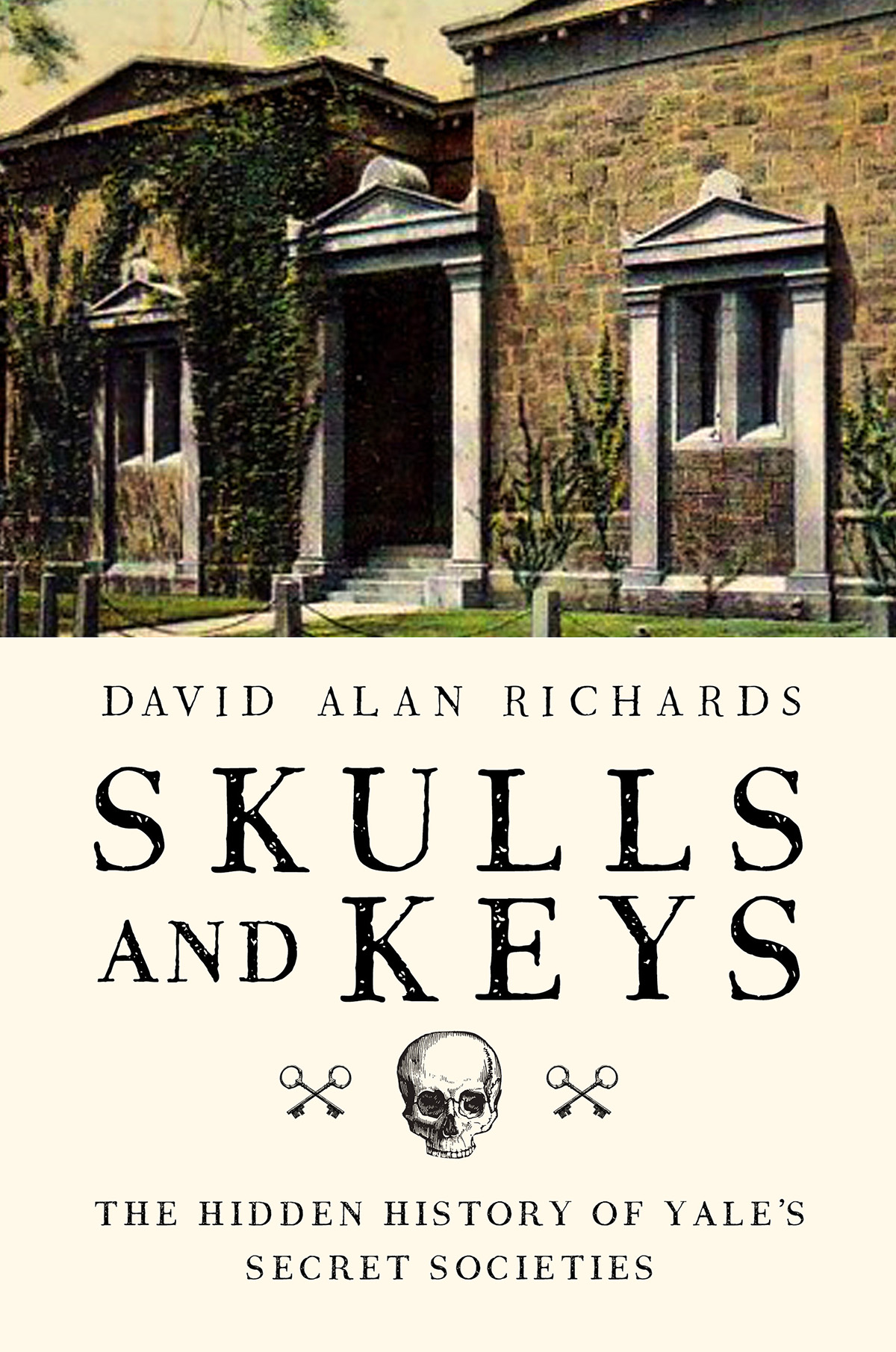

SKULLS

AND KEYS

THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF YALES SECRET SOCIETIES

DAVID ALAN RICHARDS

SKULLS AND KEYS

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2017 David Alan Richards

First Pegasus Books edition September 2017

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-517-3

ISBN: 978-1-68177-581-4 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

Dedicated to

Reuben Andrus Holden

Class of 1940

Skull and Bones

Secretary of Yale University, 1953 to 1971

Fellow of Davenport College

and

Maynard Mack

Class of 1932

Scroll and Key

Sterling Professor of English, 1948 to 1978

Fellow of Davenport College

Off the campus, directly at the end of their path, a shape more like a monstrous shadow than a building rose up, solid, ivy-colored, blind, with great, prison-like doors, heavily padlocked. It is a scary sort of looking old place, said McCarthy. It stands for democracy, Tough. And I guess the mistakes it makes are pretty honest ones.

