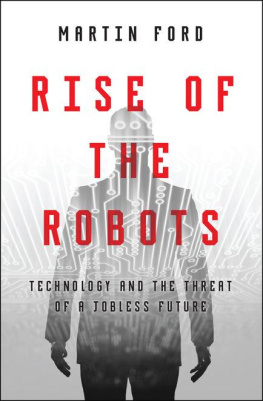

More Praise for The Rise of the Robots

A fascinating journey into the near future world of unemployment. Ford issues a stark warning that automation in the form of robotics is moving beyond the menial jobs to put the rest of us out of work. Read it now before it is too late.

Noel Sharkey, Emeritus Professor of Artificial Intelligence

and Robotics, University of Sheffield

The real existential threat of AI is not biological extinction but philosophical identity, as even (or perhaps especially) humanitys greatest thinkers have to come to terms with the fact that their abilities can be not only understood, but replicated in machines. Martin Ford addresses this new reality with exceptional insight and clarity. He doesnt shy away from recognizing the many positive outcomes of intelligent technology, while exposing the negative consequences of the very real impacts our society is already experiencing.

Dr. Joanna Bryson, Department of Computer Science, University of Bath

Finally this important topic is being addressed by someone who has both a grasp on the economic issues and a grounded understanding of what AI and robotics technology is really capable of now and in the near future. This is combined with a clarity of explanation that can help anyone understand the significant societal changes that will soon be upon us.

Dr. Nick Hawes, Reader in Autonomous Intelligent Robotics,

University of Birmingham

Lucid, comprehensive and unafraid to grapple fairly with those who dispute Fords basic thesis, The Rise of the Robots is an indispensable contribution to a long-running argument.

Los Angeles Times

As Martin Ford documents in The Rise of the Robots, the job-eating maw of technology now threatens even the nimblest and most expensively educated the human consequences of robotization are already upon us, and skillfully chronicled here.

New York Times Book Review

An alarming new book.

Esquire

A careful and courageous examination of automation and its possible impact on society.

Kirkus Reviews

ALSO BY Martin Ford:

The Lights in the Tunnel: Automation, Accelerating Technology and the Economy of the Future

The Rise of the Robots

Technology and the Threat of Mass Unemployment

Martin Ford

A Oneworld Book

First published in Great Britain by Oneworld Publications, 2015

First published in the United States by Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group

This ebook edition published by Oneworld Publications, 2015.

Copyright Martin Ford 2015

The moral right of Martin Ford to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-749-1

eISBN 978-1-78074-750-7

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books,

special offers, and exclusive content from

Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

To Tristan, Colin, Elaine, and Xiaoxiao

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Sometime during the 1960s, the Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman was consulting with the government of a developing Asian nation. Friedman was taken to a large-scale public works project, where he was surprised to see large numbers of workers wielding shovels, but very few bulldozers, tractors, or other heavy earth-moving equipment. When asked about this, the government official in charge explained that the project was intended as a jobs program. Friedmans caustic reply has become famous: So then, why not give the workers spoons instead of shovels?

Friedmans remark captures the skepticismand often outright derisionexpressed by economists confronting fears about the prospect of machines destroying jobs and creating long-term unemployment. Historically, that skepticism appears to be well-founded. In the West, especially during the twentieth century, advancing technology has consistently driven us toward a more prosperous society.

There have certainly been hiccupsand indeed major disruptionsalong the way. The mechanization of agriculture vaporized millions of jobs and drove crowds of unemployed farmhands into cities in search of factory work. Later, automation and globalization pushed workers out of the manufacturing sector and into new service jobs. Short-term unemployment was often a problem during these transitions, but it never became systemic or permanent. New jobs were created and dispossessed workers found new opportunities.

Whats more, those new jobs were often better than earlier counterparts, requiring upgraded skills and offering better wages. At no time was this more true than in the two and a half decades following World War II. This golden age for the West was characterized by a seemingly perfect symbiosis between rapid technological progress and the welfare of the workforce. As the machines used in production improved, the productivity of the workers operating those machines likewise increased, making them more valuable and allowing them to demand higher wages. Throughout the postwar period, advancing technology deposited money directly into the pockets of average workers as their wages rose in tandem with soaring productivity. Those workers, in turn, went out and spent their ever-increasing incomes, further driving demand for the products and services they were producing.

As that virtuous feedback loop powered developed economies forward, the profession of economics was enjoying its own golden age. It was during the same period that towering figures like Paul Samuelson worked to transform economics into a science with a strong mathematical foundation. Economics gradually came to be almost completely dominated by sophisticated quantitative and statistical techniques, and economists began to build the complex mathematical models that still constitute the fields intellectual basis. As the postwar economists did their work, it would have been natural for them to look at the thriving economy around them and assume that it was normal: that it was the way an economy was supposed to workand would always work.

In his 2005 book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Succeed or Fail, Jared Diamond tells the story of agriculture in Australia. In the nineteenth century, when Europeans first colonized Australia, they found a relatively lush, green landscape. Like economists in the 1950s, the Australian settlers assumed that what they were seeing was normal, and that the conditions they observed would continue indefinitely. They invested heavily in developing farms and ranches on this seemingly fertile land.

Within a decade or two, however, reality struck. The farmers found that the overall climate was actually far more arid than they were initially led to believe. They had simply had the good fortune (or perhaps misfortune) to arrive during a climactic Goldilocks perioda sweet spot when everything happened to be just right for agriculture. Today in Australia, you can find the remnants of those ill-fated early investments: abandoned farm houses in the middle of what is essentially a desert.

There are good reasons to believe that the economic Goldilocks period has likewise come to an end for many developed nations. In the US, the symbiotic relationship between increasing productivity and rising wages began to dissolve in the 1970s. As of 2013, a typical production or nonsupervisory worker earned about 13 percent less than in 1973 (after adjusting for inflation), even as productivity rose by 107 percent and the costs of housing, education, and healthcare have soared.

Next page