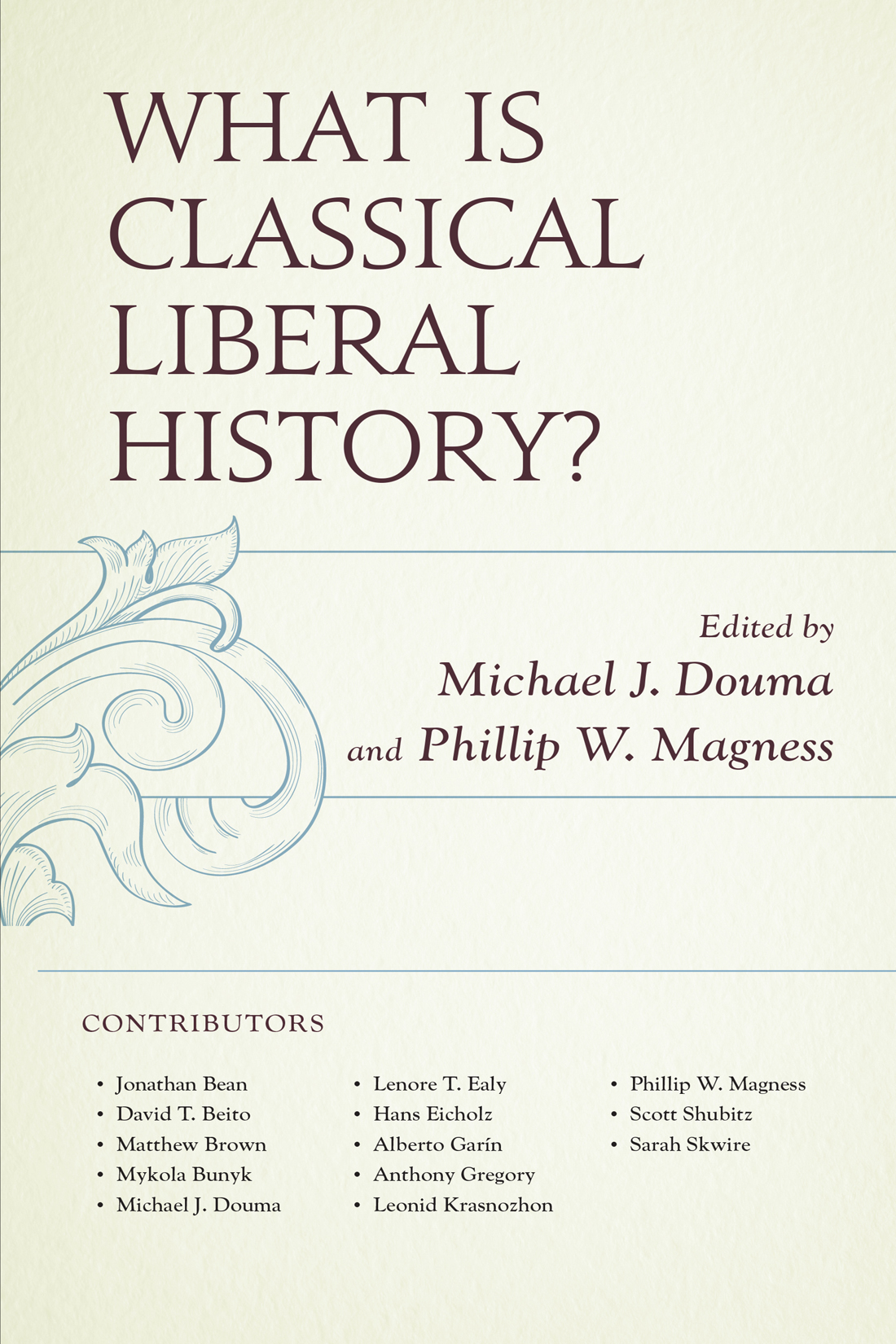

What is Classical Liberal History?

What is Classical Liberal History?

Edited by

Michael J. Douma and Phillip W. Magness

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2018 by Lexington Books

Chapter 1: Portions of this chapter were originally published as Scott M. Shubitz, Liberal Intellectual Culture and Religious Faith: The Liberalism of the New York Liberal Club, 18691877, The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 16, no. 2 (April 2017): 183205.

Chapter 7: A portion of this chapter was previously published in Jonathan Bean, Introduction, in Race and Liberty in America: The Essential Reader , ed. Jonathan Bean (University Press of Kentucky, 2009): 112.

