ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The bibliography lists the major sources I consulted during my research, but I owe special thanks to certain individuals who were of particular assistance. These include my agent, Don Fehr, and his assistant, Brittany Lloyd, at Trident Media, and my editor, Stephen P. Hull at the University Press of New England, all of whom had faith in this project from the very beginning. Rosemary James and Joe DeSalvo at the Faulkner Society in New Orleans were consistent in their support, as were the following: Gail Malmgreen at the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives at New York University; David M. Hardy and Dr. John Fox at the Federal Bureau of Investigation; Mike Ballard, Amanda Carlock, Ryan Semmes, John R. Dickerson, Neil Gilbeau, and Dr. Roy H. Ruby at Mississippi State University; and Erin McAfee at Rice University. Invaluable background information came from American historians Dr. Richard Spence, Edward Jay Epstein, J. Mitchell Johnson, Joseph Albright, Gary Kern, Peter N. Carroll, Eugene Michalenko, Paul E. Richardson, and Christopher Marcisz; and in Britain, Ronald Payne, Nigel West, Vin Arthey, and Dr. Roger H. Platt. Jeff Belmont was also of great help, as were Barbara Belmont, Nancy Ambrosiano, John Raughley, Lisa Roper, Matthew Lutts, Tim Davis, Philip Duerden, and Gay Search. Additional thanks go to the UPNE production and promotion team: Ann Brash, Cannon Labrie, Thomas E. Haushalter, Rick Henning, and Sherri L. Strickland.

AFTERWORD

A summing up of the Cohens espionage career might read this way: They were talented, dedicated, worldly spiesan urbane, jet-set couple loyal to their service, and very good at their work. They were blessed with wit and charm, and loyalty to their friends. Most people they met seemed to think they represented the best of America. The Soviets certainly thought so.

But fighting the good fight against Nazis and Fascists was one thing. Choosing to spy against ones own country in the process was quite another. Morris and Lona could not keep their idealism in perspective. They made the conscious decision to devote their lives to working for a political system that was just as evil as the ones they had sworn to defeat.

When the Cohens controller Willie Fisher went on trial in in 1957 in New York, his lawyer admitted that he was a spy for an enemy power but insisted that he was also a dedicated servant of his country, deserving the same legal compassion as an American agent who might get caught in Russia. And when Konon Molody was tried in London, the court was told that although he was the directing mind in the Portland spy ring, his conduct was not stamped with dishonor. What he did, he did for his country. His arresting officer, Detective Superintendent Smith, admitted that he liked the man.

The Cohens did not receive such an agreeable appraisal. They were branded turncoats by the public, the press, and the governments of Britain, the United States, and Canada. Their treachery had betrayed the entire Western alliance. They were attacked in a torrent of hatred and obloquy. In a word, they were dirty Reds.

But Morris and Lona never saw it that way. They were convinced that during the war, the Soviets hadnt been on the wrong side any more than the British were, or the French. They felt they were just as American as anybody else; that they had not spied to harm their country but to assist a wartime partner in attaining nuclear parity so that a balance of power could be assured and another world war prevented.

This, despite the fact that Morris, as far back as 1954, admitted that Stalin had made certain mistakes. It wasnt much of a criticism but it was an improvement over the days when the Cohens faithfully defended Uncle Joe at every turn. And their suspicions toward the Soviet system grew as they got older.

When it comes to freedom, there were certain shortcomings in the Soviet Union, Morris told a KGB interviewer four years before his death. In the past ten years, life was much more difficult than before. The past ten years revealed a great deal that we did not know about deeply.

They were politically disillusioned, said Svetlana Chervonnaya, a Russian historian who befriended the Cohens after they went into the KGB nursing home. Chervonnaya heard Lona denounce the Soviet system as outright totalitarianism.

Still, the Cohens were proud of their role in stealing the secrets of the atomic bomb. They felt they had done the truly dangerous work of traveling across wartime America to recruit assets and pick up stolen documents at a time when people were being pulled off trains and arrested just because they somehow didnt look right. They worked under a shadow of the gallows while Ethel and Julius Rosenberg stayed in New York and served mostly as a conduit for goods brought in by other agents.

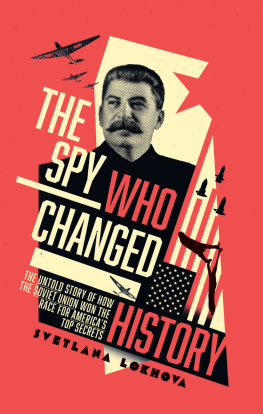

David Greenglass, the Rosenbergs, and Klaus Fuchs all made contributions to stealing Allied nuclear secrets, but the Cohens ran the only Soviet network dedicated to atomic spying, and Lonas famous Kleenex box contained Ted Halls complete diagram of the first A-bomb. Thats what Lona meant when she told Chervonnaya the Rosenbergs got the credit for stealing the atomic bomb, while the Cohens were overlooked.

The Cohens knew they were historical figures who had pulled off what was undoubtedly one of the most damaging espionage coups of all time. But as their lives drew to a close they came to miss America and their families. It tugged at them like the cry of a sick child.

They tried to regain their American souls. They wanted to be Americans again, to die as Americans, to be buried in America. But the time had long since passed when they could have gone home, under any circumstances. A sister came to visit Lona in the Moscow nursing home, but that was the only contact she had had with her family since she and Morris left New York forty-two years before.

Am I a traitor? Lona asked Chervonnaya one day from her hospital bed.

She and Morris both had become obsessed with that word. They spent hours analyzing its nuances. Morris, the dependable intellectual, talked about the relativity of history, how an act denounced as a betrayal might someday be vindicated by history. He wanted someone to write about Lona and himself, or make a film about them, to tell their story once the Cold War was over.

Lona, as always, saw it from the emotional side. On a gray December afternoon as she lay dying of cancer, she again denied she was a traitor. I didnt kill anybody and I didnt destroy any American life, she told Chervonnaya. No American soldier died because of what I have done.

But the word stayed with them to the end.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adjutant General, U.S. Army. Historical Record, 3233d Quartermaster Service Company. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Albright, Joseph, and Marcia Kunstel. Bombshell: The Secret Story of Americas Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy. New York: Times Books, 1997.

Andrew, Christopher. The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5. London: Allen Lane, 2009.

Arthey, Vin. Like Father Like Son: A Dynasty of Spies. London: St. Ermins Press, 2004.

Baruch, Bernard M. Baruch: The Public Years. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1960.

Benson, Robert L., and John R. Schindler, LINK: The Greatest Intelligence Disaster in U.S. History, National Security Agency Cryptologic History Symposium, October 31, 2003.

Bentley, Elizabeth. Out of Bondage: The Story of Elizabeth Bentley. New York: Devin-Adair, 1951.

Blake, George. No Other Choice: An Autobiography. New York: Simon and Shuster, 1990.

Bond, John A. Soviet Espionage and a Polish Girl from Adams,

Next page