Minnie Lansbury: Suffragette, Socialist, Rebel Councillor

by Janine Booth

Published in 2018 by Five Leaves Publications

14a Long Row, Nottingham NG1 2DH

www.fiveleaves.co.uk

www.fiveleavesbookshop. co.uk

ISBN: 978-1-910170-58-8

Copyright Janine Booth, 2018

Foreword

The story of Minnie Lansbury may be a century old, but it is the story of modern, British political struggle. Like many of those on the frontline of todays fight for fair pay, terms and treatment at work, Minnie was from a migrant background. Her Jewish family had not long before fled from Poland to the melting pot of Londons East End. Then, like now, foreign workers were being identified by both elements of the popular press and mainstream political discourse as outsiders who not only take jobs but undercut wages and conditions. Of course there are subtle nuances with this analysis. Many on the left today are quick to explain that although this is true, it is employers themselves, emboldened by decades of anti-trade union legislation, who use migrant workers to undercut British workers.

But inherent in this analysis is the underlying notion of them and us as if the struggles of British workers and migrant workers were somehow separate, somehow different. Although considered as champions of equality, the historical relationship between trades unions and migrant workers has varied, from the solidarity shown to the strikers in saris at Grunswick to darker chapters where the forerunner of Unite, the TGWU colluded with employers to bar West Indian bus drivers.

The reality is, as Labour history has shown, foreign workers are the working class. Their struggles are our struggles. Their treatment today is what is planned for us all tomorrow.

And therein lies the beauty of this work on Minnie Lansbury. It is a history that focuses on a woman whose struggle so often encapsulated the multi-dimensional reality of intersectional class struggle one that is more relevant today than ever. Working class and Jewish; against war but supported its victims; socialist and feminist; Labour Party member and Communist; a unifier and a rebel; a suffragette who didnt stop when some women got the vote.

The struggle against oppression in all its forms has a long and rich history in our movement. But it is not a foregone conclusion this will always be so. Division and sectarianism on the left is never far away. This wonderful history of Minnie Lansbury reminds us what can be achieved when it is rejected and solidarity with all who struggle, embraced.

Clive Lewis MP

Labour, Norwich South

The Search for Minnie Lansbury: introductionand acknowledgements

I first met Minnie Lansbury when reading about the Poplar Council rates rebellion which shook London in the aftermath of the First World War. Of the thirty councillors who went to prison to win a significant redistribution of the capitals local government funding, she was the youngest and the first to die. A memorial clock on Bow Road bore her name, but few people seemed to be aware of who she was and what she did. I thought that East Enders, historians and left-wing activists could benefit from knowing more about her, and that recording the contribution of a woman, a second-generation immigrant and a Jew would help a labour movement which still struggles to involve and fight effectively for these groups.

The more I learned about Minnie, the more I uncovered the fascinating backstory of this daughter of impoverished Polish Jews who grew up among rebels and became part of the radical East End labour movement. She worked behind the scenes but still found herself thrust into the limelight, most notoriously in the manufactured scandal with which this book opens. This was one alongside many other tensions in Minnies life: between tradition and modernity; religion and secularism; being married and remaining independent; her immigrant community and her host country; her quiet personality and her need to speak out.

Tensions presented choices, and Minnie shaped her life by the choices she made. She chose to campaign for votes for all not just for ladies, to leave her teaching job and work full-time for the East London suffragettes, and to break the law and not back down when faced with prison. On other issues, she rejected the apparent dichotomy and refused to choose one option over another: she opposed war but still supported its victims; joined both the Labour and the Communist Parties; and was both a socialist and a feminist.

Some biographers face the onerous task of sifting through a large quantity of material about their subject and selecting the most interesting and relevant. Writing the life of Minnie Lansbury, however, presented the opposite challenge. Minnie left little record of her life. She was not a writer or a public speaker, and only in the last two years of her life held public office for which records survive. Moreover, the recorded history of the labour movement tends to focus on male leaders, and that of the suffragette movement on well-heeled women. Minnie was neither.

Uncovering her story therefore involved seeking out every snippet available from every possible source. I owe great appreciation in this to the various archives listed in the bibliography and their always-helpful staff. I offer a special mention to Malcolm Barr-Hamilton, recently retired from Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archive, who has supported my research into Minnies life for several years.

Collecting every snippet still left gaps in her record. Filling these required a little informed speculation. For example, the page of Chicksand Street Schools Admission and Discharge Register for the year that Minnie started school is missing, but those for all six of Minnies surviving siblings are preserved, so although there is no record for Minnie herself, we can confidently conclude that she took the same short walk to the same school as her sisters and brothers. Other speculation is based on records of similar lives and knowledge of the places and cultures in which she lived and worked, but I have tried to avoid wild guessing!

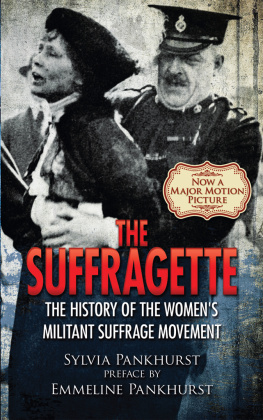

Most of the written personal descriptions we have of Minnie are written by Sylvia Pankhurst, who penned vivid descriptions of her black, sparkling eyes and gay demeanour. This was very much Sylvias writing style, and Minnie featured strongly in her life for several years. The other indispensable source of more personal information about Minnies life came from her great-niece Dr Selina Gellert, who has become a good friend as well as a great help. Thanks are also due to other relatives of Minnies fellow Poplar Councillors, specifically Nigel Whiskin, Terry Lansbury, Steven Warren and Chris Sumner.

Telling Minnie Lansburys story has become something of a mission for me. I have been sustained in this by the various people and organisations who have provided a platform for me to talk and write about her, including the Jewish Socialists Group, Workers Liberty, Islington Libraries, Central Foundation Girls School, Tower Hamlets Ideas Stores, the East London History Society, the East London Womens Museum, The Clarion magazine and the Jewish East End Celebration Society.

I could not have pursued this research to its conclusion in this book without the tolerance and support of my partner John, sons Alex, Joe and Harrison, and parents Jean and David. And the book itself would have been of poorer quality without guidance from Dr Catherine Fletcher.

A biography is rarely the story just of the individual, but also tells of the communities, movements and places in which she or he lived. Through telling the story of Minnie Lansbury, we can both memorialise a remarkable woman and learn again the stories and the lessons of the struggles of which she was part, and of the events and times in which she lived, fought and died.

Next page