Preface

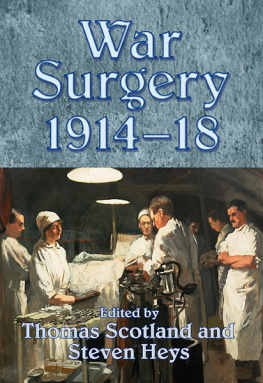

The history of warfare and the history of medicine have long been intertwined. Hippocrates of Kos, the ancient Greek physician who is generally considered the founder of Western medicine, even counselled aspiring young doctors to follow war as the only proper training for a surgeon. I understand this remains so today for trauma surgery.

During the twentieth century, wars resulted in many advances in medical treatment and surgery. Modern weaponry became more destructive and medical techniques and procedures were developed to deal with the massive scale and changing nature of battlefield casualties. A paradox also emerged: as war grimly expanded the opportunities for clinical research and the application of scientific discovery, developments in preventative medicine also increased the effectiveness of fighting forces through improvements in soldiers health and disease resistance.

The major wars of the last hundred yearsfrom the First World War to the recent and current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistanhave driven advances in treatment for wounds and pain management, and more effective preventative measures against disease and infection. New approaches have been developed to evacuate, treat and heal the injured and wounded. Nevertheless, war continues to inflict its toll of carnage and human misery on not just combatants but also civilians who are, too often, either the intended or accidental targets of modern conflicts.

For veterans, and their families too, the post-war legacy of combat experience can sometimes seem as severe and persistent as the effects of wounds and injuries. The war-damaged soldier became a conspicuous figure in the aftermath of the First World War as repatriation agencies worked to alleviate the suffering of invalided veterans, to allocate appropriate pensions, and to introduce the first struggling medical recognition of the symptoms of deferred, posttraumatic stress.

In many respects, modern military medicine must remain equally concerned with treating the consequences of military service on veterans health as with treating soldiers during their service.

These and many other aspects of the interaction of war and medicine are the primary themes of this volume. All the chapters were originally presented at an outstandingly successful international conference, War Wounds: medicine and the trauma of conflict, convened by the Australian War Memorial in September 2009 with the support of the Department of Veterans Affairs and the involvement and interest of the Minister, the Honourable Alan Griffin MP, who kindly opened the event.

This conference attracted an eclectic and, as it turned out, dynamic mix of historians, medical practitioners, military medical officers, medics, nurses and veterans who explored the myriad experiences of casualties in war, their impact and aftermath, from their different perspectives. The event aroused considerable interest among the military, the public and the media, and undoubtedly led to a heightened general awareness of this important area of military-medical history.

Many moving personal stories also emerged as the lessons of the past served to illuminate problems of the present and to enhance understanding of veterans issues and the enduring impact of war on Australian society.

The conference was originally conceived by Ashley Ekins, Head of the Memorials Military History Section, who, with his colleague Elizabeth Stewart developed the program and jointly compiled and edited this collection. Each of them also contributed a chapter based on their own particular research interests. I acknowledge their dedication along with the contributions of the many fine scholars who participated in the conference and collaborated in the production of this book.

A number of other people contributed their skills and efforts. In particular, I thank Ian Watt and Benny Thomas and their team at Exisle Publishing for once again producing a high-standard publication that the Memorial is proud to sponsor. Among Memorial staff, Ron Schroer expertly administered the publication arrangements, editors Robert Nichols and Andrew McDonald edited the diverse collection of papers to the publishers requirements, and Aaron Pegram of the Military History Section researched photograph collections and wrote many of the captions. Diane Lowther compiled the index.

Every effort has been made to locate current holders of copyright for text and illustrations reproduced here but we apologise for any omissions and would welcome information to enable amendments to be included in future editions.

One notable contributor was Professor Simon Gandevia who discussed his fathers experiences as a regimental medical officer with an Australian infantry battalion in the Korean War. He also announced a generous family bequest to the Memorial to establish the Bryan Gandevia Award, an annual military history award in his fathers name, to foster research among junior scholars into significant areas of military-medical history.

That award, this book, and the conference that inspired it, has demonstrated once again the Australian War Memorials commitment to historical research and to maintaining the Memorials pre-eminence as one of the finest research facilities in the world. As Professor Jay Winter of Yale University graciously noted in the introduction to his fine keynote address to the War Wounds conference:

It is right and proper that we speak of a subject of the importance of war wounds here at the Australian War Memorial. This is where serious reflection on the Great War happens. Yours is a unique institution, braiding together the emotive power of a shrine, the representational power of a museum, and the scholarly riches of a great archive. After over 40 years of working in this field, I can say with some confidence that the Australian War Memorial is the premier centre for First World War studies in the world today. It enables scholars and laymen to come together in an act of recognition, the recognition that the Great War shaped the world in which we live.

Professor Winters incisive comments might be applied to all major wars. His words should inspire and encourage future generations of scholars and soldiers not to forget the lessons of history.

Steve Gower

Director, Australian War Memorial

May 2010