First published 2018

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2018 Taylor & Francis

The right of Michael J. Douma to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-1-138-04883-6 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-04885-0 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-11284-8 (ebk)

Typeset in Goudy

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

I want to claim my ideas as my own, but Im certain that most of the time my ideas did not begin with me. The truth is, a historian can never cite all of their sources. Much about the way a person interprets the world is shaped by their experiences in childhood. By middle age, theyve experienced too much to remember where they first encountered an idea. Wherever my ideas came from, I know they were shaped in discussions with friends and family, and with students and colleagues.

Many of the ideas in this book I have presented in lectures on American history at Florida State University, the University of Illinois-Springfield, and James Madison University. I have also presented them in guest lectures in a dozen other places. Because I am trained in the history of the United States, most of the examples in the book come from American history, rather than say European, African, or Asian history. This is an accidental feature of the book, whose true aim is not to explain American history per se, but to explain something about the discipline of history itself.

In choosing to write about history, I owe a great debt to those who have come before, but I also owe it to the readers of this book to not just repeat what others have written. Many books on the nature of history and historical thinking explain the development of historical study and the successes and failures of its various theories. Today, an absolutely astounding number of new publications on history appear each year, and many of them are quite good, but only a few of these books show the creative side of history. To me, this is a great problem. I see history as a creative and engaging art, and I want others to view it this way as well.

Practical history research guides typically include short sections covering epistemology (the philosophy of knowledge) and historiography (historical views of history). But the main purpose of most of these books is to serve as manuals for students who are thinking about historical research for the first time. These texts march students through terminology and the specific steps of research, analysis, interpretation and writing. With few exceptions, however, they remain detached and uninspiring.teacher in a classroom, explaining how to drive a car by going over the function of the gas pedal and brake, the turn signal, and the gas gauge. The only way you can really learn to drive is from experiencing the feel of the road.

Likewise, I think that historians are made in libraries and in the archives, and I believe that research guides are of little value if they treat historical research skills as a boxed good, independent from actual historical practice. A good history book is one that inspires its readers to get to work doing history. Young historians should learn from the examples of their teachers and share in their curiosity and passion for history, but if they are to think like historians, they need to develop their own stride and their own voice.

I respect my own great teachers, and foremost among them Bill Cohen and Bob Swierenga. My inspirations also include the physicist Richard Feynman, who encouraged us to confront conventional wisdom and to look at the world from a new point of view, and the comedian John Cleese, whose lecture on creativity has been a motivating force for me. I dedicate this book to the young scholar who is looking for answers. I welcome correspondence from readers of this book, and I will do my best to respond to any questions about history or the history profession.

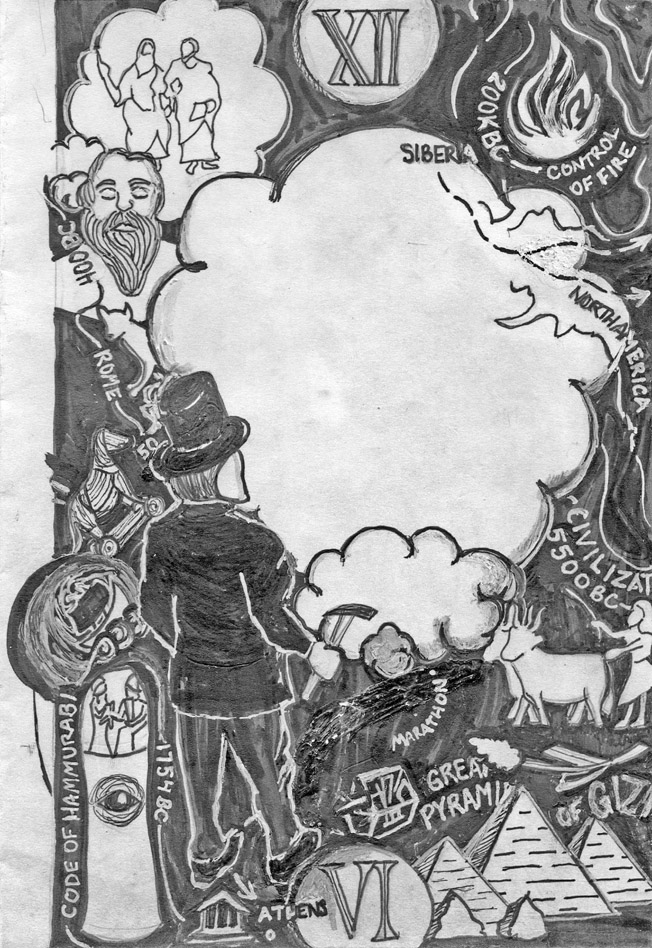

Ive had many discussions that have helped this book develop. Thanks to Trevor Burrus, Daniel Moseley, Bill Glod, Lael Weinberger, Rob Faith, Hans Eicholz, Scott Shubitz, Kevin Currie-Knight, Michael OLeary, Suzanne Sinke, Richard Cytowic, Frederick Turner, Michael Watson, Herman Paul, Christopher Griffin, Todd Zywicki, Jason Brennan, Lauren Brennan, Marian Eabrasu, Carson Young, Lydia Ingram, and Anders Bo Rasmussen. I thank Sloane Shearman for the art in Figure 0FM.1, Xavier Macy for images in the book, and Martha King for work on the index. I thank my Facebook feed for the many comments and leads on my historical musings. Thanks also to Gracie Pater, Pascal Bandoch, Henry P. Bigfellow, and everybody named Kevin. There would be a lot fewer Kevins without you. For inspiration, Id like to thank D.J. Wolffram, Chris Arndt, Richard Bell, and Peter Boltuc.

Making history is a personal exercise, and some would even say that all history is really just autobiography, since we are always projecting our own experiences onto the past. For these reasons, among others, I make no apology for the personal nature of the content to follow or for the use of the personal pronoun I.