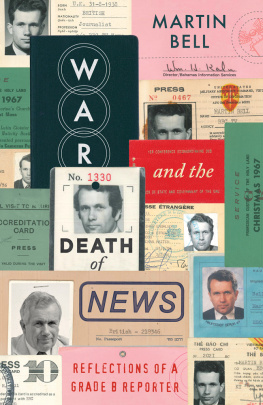

PRAISE FOR MARTIN BELL AND

WAR AND THE DEATH OF NEWS

In prose as crisp and hard-hitting as the bullets hes dodged for decades, Bell sounds the alarm for a TV journalism thats under fire as never before. Its typical Bell unflinching truth-telling, brilliantly argued; a clarion call to everyone who cares about powerful journalism in a world that needs it more than ever.

Bill Neely, chief global correspondent, NBC News

Martin Bell was the finest foreign correspondent of his generation. Night after night on the BBC, we watched him find the front lines and report back to us what he and his camera crews discovered that day. His reporting was honest, courageous, compassionate and clear. The same virtues are evident in this fearless memoir of his work over thirty-five years. With wisdom, candour and integrity, he describes the irony and tragedy of the wars, revolutions and riots he covered in violent places all over the world. He is especially critical of those editors at home who kept the public from seeing the ugly truth of what was going on in places like Bosnia, Iraq and Israel. This is his masterwork.

John Laurence, author of The Cat from Hu:

A Vietnam War Story

He was our rock, steady, trustworthy, a man who would look after not just his own crew, but the whole British press corps, if need be.

John Sweeney, investigative journalist and author

For Merita

Contents

Introduction

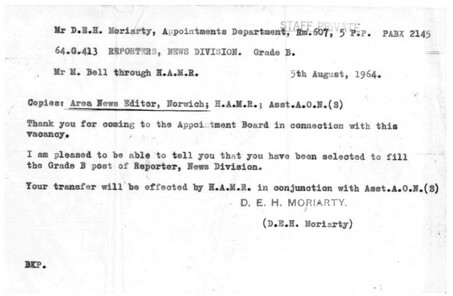

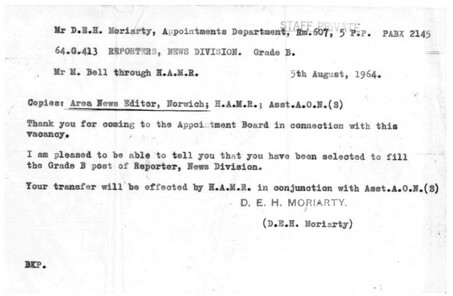

On 5 August 1964 I was sent a memo by Mr D.E.H. Moriarty of the BBCs Appointments Department in London: I am pleased to be able to tell you that you have been selected to fill the Grade B post of Reporter, News Division.

I was working at the time in the newsroom of the BBC in Norwich. We specialised in rural planning disputes, horse shows, farm gate interviews, fatstock prices, flood drainage schemes in the Fens and the fortunes of our football teams. If I was lucky I would travel to Portman Road to interview Alf Ramsey, manager of Ipswich Town and later of England. If I was unlucky I would be sub-editing copy about Peterborough United for the regional radio news. For my metropolitan audition, in the basement of Broadcasting House in London, I reported on the state of the East Anglian bean crop: It has failed because of a disease called halo blight. This starts out as a circular patch on the leaf of the plant hence the name then spreads down to rot the stem. It is bacterial. It is contagious. And it is causing a whole lot of trouble to the frozen foods firms.

Nevertheless, they gave me the job and I moved from Norwich to London a month later. Being an ambitious young man, I wondered who were the Grade A reporters. I soon found out. They were the likes of Peter Woods, formerly of ITN and the original foot-in-the-door man of TV news. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan complained: Whenever I open the door, theres this huge man with a microphone! They covered the big bank robberies in Wood Green and Lambeth. I covered the small bank robberies. They did the big fires. I did the small fires. They asked questions on the Prime Ministers doorstep. I interviewed junior ministers at the Queens Building in Heathrow on their return from insignificant overseas missions. They were inside Parliament. I was outside it. They were covering the lying-in-state of Winston Churchill in the Great Hall of Westminster. I was freezing with the crowds on Lambeth Bridge. They were in the Congo for the civil war and the secession of Katanga. I was at Ascot to report on the fashions of Ladies Day. There was a perennial celebrity there, a Mrs Shilling, who made sure of her press coverage by wearing a hat made entirely of newspaper cuttings. I went on from there in March 1966 to report the theft of the World Cup trophy, which was retrieved by a dog called Pickles. It was because of the trespasses of Peter Woods that Number 10 eventually penned the press behind a barrier on the far side of the street. He was also the father of Justin Webb, a considerable broadcaster himself. I had to replace Justin once in Bosnia, in circumstances more dangerous for me than they were for him. If you have been around long enough, everything connects.

You know where you come from, but have no idea where youre going to until you have got there, by which time it is too late to take the road less travelled. The world changed beyond recognition and TV news changed with it. It became a player, not a peep-show, and a shaper of our impressions of people and politics. Anything could happen and did. I moved on to eighteen wars and more than a hundred countries, and even served for a term in the surrogate war zone of the House of Commons. But it started with the bean harvest, the Ascot hats and the dog called Pickles.

The chapters that follow are based on the news despatches, documents and diaries of the time. They are the memoirs, reflections and conclusions of a Grade B reporter. If only, I sometimes wondered, I could have made it to Grade A.

Once a Soldier

The family was military on my mothers side and literary on my fathers. It included a brigadier, a director of music of the Band of the Life Guards, the news editor of the London Observer and the founder of The Times crossword puzzle.

The two strands connected in the Second World War. My uncle the Brigadier, who was a German-speaker in military intelligence, assured us that the flat lands of Suffolk would be squarely in the path of the German Panzer divisions in the event of an invasion, which he thought likely. We therefore left as evacuees to Grayrigg in Westmorland, remote from the war and beyond the reach of Panzers and Luftwaffe. We sometimes forget what a close run thing that was. My father Adrian Bell, the crossword puzzle king, was also an accomplished author who wrote with a battered old typewriter and an even older quill pen. His first book, Corduroy , was a widely read celebration of farming in Suffolk before its mechanisation, which he lamented. Many soldiers carried the paperback Penguin version to the war in their kitbags as a reminder of the England that they thought they were fighting for, although it was already vanishing when he wrote about it and his book was in a sense its epitaph. Whatever else they left behind they kept Corduroy , even on the march from Dunkirk to a German prison camp. He kept in the drawer of an oak chest an envelope full of postcards and letters marked Kriegsgefangenenpost from British POWs in Germany, and others from Italy and even Singapore. His book about farming in Westmorland, Sunrise to Sunset , was translated into German. After his death in 1980, Harry Hespe, a former POW in Changi Jail, wrote to me that he had learned whole passages of Corduroy by heart. My father lifted his spirits: Nightly his writings transported me in memory from a bug-ridden prison cell to the cool English countryside.

We returned to Suffolk when the threat of invasion receded slightly. My father, who was not a military man (too young for one war, too old for the other), joined a group called the Land Defence Volunteers, a predecessor of Dads Army . He recalled later that they had practised standing beside barricades of farm wagons brandishing pitchforks and shotguns, preparing to delay the Germans long enough for their families to escape. They were also instructed to look out for German paratroopers. To cope with these, wrote a company commander in Lavenham, we defend our villages and have our patrols out just before daylight and after daylight. Defensive lines were established between concrete blockhouses that are still standing but overgrown. The railway line was to be blocked by iron struts provided by the Royal Engineers.

Next page