Contents

For Raymond Morell, and in memory of Neil Smith (19542012): proof that James Connolly was not the last Marxist to be born in Edinburgh

2014 Neil Davidson

This paperback edition

published in 2014 by

Haymarket Books

PO Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

info@haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-60846-355-8

Trade distribution:

In the US, Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

In the UK, Turnaround Publisher Services, www.turnaround-uk.com

All other countries, Publishers Group Worldwide, www.pgw.com

Cover design by Eric Kerl. Cover image of New York City long-distance telephone operators voting to strike in 1945, from the Cleveland Press, Special Collections, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University.

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and the Wallace Action Fund.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

Preface

This book, the first of two collections to be published at Haymarket in 201415, consists of essays published between 1999 and 2013, presented in order of appearance.

By chance rather than design I have approached representatives of the classical Marxist tradition discussed here in slightly oblique ways. I trace the development of the concept of progress (and related notions such as advanced and backward) in the thought of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels through the prism of their changing attitude toward the Scottish Highlands. I explore Leon Trotskys life and legacy through an examination of the image of him presented in Deutschers magisterial, but subtly misleading, biography. Antonio Gramscis work has been contested perhaps even more strongly than Trotskys, not least because his prison notebooks have provided such a fruitful basis for multiple conflicting interpretations: here I attempt to show how some notable misrepresentations arose by following the process of their reception in Scotland. Finally, I consider the relationship to classical Marxism of Walter Benjamin, a figure who, while sharing many interests with Gramsci, is, unlike him, generally regarded as belonging to the Western Marxist traditiona categorization that, in part at least, I dispute. The chapters devoted to more recent thinkers are more conventional in form, mainly because the occasions for which they were commissioned or composedbook reviews in all but one caselent themselves more easily to career overviews.

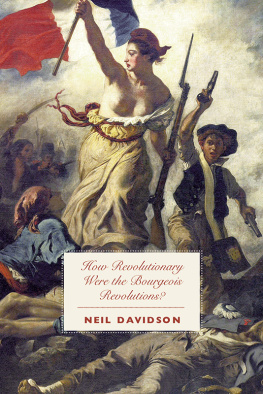

All of these essays were written in or around the capital of Scotland, the country where I happened to be born but continue to live as a matter of choice. No one could come away from it without knowing it was written by a Scot, said Alex Callinicos of my book How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions? I would perhaps put this slightly differently. I have always assumed that a grounding in the local and specific is a necessary precondition for understanding the global and general, and have therefore taken as a starting point for understanding the characteristic features of our epoch the ways in which they have affected Scotland. These features include the consolidation of neoliberalism as the dominant form of capitalist organization, the emergence of secessionist nationalism as a phenomenon of the developed world, and the decline of social democracy as the expression of working-class reformism. It is appropriate, then, that in addition to chapters assessing the impact of the Highlands on the work of Marx and Engels, and the influence of Gramscis writings over the Caledonian left, this volume should include discussion of three Scottish thinkers. Two of these are from Fife (Nairn himself from the village of Freuchie and Smith from the nearby metropolis of Kirkcaldy), and one from Glasgow (MacIntyre).

The essays reproduced here differ from the originals in five main ways. First, in keeping with my publisher Haymarkets location in Chicago, I have rendered the language into North American. This is a painless process that largely involves changing the letter s into the letter z in certain words, changing the word which into the word that in certain sentences, andas in the case of this sentenceadding a comma before the word and prior to the last item in a list. I have retained my Scotticisms (of which outwith seems to cause particular bewilderment in copy editors). Second, I have made the layout and endnotes stylistically consistent. Third, I have excised references to the publications in which the essays first appeared (of the as has been argued previously in International Socialism ... or readers of Historical Materialism will be familiar with... type). Fourth, I have removed passages that appeared in more than one essay except for the essay in which they first appeared (or in some cases except from the essay in which they seemed most appropriate) and replaced them with a see chapter x in this volume reference. Fifth, I have restored some passages that editors originally omitted, either because they disagreed with them on theoretical grounds ormore usuallybecause the article would otherwise have simply been too long for the publication concerned. Chapter 13, on Adam Smith, has the majority of these restorations. Excisions on grounds of taste, decency, or to prevent the publishers being bankrupted in a libel court have not, however, been reinserted. I have resisted the temptation to revise texts or add new material; anyone sufficiently motivated to check back against the originals would therefore be able to confirm that previously unpublished additions contain no references that post-date their appearance. Neil Rafeek predeceased the publication of his book, but three of the other authors discussedHobsbawm, Victor Kiernan, and Neil Smithhave died since I wrote the chapters dealing with their work, the last-named at a tragically early age; nevertheless, here too I have retained the original text in which they appear in the present tense.

Only in the case of chapter 6, on MacIntyre, is the text significantly different from previously published versions. This is a combination of several piecesor more precisely, a reconstruction of one original piece of research, which I subsequently parceled up into several different chapters and papers. I had been working off and on since 2000 on an edited collection of MacIntyres Marxist writings for the Historical Materialism book series. Around 2003 Paul Blackledge, who had independently discovered these works, joined me in the project at the instigation of the series editors, who for some reason suspected that it might otherwise never be completed. Paul has subsequently written extensively on MacIntyre and, while our views are not identical, they are compatible. A few brief passages from our jointly written introduction to Alasdair MacIntyres Engagement with Marxism , reproduced in this chapter, are actually Pauls, but it would have been pointless to rewrite sentences with which I was in basic agreement, even if it were possible to disentangle our respective contributions at this late date. I am grateful to him for permission to reprint such passages here.

Any assessment by a Marxist of other Marxists involves a particular standpoint within the tradition. As chapters 11 and 12, which deal with aspects of Stalinist organization and historiography, make clear, my standpoint is that of Trotskyism; but to self-identify in this way still leaves many questions unanswered, given the notoriously fragmented nature of that movement. Chapters 4 and 6 respectively discuss Deutscher and MacIntyre, two figures who, between them, demonstrate how one can arrive at different, not to say diametrically opposed, positions while ostensibly starting from the same body of work. MacIntyre declared that he could no longer consider himself a Trotskyist or indeed a Marxist of any sort by 1968. Deutscher remained faithful to his own conception of Trotskyism until his death the previous year. Yet I would argue that the latter effectively made as decisive a break with Trotskys thought as the former, all the more misleading for being unacknowledged. In any event, my sympathies here are with MacIntyre-as-a-Trotskyist, since my own political formation was in the International Socialist (IS) tradition to which he adhered between 1960 and 1968, although in a very different period. I first encountered the IS eight years after MacIntyres departure, at the point when the organization was transforming itself into the Socialist Workers Party, through Rock Against Racism and then the Anti-Nazi League, whose great achievements I discuss in chapter 5.

Next page