Contents

Page List

Guide

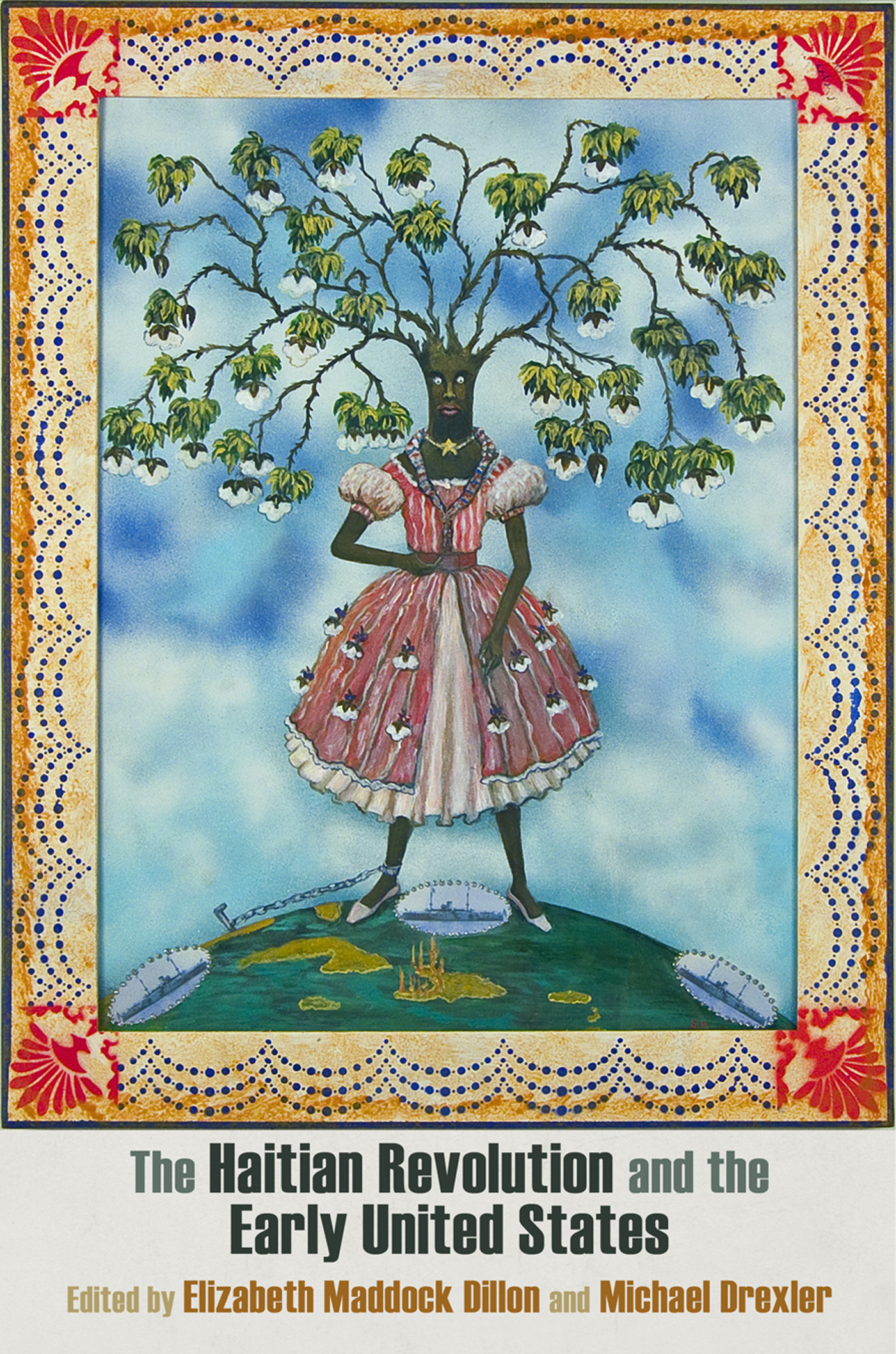

The Haitian Revolution and the

Early United States

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series editors:

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown,

Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

THE HAITIAN

REVOLUTION

AND THE EARLY

UNITED STATES

Histories, Textualities, Geographies

Edited by

Elizabeth Maddock Dillon

and

Michael J. Drexler

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2016 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-4819-7

