RACE IN MIND

RACE IN MIND

Critical Essays

PAUL SPICKARD

with Jeffrey Moniz and Ingrid Dineen-Wimberly

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

www.undpress.nd.edu

Copyright 2016 by the University of Notre Dame

All Rights Reserved

Published in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spickard, Paul R., 1950 Moniz, Jeffrey, Dineen-Wimberl, Ingrid

Race in mind : critical essays / Paul Spickard ;

with Jeffrey Moniz and Ingrid Dineen-Wimberly.

Notre Dame, Ind. : University of Notre Dame Press, [2015]

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780268041489 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 0268041482 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Race. Ethnicity. Race relations. Multiculturalism.

HT1521.S624 2015

305.8dc23

2015032735

ISBN 9780268182007

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at .

In memory of

Win Jordan

Contents

FIGURES

TABLES

As this manuscript goes to press, I find I owe debts of gratitude beyond my capacity to repay to two people. Patrick Miller has been a fellow traveler on many, many adventures over the years. He has never failed to retain his good humor while doing his best to restrain some of my rhetorical excesses. Reginald Daniels name appears often in the notes to the pages that follow, but he deserves special mention, for he has been a boon companion and is the single person to whom my thinking about race owes the greatest debt.

At the University of Notre Dame Press, Chuck Van Hof showed enthusiasm for the project from the start. He and his colleagues Stephen Little, Rebecca DeBoer, and Sheila Berg have done a more than professional job of editing. I am grateful for both. Among those he recruited to help me make this book better are Roger Daniels, the dean of American immigration historians, and Maria Diedrich, the foremost African Americanist in Europe. Each encouraged my work and helped me make key improvements to the manuscript.

I would not have come to many of the understandings that appear in these pages were it not for three institutions where I have done time. The people at Garfield High School in Seattle and the Central District around it nurtured me as a youth and taught me more about the way race works in America than any other single source. The people of Brigham Young UniversityHawaii and the towns of Laie, Kahuku, and Kaneohe helped me understand that identities are not only constructed, but complex and variable. The University of California, Santa Barbara, gave me a place to work, space to pursue my ideas, and colleagues to encourage me. I am especially grateful to librarians at these institutions, among them Riley Moffett, Barbara Lansdon, Sherri Barnes, and Gary Colmenar.

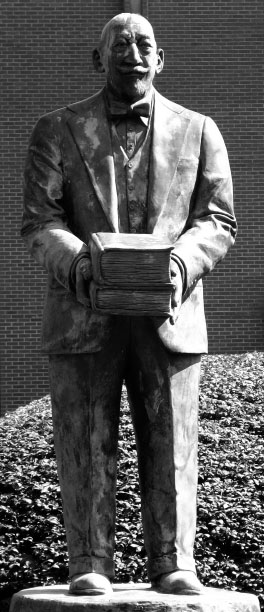

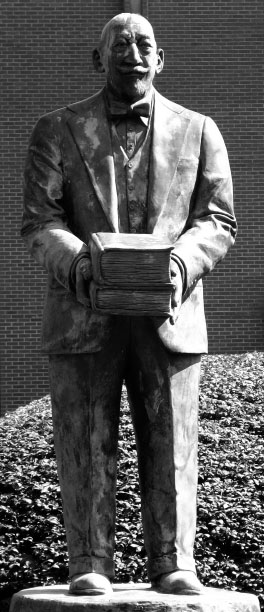

DeAundra Jenkins-Holder of Fisk University went far out of her way to take a photo of the statue of W. E. B. Du Bois that stands on her campus. Special thanks are due to Francisco Beltran and Laura Hooton, whose generous, skillful, and persistent research on another project freed me to complete this one.

For the past couple of decades I have enjoyed the company of the Huian endless stream of brilliant students who have taught me much and who never failed to provide entertainment as they went about their own projects. My wife, Anna Lucky Louise Spickard, has been a constant solace and source of intellectual engagement. My other debts are marked in the notes. By the time you reach the end of the book, you will likely understand why it is dedicated to Winthrop Jordan.

In 1903, W. E. B. Du Bois famously foretold that the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line,the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.1 Surely he was correct. No problem more deeply troubled the American people,2 throughout the century that he was then entering and we have just left, than race, for which Du Bois chose the metaphor, the color-line. Never just a matter of Black and White, race in all its pain and complexity was a problem for America throughout the twentieth centuryfrom Jim Crow segregation to the orgy of lynching that spasmed across the decades; from attempts to wipe out Native peoples by dismantling Indian reservations in the 1920s to the racialized immigration laws of that same decade; from World War II race riots to the incarceration of the entire Japanese American people; from the midcentury fight for civil rights for African Americans to similar movements for the rights of Latinos, Native Americans, and others; from racial divides in opportunity and access to lifes good things (even physical safety) that persisted into the twenty-first century to the racialized anti-immigrant, anti-Mexican, and anti-Muslim movements of our own generation.3

Du Bois lived ninety-five years. He published dozens of books, scores of pamphlets, and hundreds of articles. He wrote on many topics, but race was always at the core of his concern. I want to focus in this prefatory essay on three themes that seem to me to have been especially central to Du Boiss theoretical thinking about race.4

Fig. I.1.

Statue of W. E. B. Du Bois on the campus of Fisk University. Photo by DeAundra Jenkins-Holder. Courtesy of Fisk University.

The first was a tension between seeing race as a biological essence and understanding it as a set of relationships that are constructed in the social negotiations that occur between people. When Du Bois wrote his famous words, race was widely assumed, by him and by others, to be a biological thing. In one of his first published writings, The Conservation of Races, he stated as a certainty:

We find upon the worlds stage eight distinctly differentiated races. They are, the Slavs of eastern Europe, the Teutons of middle Europe, the English of Great Britain and America, the Romance nations of Southern and Western Europe, the Negroes of Africa and America, the Semitic people of Western Asia and Northern Africa, the Hindoos of Central Asia and the Mongolians of Eastern Asia.5

A sentence like this could have appeared in any turn-of-the-century anthropology textbook.6 Looking back from his later years, he reflected, I was born in the century when the walls of race were clear and straight; when the world consisted of mutually exclusive races; and there was no question of exact definition and understanding of the meaning of the word.7 Du Bois even, on occasion, used the language of eugenics, for it was the way that educated people spoke and wrote in his era.

Although he used the language of biology and treated races as permanent and discrete categories, Du Bois knew race in another way as well. He was always conscious that he was constructing his own race over the course of his life. In The Conservation of Races, he continued:

But while race differences have followed mainly physical race lines, yet no mere physical distinctions would really define or explain the deeper differencesthe cohesiveness and continuity of these groups. The deeper differences are spiritual, psychical, differencesundoubtedly based on the physical, but infinitely transcending them. The forces that bind together the Teuton nations are, then, first, their race identity and common blood; secondly, and more important, a common history, common laws and religion, similar habits of thought and a conscious striving together for certain ideals of life.8

Next page