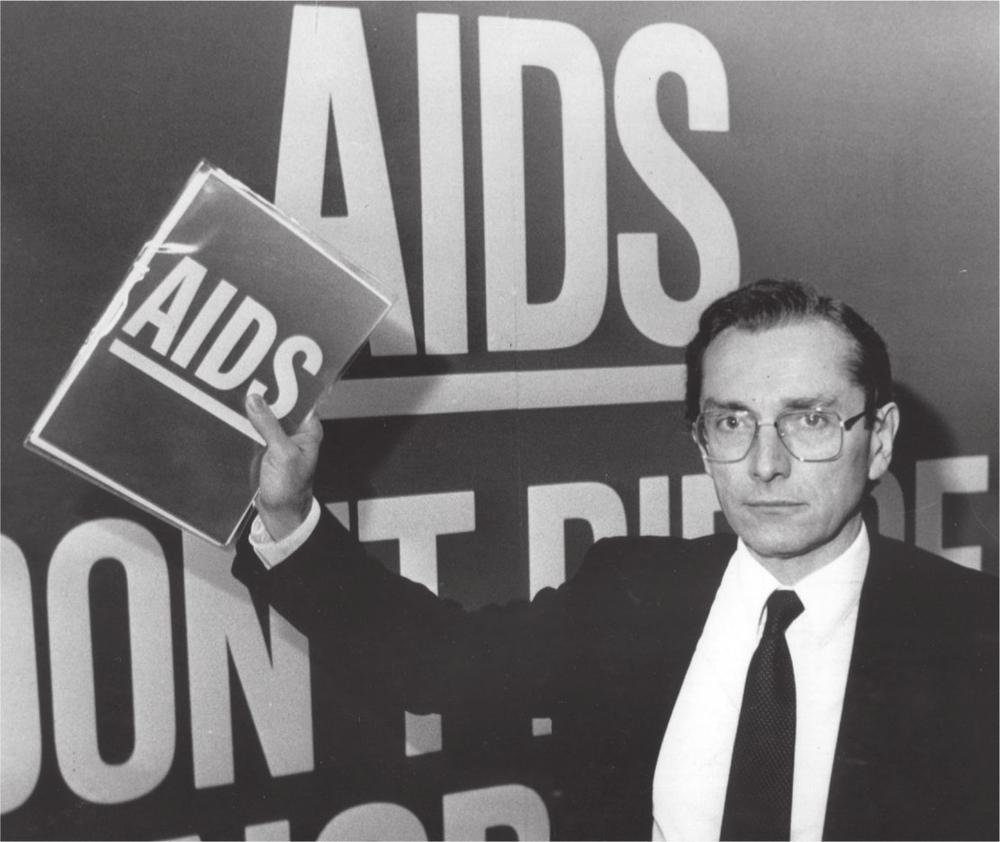

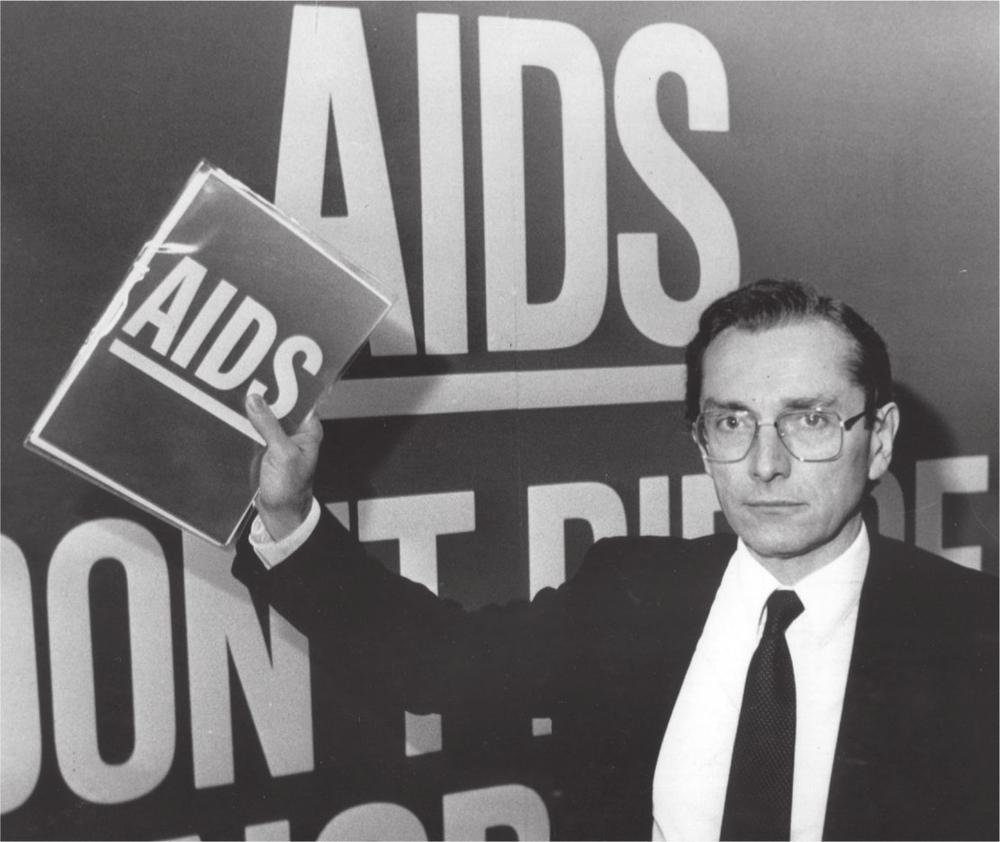

WHY IS THIS book called Dont Die of Prejudice? Almost thirty years ago I ran a campaign in Britain warning of the dangers of Aids called Dont Die of Ignorance. It was at a time when our knowledge was limited and there were no drugs that could be used to combat HIV, the cause of Aids. It was a death sentence. Young men and women filled the hospital wards around the world but there was nothing that the doctors and nurses themselves working under enormous strain could do to avert the developing tragedy. It was vital that the public were warned of the danger we faced. We needed to understand.

