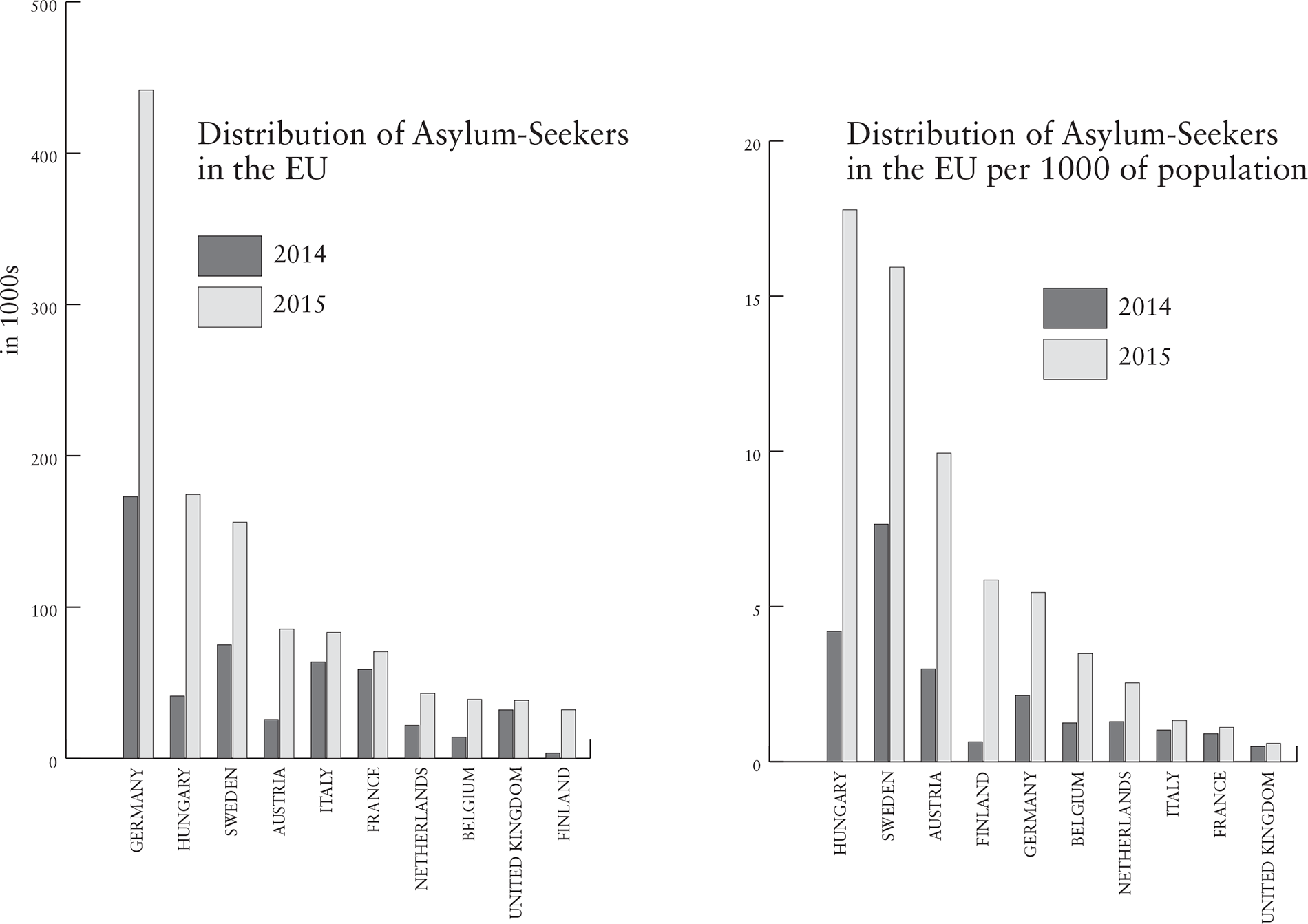

Source: Eurostat

Alexander Betts and

Paul Collier

REFUGE

Transforming a Broken Refugee System

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2017

Copyright Alexander Betts and Paul Collier, 2017

The moral right of the authors has been asserted

Cover illustration David Foldveri

Photograph of Alex Betts Tony Kerr

Photograph of Paul Collier John Cairns

ISBN: 978-0-241-28924-2

List of Illustrations

Illustrations

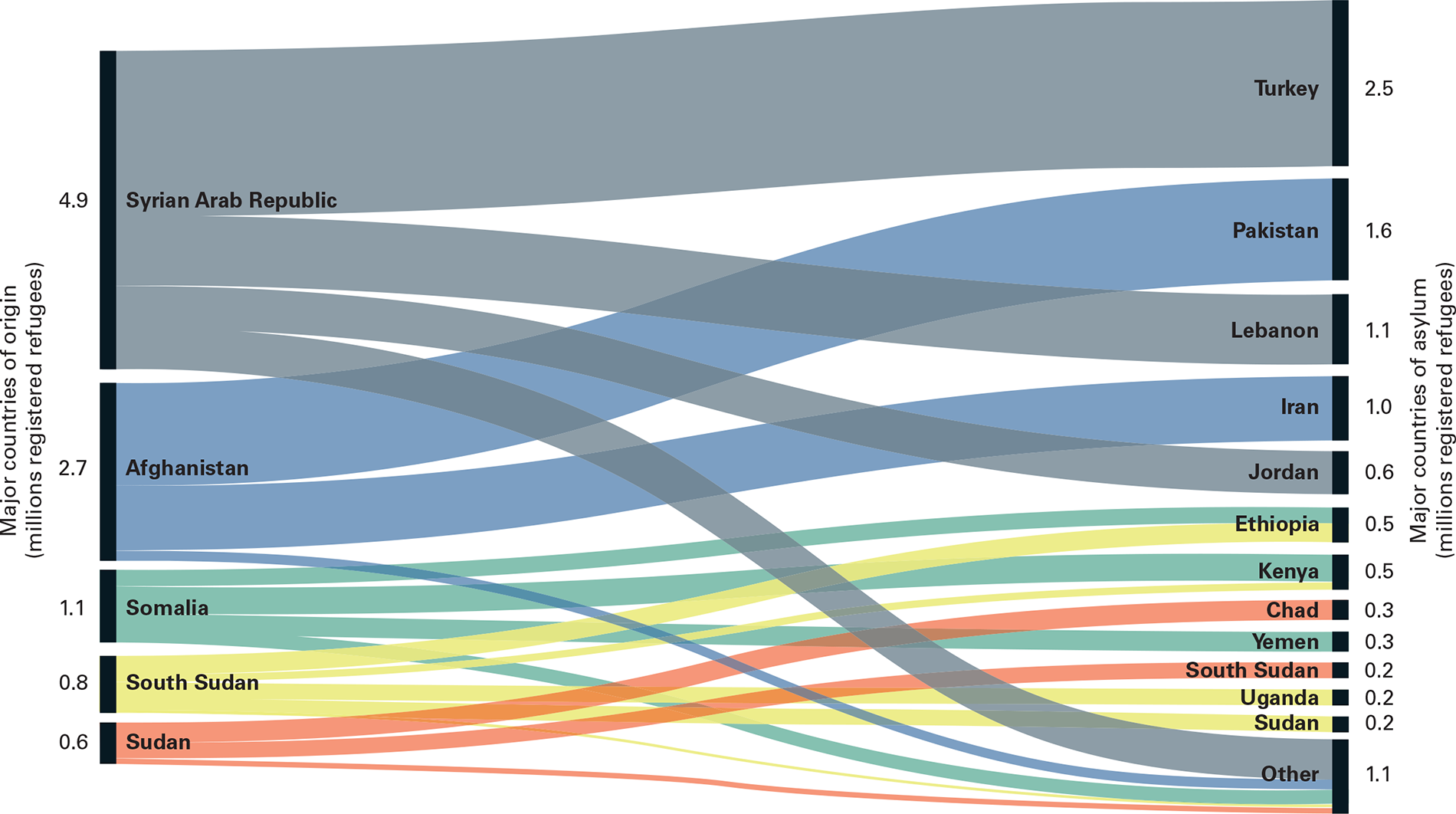

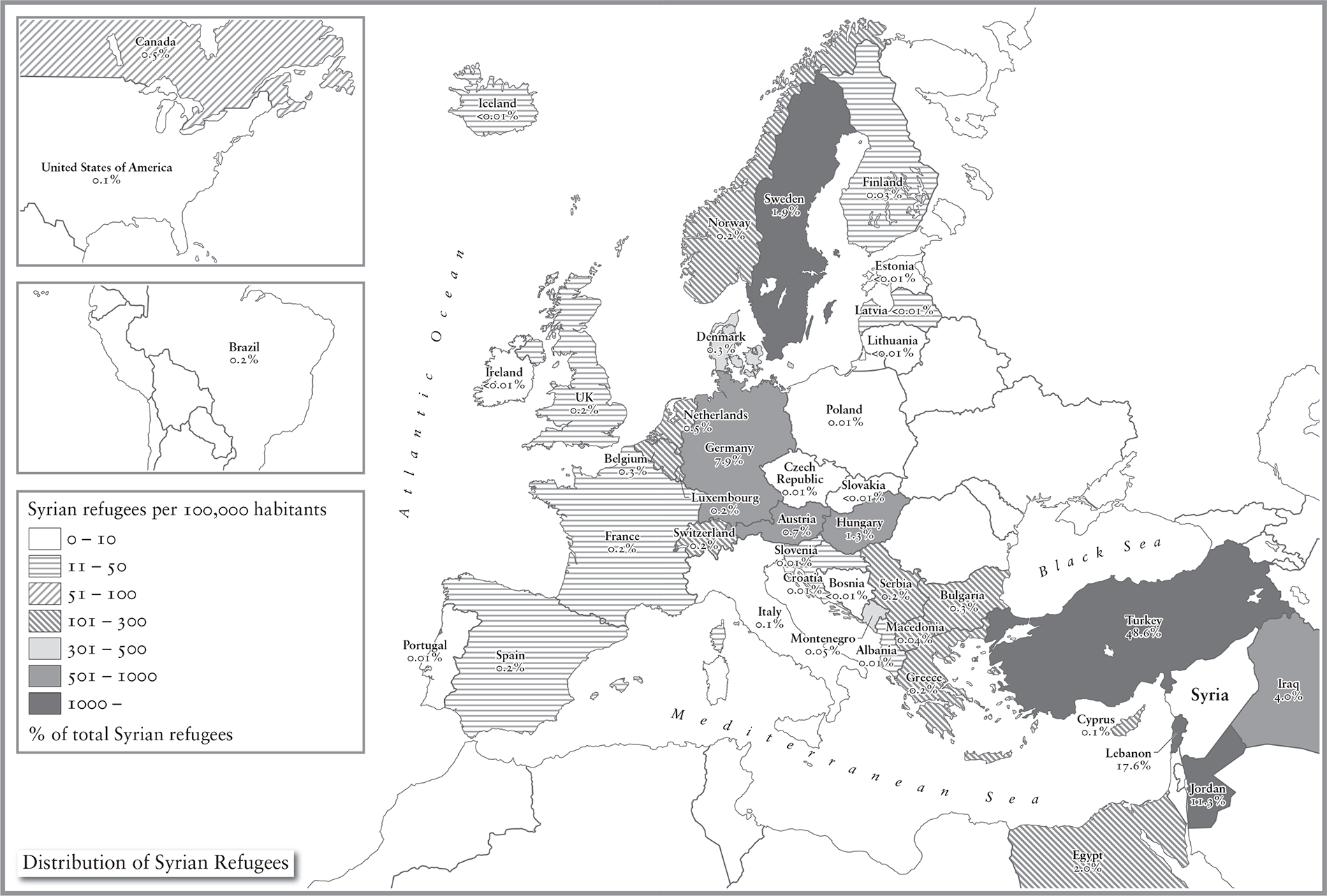

Where refugees from top 5 countries of origin found asylum | end-2015

Source: UNHCR

Women walk between destroyed buildings in the government-held Jouret al-Shiah neighbourhood of the central Syrian city of Homs.

Syrian children at the recently designed Azraq refugee camp in northern Jordan.

A Syrian family living in urban destitution in an apartment block in Beirut, Lebanon.

Satellite imagery of the Dadaab refugee camps in Kenya, which host nearly 350,000 Somali refugees.

Congolese women selling dried fish and vegetables in the Nyarugusu refugee camp in Tanzania, where refugees have no legal right to work.

The bustling Juru market in Nakivale settlement in Uganda, created in 1958 and home to refugees from Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda.

