ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

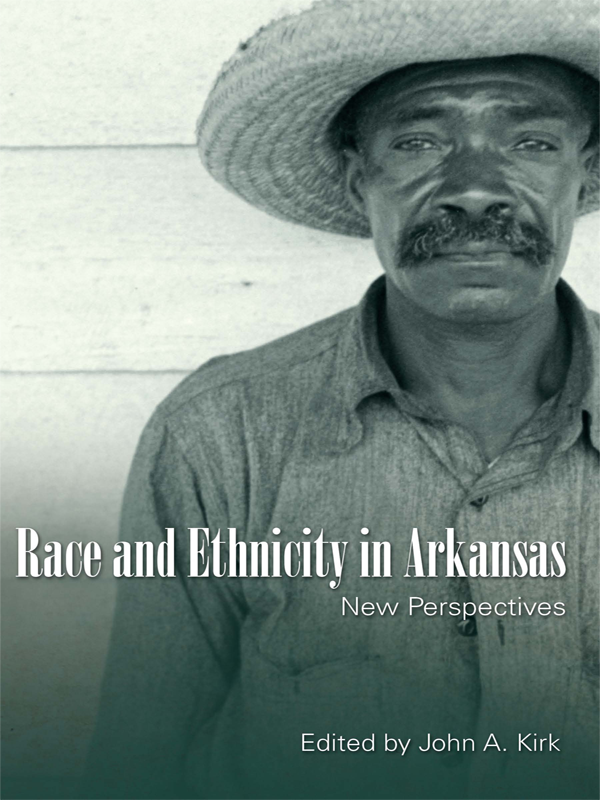

The twelve essays in this collection grew out of the conference Race and Ethnicity: New Perspectives on the African American and Latina/o Experience in Arkansas, sponsored by the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) History Department, the UALR Center for Arkansas History and Culture (CAHC), the Central Arkansas Library System (CALS), and the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies.

The conference was part of a Rockefeller Centennial Celebration to mark the one-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Gov. Winthrop Rockefeller, Arkansass first Republican governor since Reconstruction, who served two terms in office from 1967 to 1971. Rockefeller arrived in Arkansas in 1953 with an already established interest in race and ethnicity. The grandson of Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, Winthrop spent early boyhood holidays at the African American Hampton Institute in Virginia and played an active role on the executive board of the National Urban League while living in New York. In Arkansas, he established a cattle-farming ranch atop Petit Jean Mountain just outside of Morrilton (about sixty miles northwest of the state capital of Little Rock) and put his old friend from New York, African American Jimmy Hudson, in charge as manager. As governor, Rockefeller played an important role in shaping better race relations within Arkansas and promoted a number of African Americans into state offices, including William Sonny Walker, the first state director of the Office of Economic Opportunity in the South. In the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.s assassination in 1968, Rockefeller was the only southern governor to hold a memorial service on the steps of the state capitol in tribute to the slain civil rights leader.

I am grateful to Deborah Baldwin, dean of the UALR College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences and associate provost of CAHC, and to Winthrop Rockefeller Institutes Christy Carpenter, co-chair of the Winthrop Rockefeller Centennial Coalition Executive Committee, for conference funding. I also thank Bobby Roberts, head of CALS, and David Stricklin, head of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, fortheir support. CALS sponsored a conference plenary talk by Douglas Blackmon, author of Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, through its J. N. Heiskell Distinguished Lecturer series. Blackmon, an Arkansas native, provided the perfect launch for the conference, and I am delighted to acknowledge his contribution to proceedings. Two trusty assistants provided valuable help in coordinating conference logistics: Rebecca (Rivka) Kuperman, from the deans office, and Andrea Ringer, then a student in UALRs masters program in public history and now a successful graduate.

Four moderators chaired the four conference panels and kept people on time and in order. My thanks for their willingness to participate go to Adjoa Aiyetoro, inaugural director of the UALR Institute on Race and Ethnicity and associate professor of law at the UALR William H. Bowen School of Law; Ranko Shiraki Oliver, associate professor of law at the UALR William H. Bowen School of Law; David Stricklin, head of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies; and Sherece West-Scantlebury, president and CEO of the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. Jay Barth, M. E. and Ima Graves Peace Distinguished Professor of Politics at Hendrix College, provided the conferences closing remarks. I am also thankful to the authors of the essays in this volume for giving up their time to attend the conference, lending their expertise, providing stimulating and convivial company throughout one long day and two evenings of conference activities, and having the staying power to make it through countless emails, suggestions, and queries from the editor as the conference collection came together.

Finally, the UALR Chancellors Committee on Race and Ethnicity warrants a mention. Since 2006 UALR chancellor Joel Anderson has led weekly Monday afternoon discussions during semesters about issues related to race and ethnicity in Arkansas, the South, and the nation. The voluntarily attended group is made up of faculty, staff, and students and represents an open forum for anyone in the university who wishes to attend. I became part of the committee when I arrived at UALR in 2010, and I have found it a useful and supportive sounding board for my own ideas and a valuable peer group to learn from. In 2011, UALRs Institute on Race and Ethnicity grew out of the committee to provide a more formal structure to, as its mission statement says, remember and understand the past, inform and engage the present, and shape and define the future on issues of racial and ethnic justice. Among its projects, theinstitute has established the Arkansas Civil Rights Heritage Trail in downtown Little Rock to publicly commemorate the many unsung civil rights heroes in the state. All of this is befitting of UALR, whose stated goal is to be keeper of the flame on race in the city, whose African American student population is the largest of any higher-education institution in the state, and which is located in a majority nonwhite state capital.

INTRODUCTION

The Little Rock school crisis attracted international headlines in September 1957 and made Arkansass capital city synonymous with images of racial hatred around the world. Gov. Orval Faubuss use of the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the court-ordered integration of nine black students, who collectively became known as the Little Rock Nine, with two thousand white students at Central High School eventually forced President Dwight D. Eisenhower to act by federalizing state troops and sending in federal soldiers to protect the black students. Quite rightly, the school crisis has attracted a good deal of scholarly and popular attention, but it has also had the unfortunate effect of eclipsing the full richness and diversity of Arkansass experiences with race and ethnicity. Not until relatively recently have studies begun to emerge that move beyond the school crisis to examine the many other episodes that have shaped the states racial and ethnic history. Many of those studies have been or are being written by the contributors to this collection. This volume spotlights their research, which is an essential part of the process of uncovering and rethinking racial and ethnic relations in the state and how they continue to shape it today.

The essays in such as running away to freedom across large distances or, more directly, killing their masters. Of course, not all slaves were able to use the frontier experience or to exercise agency to their advantage in all places and at all times. But the possibility of leveraging their circumstances to exercise some control in the overwhelmingly exploitative situations they faced did exist.

Carl H. Moneyhons essay shows that emancipation posed new issues for freedmen and their former masters. For freedmen, the question was no longer how to resist slavery but how to lay claim to a freedom that they had previously never been permitted to experience. For former masters, the question was how to reconcile the new African American freedom with the same needs that their enforced labor had previously met. Seeking to shape their own destiny, a number of African Americans moved from rural to urban areas in search of new opportunities and safety in numbers. They actively pursued education in an effort to prevent themselves and their children from being swindled out of their newly gained liberty. For those who stayed in the countryside, land ownership as a route to economic independence became a central goal. Meanwhile, whites debated the potential capacities of freedmen. Were former slaves incapable of operating in white society because of their supposed inherent racial inferiority, or was the debilitating historical experience of slavery a shackle that could be undone? Moneyhon determines that the former view triumphed over the latter because of economic and political developments that made continued racism the more expedient choice.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.