CONTENTS

Elizabeth Maddock Dillon and Michael J. Drexler

Carolyn Fick

James Alexander Dun

Duncan Faherty

Ivy G. Wilson

Laurent Dubois

David Geggus

Cristobal Silva

Kieran M. Murphy

Edlie Wong

Colleen C. OBrien

Michael J. Drexler and Ed White

Gretchen J. Woertendyke

Sin Silyn Roberts

Peter P. Reed

Marlene L. Daut

Anthony Bogues

Introduction

Haiti and the Early United States, Entwined

ELIZABETH MADDOCK DILLON AND MICHAEL J. DREXLER

It should no longer be possible to write a history of the early republic of the United States without mentioning Haiti, or St. Domingue, the French colonial name of the colony known as the pearl of the Antilles and the site of a world historical anticolonial, antislavery revolution that occurred between 1789 and 1804. In repeating this, we join a distinguished cohort of writers who have made similar claims in the past, though historically, such claims have tended to rise to the fore only to recede beneath subsequent waves of amnesia. Today, Haiti is known, in the words of Haitian poet and historian Jean-Claude Martineau, as the only country in the world with a last nameHaiti, poorest country in the western hemisphere. This tendency to place Haiti out of relation to and in isolation from other cultures and histories masks a deep history of connection between Haiti and a host of other countries. Unquestionably, Haiti bears strong historical ties to France, but the countrys relation with the United States has been historically decisive as well. Moreover, the United States has, in turn, been shaped in cultural and political terms by its Caribbean neighbor. It is this early and far-reaching history of mutually entwined relations between Haiti and the United States that we explore in this volume.

Haitian exceptionalism has its double in American exceptionalism, a doctrine that holds that the United States embodies the world-exceptional origin and purest form of political liberty and democracy. While this doctrine still holds sway in contemporary popular political debate, it has been widely criticized in the field of American studies in recent decades. Nonetheless, it is fair to say that these twin exceptionalismsone superlatively negative and the other superlatively positivewield considerable force in the popular imagination of Haiti and the United States today. This polarization of the United States and Haiti has substantive effects: it places Haiti conceptually far, far away from the United States, thereby erasing both the geographical proximity of the two states and their historical and political contiguity and interrelation.

In contrast to this image of two distinct and unrelated societies with disparate histories, let us conjure two prosperous eighteenth-century colonial societiesFrench St. Domingue, and British North Americamarked by compelling similarities to one another. In fact, the political histories of the two colonial societies are remarkably parallel for a period of time. At the close of the eighteenth century, colonists in both locations began to find exclusion from metropolitan seats of political power increasingly burdensome. No taxation without representation is a phrase that might be understood to have launched the Haitian Revolution as surely as it did the American Revolution that preceded it. In the case of the North American colonies, British colonials were rebuffed by the English Parliament in their attempt to achieve representation there, precipitating outrage and, eventually, armed insurrection against British colonial rule. In the case of St. Domingue, French colonials demanded representation in the French Estates General in Paris in 1788amidst the political ferment of the French Revolutionand were, in contrast to North American British colonials, granted this right. But together with the right to representation in the French metropole came a second question: Which inhabitants of St. Dominguewhite, black, mixed race, free, enslaved, and/or property-owningwould count as the citizenry of the colony? It was over this question that violence first erupted in St. Domingue, marking the beginning of a revolution that lasted from 1789 to 1804a revolution that eventually succeeded, like the American Revolution, in throwing off colonial rule.

At the very moment when French colonials secured the right to representation in the Estates General, Honor Mirabeau, a prominent French statesman, underscored the contradictions inherent in a political system that operated on a principle of democratic representation while countenancing slavery. According to C. L. R. James, Mirabeau attacked the logic of the slaveholding proprietors of St. Domingue who sought representation for themselves and denied it to free and enslaved blacks: You claim representation proportionate to the number of the inhabitants. The free blacks are proprietors and tax payers, and yet they have not been allowed to vote. And as for the slaves, either they are men or they are not; if the colonists consider them to be men, let them free them and make them electors and eligible for seats; if the contrary is the case, have we, in apportioning deputies according to the population of France, taken into consideration the number of our horses and our mules? Two aspects of Mirabeaus speech are worth noting: first, he succinctly points out that slavery operates by what we might call a differential distribution of the humanthat is, some humans count as human, and others do not, or they count in different ways, as, for instance, animal bodies rather than voting citizens. In so doing, he reveals a core aspect of European colonialism: the uneven and racialized distribution of humanity across white, black, and indigenous peoples. Second, we might note that Mirabeaus critique of the contradiction between democracy and slavery is one that the United States faced at the same historical moment: in 1787, during the drafting of the U.S. Constitution, statesmen grappled with precisely the question of how to enumerate whites and blacks in apportioning representational power to the states. The problem of how to count citizens and dis/count slaves was infamously resolved in the case of the U.S. Constitution by enumerating disenfranchised slaves as three-fifths of a person. At the moment of revolution, then, white colonials and free and enslaved blacks in St. Domingue and British North America confronted precisely the same situation: how to reconcile the development of modern doctrines of universal political liberty and equality with the economic engine of modernitynamely, a colonial system of labor and production premised upon dehumanizing practices of race slavery.