Cover

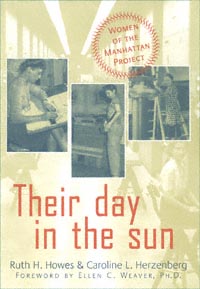

| title | : | Their Day in the Sun : Women of the Manhattan Project Labor and Social Change |

| author | : | Howes, Ruth.; Herzenberg, Caroline L. |

| publisher | : | Temple University Press |

| isbn10 | asin | : | 1566397197 |

| print isbn13 | : | 9781566397193 |

| ebook isbn13 | : | 9780585388816 |

| language | : | English |

| subject | Manhattan Project (U.S.)--History, Women scientists--United States. |

| publication date | : | 1999 |

| lcc | : | QC773.3.U5H68 1999eb |

| ddc | : | 355.8/25119/0922 |

| subject | : | Manhattan Project (U.S.)--History, Women scientists--United States. |

Page i

Their Day in the Sun

Women of the Manhattan Project

Page ii

In the series

LABOR AND SOCIAL CHANGE

edited by Paula Rayman and Carmen Sirianni

Page iii

Their Day in the Sun

Women of the Manhattan Project

RUTH H. HOWES AND

CAROLINE L. HERZENBERG

Foreword by

ELLEN C. WEAVER, PH.D.

TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Philadelphia

Page iv

Disclaimer:

Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the netLibrary eBook.

Temple University Press, Philadelphia 19122

Copyright 1999 by Temple University

All rights reserved

Published 1999

Printed in the United States of America

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Howes, Ruth (Ruth Hege)

Their day in the sun: women of the Manhattan Project / Ruth H.

Howes and Caroline L. Herzenberg; foreword by Ellen C.

Weaver.

p. cm. (Labor and social change)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-56639-719-7 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Manhattan Project (U.S.) History. 2. Women scientists United

States. I. Herzenberg, Caroline L., 1932- II. Title.

III. Series.

QC773.3.U5H68 1999

355.8251190922 - dc21 99-17683

CIP

Page v

Contents

| Foreword | vii |

| Prologue | 1 |

| 1 | The Great Scientific Adventure | 6 |

| 2 | The Founding Mothers: Pioneers in Nuclear Science | 20 |

| 3 | The Physicists | 35 |

| 4 | The Chemists | 67 |

| 5 | Mathematicians and Calculators | 93 |

| 6 | Biologists and Medical Scientists | 115 |

| 7 | The Technicians | 132 |

| 8 | Other Women of the Manhattan Project | 152 |

| 9 | After the War | 181 |

| Epilogue | 201 |

| Appendix 1: Female Scientific and Technical Workers in the Manhattan Project | 203 |

| Appendix 2: Chronology | 219 |

| References | 237 |

| Index | 253 |

| Photographs follow pages 60, 110, and 174 |

|

Page vi

Page vii

ELLEN C. WEAVER, PH.D.

Foreword

RUTH AND CAROL'S BOOK fills a very personal need for me.

I worked on the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, but I don't recall any other female scientists working in my groups, and I didn't get to know any of the women working elsewhere at the site.

One reason for this was, of course, that women were a small minority on the project. Another is that for security reasons, the various operations at Oak Ridge were spread out over the site and kept separate as much as possible. I met a couple of women in the locker room, where we changed into protective clothing, but we didn't form lasting friendships. My buddies were all men. Indeed, I'm ashamed to say that I occasionally heard men at Oak Ridge discuss female scientists in insulting terms concerning appearance, not competence but that I did not rise to their defense. I remember no sense of camaraderie among women; indeed, we viewed other women with some suspicion. The support that women give one another today did not exist then.

I had majored in chemistry in college, not out of any love of science but because I wanted a skill that would empower me to support my husband, a physicist, through graduate school. When he was spirited off to a secret project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, I followed as soon as was practicable. After a short stint cranking out calculations on those old Marchant calculators (talk about boring!), I was put to work in a lab with a real project of my own, and just loved what I was doing. Challenges came along daily; it was fun solving them and getting answers. I was only a bit player in the science of the Manhattan Project, but I was a player.

One task I was given was to find a way to shield the radiation of phosphorus-32. This was a beta-emitter, and lead bricks let radiation through. I made sandwiches of alternating lead and aluminum layers, but to test the effectiveness of various arrangements I had to assemble a Geiger tube. This was done by splitting mica under benzene with a needle, gluing a thin sheet of mica to the rim of the tube, evacuating the air from the tube, filling the tube with the appropriate gas mixture,

Page viii

and then calibrating it. Subsequent generations never really knew the joy of getting an instrument to work if they hadn't had some experience with the love and string and sealing wax that made it function. One of the standard pieces of advice I've given to young scientists especially women is to understand the insides of the instruments they rely on and to be able to troubleshoot them.

Later I worked with David Hume's group on devising methods for the quantitative analysis of fission products from the Oak Ridge graphite pile. Again, this was essentially research, and challenging. In addition, a number of the noted scientists on the project taught courses at Oak Ridge. One could get college credit for these from the University of Tennessee, at the bargain price of one dollar per semester hour! I took and passed quantum mechanics and vector analysis, but never tried to transfer the credits toward a degree.

It was an exciting time, and I regret that I met so few of the women who shared it with me (although in later years Mina Rees became a close friend). I'm thrilled to learn through Ruth and Carol's words about so many of the remarkable women who contributed to that great enterprise. This book lets us meet one another at last and to swap stories. The authors have done superb detective work, tracking down an impressive number of us more than 300.

When I read the personal reminiscences of the men who were nuclear pioneers, I'm struck by the importance they place on their friends and associates, and on the often intense interaction among them, which could lead to major insights in both the theory and practice of science. And I'm a bit jealous. By and large, women did not share in that give-and-take. Through this volume, I can vicariously share in it, and at least indulge in some might-have-beens.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984