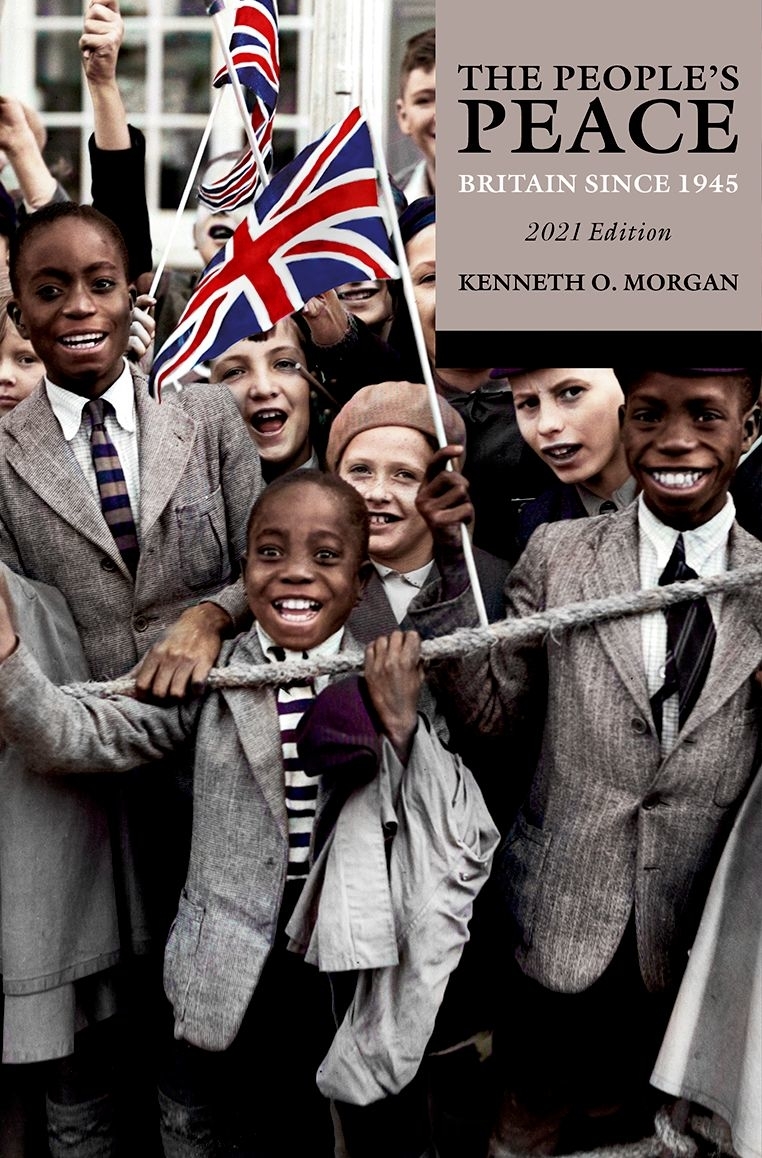

The Peoples Peace

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Kenneth O. Morgan 1990, 1999, 2001, 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First published as The Peoples Peace 1990

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback (with corrections and additions) 1992

Second edition 1999

Third edition published as Britain Since 1945 2001

Fourth and revised edition 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950280

ISBN 9780198841074

ebook ISBN 9780192577825

Printed and bound by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, cr0 4yy

Contents

This new edition essentially follows the text of the original version published in 1990. However, it takes the story on from the fall of Mrs Thatcher to the end of the first year of the Blair administration in May 1998. I have also taken the opportunity to make some small emendations and corrections, and to update the Bibliography.

K.O.M.

Long Hanborough

September 1998

Preface to The Third Edition

This new edition takes the story on from the end of the first year of the Blair government in May 1998 to the general election of June 2001. I have made some small changes elesewhere, and also revised and updated both the Conclusion and the Bibliography.

K.O.M.