Today, much has changed. In particular, we now have drugs that can preserve life. Yet, in spite of the medical advances, there remains the scandal of over 2 million new infections a year and over 1.5 million deaths. Over thirty-five million people worldwide live with HIV. Ignorance of how to prevent HIV is still vast and in the absence of public education campaigns it has increased over the last twenty years.

Worst of all, today millions of men and women who are already infected do not know their condition and continue to spread the virus to others. They have not been tested, let alone treated. They may live in countries with undeveloped health systems; they may face long journeys to their nearest hospitals; or, worst of all, they may be the victims of prejudice, discrimination and stigma. Governments have made homosexuality a criminal offence in seventy-eight countries around the world. But that is a too convenient, blanket excuse.

All too often such laws are not condemned but supported by the public in those countries. The reaction of families and communities to any evidence that a person is gay or lesbian or is the victim of HIV is a huge deterrent to testing. The penalty for disclosure in many parts of the world is to be thrown out of the family home and out of work. Similar discrimination against sex workers, drug users and transgender people only adds to the tragedy . This prejudice encourages secrecy and facilitates the spread of HIV- and Aids-related deaths around the world.

MY INVOLVEMENT IN Aids began as the pandemic began to unfold. Between 1981 and 1987 I was Secretary of State for Health in Margaret Thatchers government, and Chapter One of this book looks back at what we did then, and the obstacles we faced. After leaving government I kept in touch with the progress of the efforts to halt the spread of HIV and Aids. I worked with voluntary organisations like the Terrence Higgins Trust and in 2011 headed a House of Lords Select Committee on HIV/Aids which examined the position in Britain (which I will return to in Chapter Ten). I remain Vice-Chairman of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on HIV and Aids and am currently also on the board of the International Aids Vaccine Initiative and the patron of the British HIV Association.

I do not claim that this short book covers every nation in the world or every issue. It is not an official report or an academic treatise. My intention is instead to report on some of the most important and urgent issues that nations are facing today. It is based upon visits to nine cities of the world between November 2012 and February 2014, ranging from the Cold War capitals of Moscow and Washington to the cities of the future like Cape Town and New Delhi. The undiagnosed certainly propel the figures in Africa and Asia but they do also in the United States and Europe. For once, we all face an issue which cannot be ignored on the basis that it is over there or out of sight in some distant land.

We now have antiretroviral drugs and the promise they give to patients of a full and active life. The prices have come down, cheaper generics have been introduced and all the patient has to do now is take one or two tablets a day rather than the cocktail of twenty drugs or more required a few years ago.

As far as drug users are concerned, the clean-needles policy has been proved effective and has been emulated by a range of countries. The trusty condom continues to show its worth in spite of some damaging attacks by people who must have known better, and male circumcision has been proven as a valuable means of preventing disease . We might not have a vaccine or a cure, but we have the means to at least contain the virus and yet the casualties continue to build up not just in their thousands but in their millions.

That is why for this book I wanted to find out more about what is happening, not only in Britain but in other countries around the world. For HIV and Aids is self-evidently an international epidemic in which around thirty-six million men, women and children have so far perished yes, thirty-six million. The drugs which will preserve life are now available, but still we have over 1,600,000 deaths a year. Surely we can do better than that? Surely there is a duty on us to preserve the lives that are being so squandered?

In the 1980s we had the excuse that we did not have the drugs to prevent death but what is the excuse today? There is no doubt about what has shocked me most on my travels. In a word, it is prejudice: the official and personal prejudice against minorities which stands today as a massive barrier to public health throughout the world.

Norman Fowler launching the Dont Die of Ignorance campaign, 1986.

I CANNOT REMEMBER with any clarity the first time that the Aids issue came onto my desk. I can remember much more exactly the time I became seriously frustrated about the way we in Margaret Thatchers government were handling the crisis. It was almost thirty years ago and I was Health and Social Security Secretary in her Cabinet. By the beginning of 1986, Aids cases were beginning to increase alarmingly. We were struggling to explain to the public the danger they faced and also to persuade other ministers that urgent measures were now needed. My view was that we needed a direct advertising campaign explaining how the virus was contracted and warning that there were no drugs or vaccinations that could be used to counter it. The prospect for those who ignored these warnings was death. It was that which justified (or so I thought) the government going into detail on sexual practices and drug taking information that was a million miles away from the usual advertising emanating from Whitehall. It was not a time to be too delicate. People needed to understand and to protect themselves, but this approach landed me in immediate and potentially fatal trouble. Standing in the way of such a blunt approach was the Iron Lady herself.