The Shams-lyses market street in Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan. Its name is a play on words that combines the old name for Syria with the famous Parisian avenue.

A makeshift bird shop in the home of a Syrian family in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan. The camp was created in response to the Syrian civil war and hosts around 83,000 people.

Demou-Kay, a Congolese refugee, running his community radio station in Nakivale settlement in Uganda.

Refugees making biodegradable sanitary pads at a social enterprise in Kyaka II settlement in Uganda.

Refugee and local tailors working alongside one another in Kampala. Uganda is one of the few developing countries that gives refugees the right to work.

A factory in the King Hussein bin Talal Development Area (KHBTDA) in Jordan, one of the economic zones where Syrians are gradually being allowed to work.

Syrian men embark on the perilous journey across the Aegean Sea. Around 8,500 people drowned crossing the Mediterranean in 2015 and 2016.

A woman and child refugee from Syria wait at the border to Austria in Sentilj, Slovenia.

Source: UNHCR

How We Came to Write This Book

The collaboration behind this book dates back to an invitation. By early 2015 Jordan was confronting the day-to-day reality of a broken global refugee system. Familiar with our work, a Jordanian think tank, WANA, asked us to come and brainstorm with the government. Neither of us was a Middle East expert: our main geographical interest is in Africa. We were also both outsiders to the narrow range of academic disciplines that have dominated the study of refugees: we are neither lawyers nor anthropologists. Paul is an economist and Alex is a political scientist, though we have each regularly trespassed across the boundary between the two fields. Although Paul had long worked on development and conflict, he had not applied it to the context of refugees. Conscious of do no harm, he routinely turned down requests to stray into unfamiliar territory and would have done so with this one. But to Alex the subject of refugees was not unfamiliar territory: it was his lifes work. By 2015 he was directing the worlds largest centre for refugee studies, at Oxford University. We became a team.

Arriving in Jordan that April, we found that with WANA we had landed on our feet. Its Director, Erica Harper, had all the knowledge of context that we lacked: and more, for her husband was the Director of UNHCR in Jordan. Andrews impressive combination of vigour and intelligence was required: facing mounting needs and diminishing resources, his job was becoming impossible. Through Erica and Andrew we had ready access to the knowledge and networks we needed to remedy our own areas of ignorance.