Owen Johnson, Stover at Yale (1911)

Young men had to find some way to give body to that system of idealism... discovered to exist at New Haven. There was not much in the classroom, on the evidence, to excite the mind, train it, bring it into useful support of healthy principle. With considerable ingenuity, therefore, the undergraduates turned elsewhereto the feelingsto find a possible source of energy. They constructed in the senior societies, with admirable insight, a mechanism to mobilize the emotions of the selected few to their high purposes. Exactly how this was done, how in nine months, in weekly meetings, in secret places, whole lives were changed, is past all discovery. Such special election produces no doubt a sense of large responsibility; the compressions of the secret can generate great energy. At any rate, for most of those engaged, it worked.

Elting E. Morison, Turmoil and Tradition: A Study of the Life and Times of Henry L. Stimson (1960), on Henry Stimson (Yale Class of 1888, Skull and Bones, son of Lewis Atterbury Stimson, Yale Class of 1863, Scroll and Key)

Apropos of Yale and American Colleges generally, could you put me on the track of any book that gives the history of college societies. Its a thing that I am a good deal interested in.

Letter of Rudyard Kipling to John S. Seymour, October 17, 1898

CONTENTS

T his history is about one year in the college curriculum, in one institution, repeated over the course of more than two centuries. The senior year at Yale, this nations third oldest college, has birthed and nurtured student associations called senior societies, more familiarly known now as secret societies. Their fame has gone far beyond that of typical college fraternities. Called by the leading historian of nineteenth-century American college students perhaps the most unique student institutions in the country, they have played a seminal role in the history of both Yale and the nation.

Election to a senior society in New Haven occurs annually in the spring, when groups of fifteen seniors choose their successors in the junior class for clubs where the members names and elections may be public, but their subsequent activity in windowless, fortresslike tombs very private. These groups at YaleSkull and Bones, Scroll and Key, and Berzelius, all founded before the American Civil War, to be followed in succeeding decades by the establishment of Book and Snake, Wolfs Head, Elihu, Manuscript, and numerous underground societies of seniors without their own buildingsare for good reason more popularly known, on campus and off, as secret societies. But so, too, were their forebears, Phi Beta Kappa from 1778 most prominently among them.

Their arcane rituals, particularly the annual day of elections known as Tap Day, have fascinated the public for over 175 years (the New York Times reported the names of those elected beginning in 1886). The first real secret of these organizations is their original purpose: self-education by and through exercises with their fellow students, when their founders believed their college did not or would not provide that education. This remains true to the present, although what is sought now is as much emotional as intellectual stimulus.

Soon, however, election to their small numbers became the summit of a Yale College career. The societies were compelled to defend their exclusivity and the privilege of their privacytheir secrecyby making election choices which were seen on campus to be democratic, rewarding with the prestige of membership in their last year collegians who had excelled in undergraduate endeavors of all kinds. The senior societies became in time more democratic and diverse, incorporating into their numbers over the years talented outsiders (Jews and blacks, other non-Protestant ethnics, scholarship students, and finally women), and easing the passage of previously dismissed castes into the American establishment, decades before their elders and betters followed suit in the higher councils of the university and the nation.

The statistical insignificance of the sample population, and the brevity of the experience, should consign the subject of Yale senior society membership to the dustbin of undergraduate nostalgia. Although a statistical sliver, at 15 percent, of their respective class cohorts, in one college among hundreds in this country, these young men nevertheless went on to become among the most prominent leaders in American politics, diplomacy, law, literature, publishing, journalism, higher education, religion, finance, the ministry, physical and social science, philanthropy, and the counterintelligence services.

To take only the category of national politics, all three of the presidents of the United States who attended Yale College (William Howard Taft and the two Bushes) were members of Skull and Bones, and indeed were the sons of members of that society. More recently on the major parties presidential tickets were senior society members John Kerry and vice presidential nominees Sargent Shriver and Joe Lieberman for the Democrats, with a near-miss presidential nominee two generations before in Robert A. Taft for the Republicans. Moreover, six of Yales sons who became secretaries of state, both of her chief justices of the Supreme Court, and three attorneys general were members. So were three secretaries of the treasury (most recently, President Trumps), two secretaries of war, two secretaries of defense, two directors of the Central Intelligence Agency, one secretary of the army, one of three secretaries of the navy, two treasurers of the United States, and Yales single secretary of commerce and only postmaster general.

Next page