Introduction

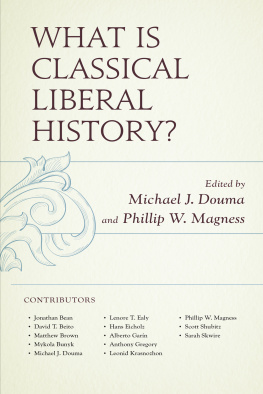

This reader contains a carefully selected collection of writings on historical methods and the philosophy of history penned by liberal historians.

What do we mean by liberalism or liberal history? It seems that every scholar in the social sciences would like to define liberalism in his or her own way. Certainly, plenty of room exists for differences of opinion on this matter. But defining any -ism requires circumscribing a set of beliefs, or drawing lines in such a way as to connect ideas that we believe form a coherent tradition.

A common path toward defining liberalism, for example, is to list thinkers for whom there is general agreement that they fit the tradition: Benedetto Croce, Thomas Jefferson, Immanuel Kant, John Locke, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Paine, Max Weber, and so forth. Generally, however, this list includes social thinkers, political theorists, and economists but neglects historians and the historical writings of such polymaths as David Hume or Wilhelm von Humboldt, who are included for their other, nonhistorical contributions. For this reason, existing works on the history of liberalism are typically of little value for understanding the liberal approach to the past.

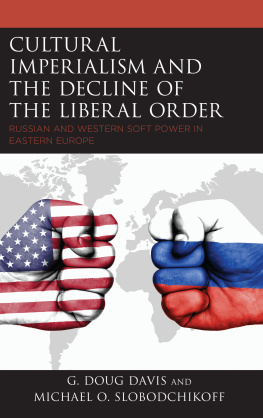

Liberal history is primarily concerned with ideas and with the reasons why individuals acted as they did in the past. Liberal historians prefer to study themes of power and liberty, particularly as they relate to the rise and fall of political systems that protect liberties and individual rights. In the 19th century, liberals proposed various stadial theories of history, which were often based on race and geography. These early liberals shared a belief that liberty was emerging in history, and some even thought that this pattern was natural and unstoppable. Liberal historians in the 20th century, however, generally took the opposite position, rejecting historical inevitability and any grand scheme of history. They also abandoned deterministic theories of race and geography. From a certain perspective then, a discontinuity exists in what constitutes liberal theorizing about history.

The writings collected here indicate, however, that self-identified liberal historians from the 19th century to the present day have held fairly consistently to a core set of positions in the methods and theory of history:

1. The belief that historical writing should aim to describe reality, that a real world existed before and outside the mind of the historian, and that evidence of this world can be reliable for producing historical accounts.

2. The view that historical knowledge is different from the knowledge of the natural sciences and social sciences, and that history is an autonomous discipline, with its own methods.

3. An opposition to proposed laws of history and any kind of historical determinism that devalues the free action of individuals. Liberals prefer instead a historicism that supports the uniqueness and incommensurability of each historical event, culture, or period.

4. The rejection of sociological concepts as actors, that is, nations as agents or abstractions such as the Volksgeist being responsible for historical change.

The first pointessential to the liberal view of historymight be confused for a universal premise of modern historiography, but that owes something to the influence of liberal thought on mainline Western historical thought. Not every historian aims to describe reality through the evidence. Some schools of historical thought explicitly reject that such a thing is possible, or even desirable. Some historians revel in paradox or esotericism, or they deny that historical writing can ever present a true description of the real world. History, they say, is nothing but a language game that we play to give power to one group or person over another. History, in this view, is a form of politics.

On the second point, this reader indicates that the anti-scientific strain of liberal history has always been quite strong, even if it has appeared in different guises. One problem here is that the adjective scientific applied to historical methods has multiple meanings. In one instance, it means a spirit of accuracy, thorough observation, and rational argumentation with professional standards. No liberal historian (or modern historian of any kind I suppose) opposes that kind of scientific history. But liberals have taken issue with the idea that history is a protoscience, and that, like physicists, historians can deduce a set of laws from observations.

Before scientific history was the old tradition of literary history, or history as an art, which required imagination and creativity; its purpose was education and moral insight. This view was still the school of Lord Acton and his followers like G. M. Trevelyan, whose essay Clio, a Muse related its history. Trevelyan contrasted this school of thought with the new, scientific history: There is no utilitarian value in knowledge of the past, he wrote, and there is no way of scientifically deducing causal laws about the action of human beings in the mass. In short, the value of history is not scientific. Its true value is educational. It can educate the minds of men by causing them to reflect on the past.

In 19th-century Germany as well, liberal historians defended the independence of history from science by defining history as a part of the Geisteswissenschaften, or human sciences. At issue was whether historical understanding was something different from scientific explanation. Liberals argue, then and now, that human behavior cannot be explained and is not predictable in the scientific sense because humans have free will, they respond uniquely to each circumstance, and there is no path toward replication.

The most influential thinker in this regard was the German Wilhelm Dilthey, who argued that the aim of the human sciences was not to isolate actions as examples of a universal law, but to understand the relationship between the part and the whole, or, as historians might phrase it, the event in context. Combined with the view that one could not isolate historical facts and treat them as separate abstract instances of natural laws, Dilthey defended the historicist view that experience and even rationality are conditioned by historical circumstances.

The debate about the autonomy of history is at the root of the divide between mainline liberal historicists and many of the 20th-century social science historians inspired by sociology, Progressivism, and Marxism. Left-liberals influenced by anthropology more than Comtean sociological or logical positivism, however, tend to also defend a version of historicism, wherein they emphasize the uniqueness of each culture and individual, as well as the uniqueness and irreproducibility of historical events.

As the selections in this reader show, the liberal approach to the past is generally skeptical of laws of history and suggestions of historical determinism, noted above as the third point. Liberalism is a wide tradition, and it must be noted that there are examples of liberalslike the father of scientific history, Henry Thomas Bucklewho sought laws of history. Those who defend causal laws of history sometimes argue that we come to historical explanations by seeing them as particular instances of general laws. Yet this appears to be a distinctly minority position among liberals. In fact, it is precisely on this point of laws and determinism where many a liberal will fall or stand. Sidney Hook, for example, switched from being a communist to a social democrat, partly, as he explains in his book