Long Hanborough

June 2001

Preface to The Fourth Edition

In this updated edition, the story of modern Britain is continued from 2008 to the Brexit settlement in March 2019. I am particularly grateful for the advice of my daughter, Katherine.

K.O.M.

Long Hanborough

June 2021

The Era of Advance

19451961

National unity, declared Sir William Beveridge in 1943, was the great moral achievement of the Second World War. It rested not on party bargains or formal coalitions but on something far more deeply rootedthe mutual understanding between Government and people. It stemmed from the determination of the British democracy to look beyond victory to the uses of victory, to follow a peoples war with a peoples peace. This time, though, it would be utterly different. The past would be exorcized and the future transformed.

Since that time, almost all subsequent interpretations of the history of Britain after 1945 have viewed it as a time of decline or eclipse, both external and internal. Yet the heady impact of the Second World War long exercised its magnetism on a variety of commentators. Across the political spectrum, they saw the experience of Britain between 1939 and 1945 as offering a last, fleeting vision of national greatness. Mrs Thatcher, Prime Minister throughout the 1980s, made frequent attempts to evoke the spirit of Winston Churchill, a symbol of great-power status and indomitable resolve. The fact that the real Churchill was a paternalistic one-nation Whig of romantic disposition, concerned after 1951 to recapture aspects of the social reformism of his younger days, was set aside. For the right, the war embodied constructive patriotism and the will to victory. For the centre-left progressive, it rather implied social cohesion, Keynes-style budgetary management, economic planning, the human version of social citizenship embodied in the Beveridge Report in 1942. It offered the intellectual and historical underpinnings of the post-war consensus. Further to the left, politicians like Michael Foot or even (at times) Tony Benn would look back to the war as a crucible of social revolution, as George Orwell had done in The Lion and the Unicorn, achieved in the classless sacrifice of the Blitz and military service, and taken much further by the Labour government of Attlee after 1945. Michael Foot, then Labours leader, spoke in these terms during the general election campaign of 1983.

In a variety of ways, often instinctively felt, the Second World War supplied images that were satisfying and self-confirming. It was crucial to Britains usable past, as Americans and others interpreted it. By the 1980s, the late war was almost as much a part of a thriving heritage industry as were Tudor manor houses or medieval cathedrals. Tourists queued up to view the War Cabinets subterranean quarters in central London. The successive volumes of Martin Gilberts biography of Sir Winston Churchill attracted massive publicity, while the fiftieth anniversary of the outbreak of war in 1989 launched a huge flood of literature of all kinds. Wartime films such as Brief Encounter or In Which We Serve retained their popularity. The monarchy, following the crisis of Edward VIIIs pre-war abdication, gained new strength through memories of George VIs wartime tours of bomb-ravaged cities, while the Queen Mother lived on as a surviving, ever-popular heroine of the Blitz. Enthusiasts for the arts looked back to the origins of wartime state patronage through the work of the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA) and the image of cultural solidarity conveyed by Myra Hesss piano recitals in the National Gallery. On a popular level, Vera Lynns ballads about the White Cliffs of Dover and Meeting Again made her the forces sweetheart for ever. Conversely, young hooligans, travelling to support the England football team overseas, expressed themselves through anti-German chants dating from the propaganda operations of Hugh Dalton at the Ministry of Economic Warfare during the wareven if, oddly enough, they were combined with Nazi-type salutes and raucous racist sympathy for the National Front. It was not unknown in Britain in the late 1980s for social workers to discover German schoolchildren beaten up in British schools they attended, even if the causes or course of Anglo-German hostilities were quite unknown to either assailant or victim. Both were stereotypes of an ideal of national greatness on which the post-imperial sun refused to set. As late as July 1990, a Cabinet minister, Nicholas Ridley, gave vent to fierce anti-German sentiments and evoked comparisons with Hitler in discussing present-day German attitudes towards the European Community. On this occasion, however, Mrs Thatcher, who was thought to share many of these sentiments herself, was compelled to ask him to resign.