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4985-3610-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4985-3611-0 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Michael J. Douma

Scott Shubitz

Phillip W. Magness

Anthony Gregory

Lenore T. Ealy

David T. Beito

Jonathan Bean

Hans L. Eicholz

Sarah Skwire

Leonid Krasnozhon and Mykola Bunyk

Matthew Brown

Alberto Garn

The editors would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided invaluable comments on early drafts of the book and the editors at Rowman & Littlefield who were a pleasure to work with. Michael Douma would like to thank Bruce Caldwell, Peter Boettke, Fred Smith, and George Nash for useful comments.

Jonathan Bean would like to thank all those who reviewed and commented upon earlier drafts, including David Bernstein, Richard Epstein, Robert Weems, Paul Moreno, Roger Clegg, and Andrew Barbero. I am also grateful for my loving wife, Tina Bean, who supported me in this endeavor, even as my keyboard clicking filled the air with words that eventually landed on these pages.

Hans Eicholz would like to thank his friends and colleagues, historians G. M. Curtis and Peter Mentzel for enduring his interminable discussions on these themes through the years. He would also like to acknowledge the assistance of his former mentor, the late Joyce Appleby who had commented on and encouraged an earlier essay on historicism and a review of Bernard Bailyn's work that proved highly informative in this project.

Lenore T. Ealy would like to thank the dozens of intrepid individuals who have participated since 2001 in the programs of the Project for New Philanthropy Studies, the Fund for the Study of Spontaneous Orders, and the Philanthropic Enterprise, initiatives founded by Richard Cornuelle (19272011) to foster scholarly deliberation to help us understand voluntary social processes as well as market processes.

Michael J.Douma

This book is designed to generate new ideas and new ways of thinking by reviving a neglected historical tradition, classical liberal history. In doing so, we hope not only to call attention to the best elements of the classical liberal tradition but also to call upon historians to reflect on the importance of this tradition to the history and practice of their own discipline.

Modern historiography reflects a diverse and overlapping set of epistemological positions, methods of inquiry, and approaches to research. In American academia, historiography began in a conservative vein. Conservative historians tend to write histories of nations and biographies of statesmen and great figures who serve as moral models for preserving the best of society. Conservatives see in the past a morality tale and lament the destruction of ordered systems which they hope to resurrect at least in part. By the turn of the 20th century, however, progressive history had come to dominate the preparation and practice of American historians. This approach to historical study arose toward the end of the 19th century, alongside the development of the new social sciences. Progressive historians, like their counterparts in sociology, political science, and economics, tended to see the role of their professions as helping to direct society on a path toward a better future. Such presentist and political purposes have also characterized the alternative Marxist and other collectivist models of history (e.g., feminist histories) which are based on the propositions that all people belong to a class, that their actions are shaped by their material circumstances, and that therefore we must study people as groups to understand how the past is necessarily moving us through different stages of development. More recently, postmodernist historians have challenged the possibility that historians can arrive at objective facts with the implication that history is itself a political act written only to serve power.

This book seeks to offer an alternative approach by illuminating what may be called classical liberal history. Like progressive, Marxist, feminist, postmodernist, or conservative historians, historians self-consciously working in the classical liberal tradition seek evidence from the past to explain how the world is structured. Unlike these other approaches to historical research, however, classical liberal historiography is based upon the principle of methodological individualism central to the classical liberal tradition. While classical liberal historians do not reject out of hand the study of nations, political parties, social or minority groups, they recognize that these collectives do not act on their own, but consist rather of the ideas and actions of their individual members. Classical liberal history is the study of individual action in the past. Guided by a general set of assumptions about human nature (i.e., that humans seek to better their circumstances, that they act on their subjective desires to satisfy ends, that they inhabit a world of trade-offs and scarcity) classical liberal historians see acting individuals as the basic units of historical investigation. Classical liberal history begins with the recognition of the inherent worth of the individual and presents individuals as the starting point for historical inquiry and concern. Moreover, because in the classical liberal tradition human action is conceived of as voluntary action, classical liberal historians are especially attuned to examining the economic, social, political, and cultural conditions, and institutions that preserve the widest sphere for human liberty.

Classical liberals have no monopoly on the study of liberty nor its definition, but they do give exceptional weight to liberty as a concern of their analysis and they do define liberty in ways that differ from the conservative or progressive conceptions of the term. In short, classical liberals value negative liberty over positive liberty. Negative liberty is best defined as freedom from external impediments deliberately imposed.and to understand the economic, political, social, and cultural limitations to complete, unlimited freedom.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.