Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund.

Copyright 2015 by Hasia R. Diner.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Times Roman and Perpetua display type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Diner, Hasia R. author.

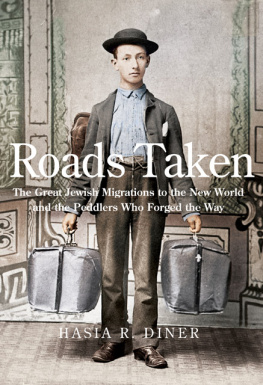

Roads taken : The great Jewish migrations to the new world and the peddlers who forged the way / Hasia R. Diner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-17864-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. JewsEconomic conditionsHistory. 2. Jewish peddlersHistory. 3. Jewish businesspeopleHistory. 4. JewsMigrationsHistory. I. Title.

DS140.D56 2015

381.108992407dc23

2014022369

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Hannah and Abraham

To Anh

To Emmanuel

Welcome to my world!

You road I enter upon and look around, I believe you are not all that is here, I believe that much unseen is also here

Walt Whitman, Song of the Open Road

Contents

Preface

Roads Taken tells a story about a mass of ordinary people who in their ordinariness made history. The immigrant Jewish peddlers and the non-Jewish women to whom they sold come across here as actors in a vast historical drama which transformed both the Jewish people and the countries to which they immigrated by means of this prosaic, indeed pedestrian, occupation. A nearly ubiquitous figure on multiple continents around the new world, the itinerant Jew, weighed down by a pack on his back or sitting behind a horseno doubt as exhausted as himselfwent house to house, farmstead to farmstead, mining camp to mining camp, and plantation to plantation, selling consumer goods to customers, one by one. These peddlers, newcomers from Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and North Africa, envisioned their peddling as a transitional phase in their lives, one that linked their lives in the homes they had just left and settling down in some new place.

Roads Taken may take as its subject a not particularly heroic or glorious chapter in history, but it allows its subject, peddling, to do some heavy work. It challenges the overwhelming tendency in Jewish history to emphasize antipathy to the Jews as the most powerful engine, which drove all developments. The migrations to all these new lands cannot be explained fully by the conventional and worn-out explanation of anti-Semitism, anti-Jewish violence, or pogroms. Rather, the beckoning of newly opened territory for commerce in widely scattered places more powerfully pulled them out of their old homes than did persecution push them out.

My Jewish peddlers did not fall back on this classic Jewish occupation because the hostility of the larger world precluded engaging in other pursuits. They opted for it because they calculated that it provided them with the shortest and most efficient path to fulfilling the goals of their migration, namely economic advancement, marriage, family reunification, and achieving what they considered a good life. They did not turn to other Jews for credit because banks and other lending institutions harbored negative views of Jews. While bank presidents in fact might have not liked Jews, the Jewish peddlers had no interest in going to non-Jewish credit sources. They preferred to turn only to other Jews.

The experiences of the peddlers also chips away at some of the prevalent ideas in the scholarship and Jewish collective memory about peddlers. Jewish peddlers did not lack skill. Although they did not run machinery, make tools from iron, or build furniture, they knew or learned languages, developed accounting systems, and figured out where the best opportunities existed. They developed interpersonal communication skills, mastering the art of how to approach a variety of customers. The peddlers had to sharpen what the twenty-first century has defined as their people skills.

So, too, new-world Jewish peddlers had more in common with one another than they differed based on where they came from. The notion that German and eastern European Jews underwent essentially different experiences falls by the wayside in the face of their shared peddler histories. The division of world Jewry into Ashkenazicthat is, Europeanand Sephardic, or Spanish-derived, halves fades on recognizing how peddling brought both to the Americas, the British Isles, and southern Africa. While they may have formed separate synagogues and communal bodies in Atlanta or in Havana, their new-world experiences took their shape from the fact that both took their first footsteps in these places as peddlers.

Finally, Roads Taken asks scholars of the many places to which Jews went through the aegis of peddling, to think about Jewish history as crucial to the histories of the United States, Canada, Mexico, Cuba, Wales, Jamaica, Argentina, Australia, Ireland, and so on. The experience of Jews in these places merits more than a paragraph or two, at the most, nor should it be considered to have been independent of or tangential to local and national developments. Rather, despite the relatively small number of Jews who may have migrated to these countries, and the various regions within, Jews furthered colonial developments and the exploitation of land for European expansion. The material goods that Jews brought to the women and men who did the basic work of the societyfarming for themselves or laboring on the

In Roads Taken I look at the entirety of the new world, obviously offering only a bird's-eye view. But despite my global focus, much of my attention centers on the United States. Of the Jews who made up the foot soldiers of the great Jewish migration, more than 80 percent came to America. Of the 20 percent who did not, many wanted to, and some eventually did. The United States, more than any other place, matters in this history of peddling and the history of Jewish migration in the modern period. It offered Jewish immigrants a bundle of rights, political and economic, which could not be matched anyplace in the new world. The level of civic integration and religious innovation exhibited by the former peddlers who chose America had no new-world equivalent. Indeed, the experience of Jewish immigrant peddlers in America provides ringing endorsement of American exceptionalism, a concept much discredited by American historians, but one that reclaims its vitality when we investigate the experiences of the Jews.

The road functions as the central metaphor of this book, providing its intellectual core as well as its title and those of its chapters. That metaphor takes readers on a journey back to the points where and when Jewish peddlers got on the road, and down political, communal, and personal paths to where those roads took them. It evokes life on the road, with each vignette or narrative, each story about an individual or a place, a paving stone on the path toward the ultimate goal, which for the peddler meant crossing the road and getting off of it for good. The roads here connected Jewish peddlers to the homes of potential customers and led them to hubs of Jewish life.

Next page