route for the ragtag Albanian insurgency, and later a grave site for its victims. After 2001, I observed mostly Muslim Albania serve as a devoted ally of the United States. The government detained and helped render terrorist suspects, accepted released Guantanamo prisoners, and sent troops to Afghanistan and Iraq. Albania is probably the only country outside the United States with a statue of George W. Bush.

During this time, I watched the United States and other Western democracies repeatedly make shortsighted decisions that stymied Albanias transition. For many years, the U.S. and West European governments supported an authoritarian or corrupt Albanian leader for the sake of stability in the Balkans and, later, Albanias cooperation in the war on terror. These governments frequently backed an individual more than the countrys institutions; for this, Albania is today paying a significant price.

Through it all, I had the opportunity to mingle with Albanias elite. I watched former political prisoners join the government and government ministers go to jail. I saw foreigners who loved Albania get declared persona non grata while swindlers won business contracts and the highest state praise. I have been called a Communist, a CIA agent, pro-Albanian, anti-Albanian, pro-Greek, anti-Greek, pro-Serb, anti-Serb, and by one journalist, a whimsical boy with an earring and short pants. But above all, I have been privileged to peer behind the curtain of a society that is for many outsiders opaque.

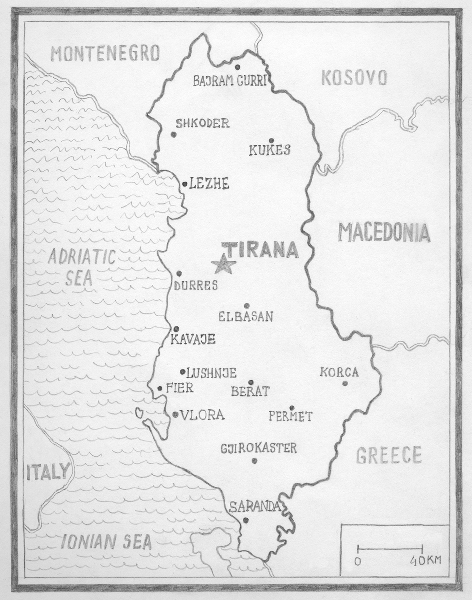

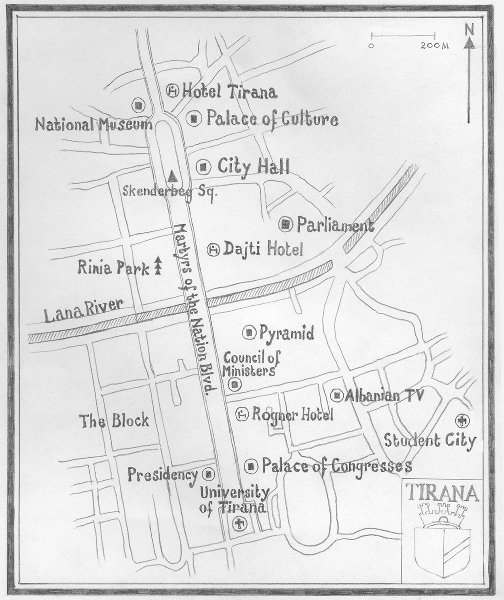

The book has limitations. First, it focuses on the capital, Tirana, and the boulevard that forms its spine. Second, it deals primarily with men, who dominate Albanias public life. Third, it mostly explores Albanias relationship with the United States, with less attention on other countries. With these in mind, I hope the book helps dispel myths, spark debate, and shed light on a tiny country in Europe going through a remarkable time.

Fred Abrahams

New York City

On the Boulevard

The dry, rocky mountains of Montenegro drew near as the plane decended from the north. The high peaks of Albania rose to the left, flashing their fangs to the sky. The jagged teeth settled into deep valleys and dense forests that held the highlanders I had read about and would soon meet for myself.

The mountains got shorter and rounder as the plane slid south. The gray rock ran down the countrys eastern length like a spine. Albania is a small country, a saying goes, but it would grow ten times if it were ironed flat. On the western side, the ridges melted into barren hills and farm land, which slid in brown and gray to the Adriatic Sea. Albania is like an amphitheater, I thought, with high seats in the mountains offering views of the coastal plain and greenish sea. Except for the soft water, the country looked harsh. It resembled a fortress or massive crag, and this geography, I learned, has shaped the peoples lives. Oft invaded and overrun, Albanians honor guests but view outsiders with a leery eye.

The fields looked choppy and parched. Gray flecks dotted the land like acne on a teenage face: the concrete military bunkers built during communism on almost every farm, field, and mountain to repel invasion and, more important, to instill fear of outside attack. The pillboxes proved difficult to destroy and for years served as food stands and sometimes as homes for the poor.