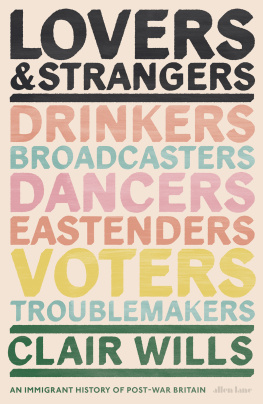

Clair Wills

LOVERS AND STRANGERS

An Immigrant History of Post-War Britain

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2017

Copyright Clair Wills, 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design: Tom Etherington

The author and publisher are grateful to the following for permission to reproduce material:

The Enigma of Arrival, copyright V. S. Naipaul, 1987, and Half a Life, copyright V. S. Naipaul, 2001, used by permission of The Wylie Agency (UK) Limited; The Girls of Slender Means, Muriel Spark, reproduced by kind permission of David Higham; Journey to an Expectation, The Emigrants and The Pleasure of Exile, George Lamming, reproduced by kind permission of George Lamming; The Seventh Man, John Berger, reproduced by kind permission of Agencia Literaria Carmen Balcells; An Irish Navvy: The Diary of an Exile, Dnall Mac Amhlaigh, reproduced by kind permission of The Collins Press; Free Association, Steven Berkoff, copyight Faber and Faber Ltd; Escape to an Autumn Pavement, Andrew Salkey, Peepal Tree Press, reproduced by kind permission of the estate of Andrew Salkey and Peepal Tree Press; In the Ditch, Buchi Emecheta, Heinemann, reproduced by kind permission of the estate of Buchi Emecheta; Dead as Doornails and The Life of Riley, Anthony Cronin, reproduced by kind permission of Anne Haverty; Nirmohi Vilayat, Ranjit Dheer, reproduced by kind permission of Ranjit Dheer; Dukh Pardesan de, Pritam Sidhu, reproduced by kind permission of Surjit Sidhu; Black People, White Blood, Sathi Ludhianvi, reproduced by kind permission of Sathi Ludhianvi.

ISBN: 978-0-141-97496-5

In memory of Beryl Suitters Dhanjal, 19392016

Introduction

About fifty years from now, future historians in Asia, in Africa and perhaps in England writing about Europe in the nineteen fifties and sixties will presumably devote a chapter to the coloured minority group in this country. They will say that although this group was small, it was an important, indeed an essential one. For its arrival and growth gave British society an opportunity of recognising its own blind spots, and also of looking beyond its own nose to a widening horizon of human integrity. They will point out that the relations between white and coloured people in this country were a test of Britains ability to fulfil the demands for progressive rationality in social organisation, so urgently imposed in the latter half of the twentieth century. And the future historians will add that Britain had every chance of passing this test, because at that period her domestic problems were rather slight by comparison with those of many other areas of the world.

Ruth Glass, Newcomers, 1960

The historian seeks to abstract principles from human events. My approach was the other; for the two years that I lived among the documents I sought to reconstruct the human story as best I could.

V. S. Naipaul, The Enigma of Arrival, 1987

Long ago in 1945 all the nice people in England were poor, allowing for exceptions. The streets of the cities were lined with buildings in bad repair or in no repair at all, bomb-sites piled with stony rubble, houses like giant teeth in which decay had been drilled out, leaving only the cavity. Some bomb-ripped buildings looked like the ruins of ancient castles until, at a closer view, the wallpapers of various quite normal rooms would be visible, room above room, exposed, as on a stage, with one wall missing; sometimes a lavatory chain would dangle over nothing from a fourth- or fifth-floor ceiling; most of all the staircases survived, like a new art-form, leading up and up to an unspecified destination that made unusual demands on the minds eye. All the nice people were poor; at least, that was a general axiom, the best of the rich being poor in spirit.

Muriel Spark, The Girls of Slender Means, 1963

You jacked in your part-time job digging ditches for the County Council in Mayo, or helping out on your uncles small farm in Galway, and bought your ticket for Holyhead. You queued and queued in the refugee camp in Germanys British Occupation Zone, for a place on one of the labour schemes which would bring you to a job in a mill in Bradford, or a mine in Wales. You applied by post to a hospital in Lincolnshire from Kingston, Jamaica, and when the letter of acceptance came you borrowed the fare. You sold your plot of land in Jalandhar in the Indian Punjab and paid the money over to an agent who arranged the ticket and passport which would land you at Heathrow. Unless you were a refugee trying to find a way out of the post-war German camps, and had no home in Poland or Latvia or the Ukraine to go back to, you did not imagine spending more than two, or at the most five, years in Britain. You thought of yourself as a migrant rather than an immigrant. You were prepared to give up day-to-day life at home in order to get the training or earn enough money in England to make home viable again. But you did not return. You became a long-term immigrant, a practised reader of the British psyche, adept at living between two cultures, and an expert in geographical gains and losses.

The refugees and migrants who arrived in Britain in the immediate post-war years had to develop new ways of making sense of their lives. They gave up their everyday immersion in the ordinary world of family, village and small-town life for the sake of a future which they could only dimly imagine. They left familiar environments and, as they disembarked at Tilbury, Southampton, Liverpool or London Airport, instantly became strangers. They were marked as outsiders by their language, accents, clothes, customs and, sometimes, their skin colour. Even fifty and sixty years after their arrival in a still largely mono-cultural Britain it is rare to meet post-war immigrants who feel a straightforward sense of belonging, however happy and successful their lives have been. They will always be from elsewhere.

An immigrant history of post-war Britain is in part a history of foreigners, but of foreigners who have given up their place in their own national history in order to play a role in the history of Britain. When I began this book I intended to write an account of Britain in the 1950s and 1960s from the perspective of the many thousands who moved from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Caribbean to power the countrys post-war recovery. I wanted to put the migrants back at the heart of post-war British reconstruction, where they belonged. But I quickly realized that to try to map the stories of immigrants against the established background of British politics and society was to miss something fundamental about migrant experience. Immigrants from Europe and the Commonwealth differed in all sorts of ways but what they shared was the experience of belonging securely neither to the places they had left nor to the place they had chosen to make their home. It was not simply that they lived between two cultures but that they lived in a third space the limbo of migrant culture. This was a world which grew at the meeting point between the hopes, desires and strategies for survival of the immigrants themselves, and the opportunities made available to them. First-generation immigrants lives were circumscribed in all sorts of ways which set them apart from mainstream British culture, and to simply add them in to the story of Britains recovery from the war and the boom years of the 1950s would be to miss both what was unique about their experience, and the ways in which they transformed the mainstream.