Mountains on the Market

Mountains on the Market

Industry, the Environment,

and the South

Randal L. Hall

Copyright 2012 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

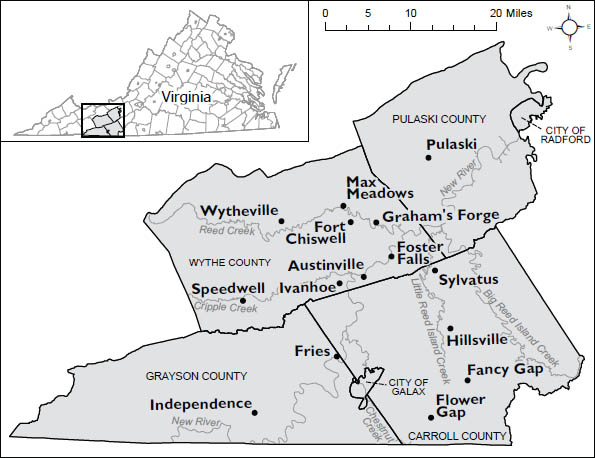

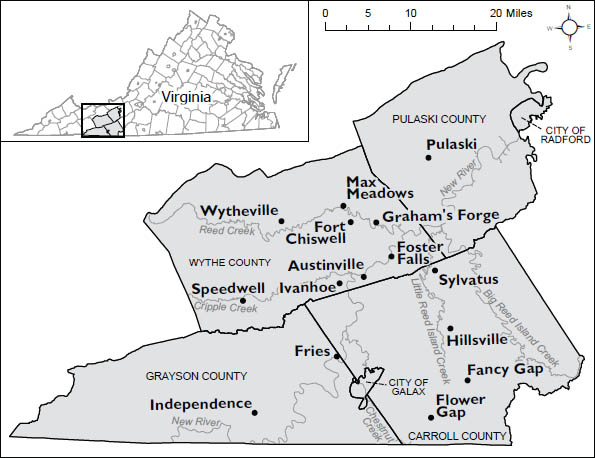

Frontispiece: Upper New River valley, Virginia

(GIS/Data Center, Fondren Library, Rice University)

16 15 14 13 12 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hall, Randal L., 1971

Mountains on the market : industry, the environment, and the South / Randal L. Hall. p. cm. (New directions in Southern history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-3624-0 (hbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8131-3649-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8131-4046-9 (epub)

1. IndustrializationNew River Valley (N.C.-W. Va.)History.

2. Natural resourcesNew River Valley (N.C.-W. Va.)History.

3. New River Valley (N.C.-W. Va.)Economic conditions.

4. New River Valley (N.C.-W. Va.)CommerceHistory. I. Title.

HC107.A127.H35 2012

330.97547dc23

2012008339

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of American University Presses

Member of the Association of American University Presses

To Jim Barefield, for commending to me verbs,

Henry Adams, and a sense of the ridiculous

Contents

Illustrations follow

Introduction

Here again, the very earth cries out beseechingly, for a way to market.S. F. C., A Ramble in Southwestern Virginia (1849)

Thomas Jefferson bears much responsibility for the longtime idealism about agrarian life in the United States, but he also revealed a deep faith in the power of industry and commerce. All the world is becoming commercial, he informed George Washington in March 1784. Our citizens have had too full a taste of the comforts furnished by the arts & manufactures to be debarred the use of them.

Representing Virginia in Congress, Jefferson was negotiating his home states cession of its western territories to the young United States. He had definite ideas about where Virginias western boundary should fallthe state should extend to the meridian of the mouth of the great Kanhaway River. He listed several reasons. First he put forth, That within that are our lead mines. Next he explained, This river rising in N. Carola traverses our whole latitude and offers to every part of it a channel for navigation & commerce to the Western Country. But the river would make deep demands on state resources: It is a channel which can not be opened but at immense expense and with every facility which an absolute power over both shores will give.

Jefferson had identified two issuesmineral resources and infrastructure needsthat preoccupied market-oriented residents of western Virginias mountains for the subsequent two centuries. The lead mines he mentioned abut the Blue Ridge Mountains along the New River, the name given the upper reaches of the Kanawha. The New River rises as two forks in Ashe County, North Carolina, along that states northern border. The branches combine and flow toward the northwest, eventually uniting with the Gauley River to form what we now know as the Kanawha. The New Rivers path through mineral-rich Virginia lands presented not only a great opportunity for commerce, but also a great challenge because of the areas isolation and the need to transport bulky minerals to more densely populated areas.

Industry grew slowly in early Virginia. The Northeast and then areas of the Midwest pushed the United States to the forefront of industrialized nations in the early nineteenth century, but the South lagged somewhat behind. The region developed industrial capacity ahead of most nations, but several factors explain the southern states poor showing relative to the parts of the United States that surged to world industrial leadership. Slave owners operating profitable plantations shaped much of the southern economy and regional politics; they benefited by buying manufactured items made elsewhere while keeping their focus on commercial crops. Their concentrated wealth and slaves lack of purchasing power stunted home markets, and the growing of lucrative staple crops dispersed the population because comparatively poor soils mandated large amounts of land for each plantation. The region thus did not have the large cities and broad consumer demand that catalyzed industry in the Northeast and Midwest. Canals and railroads often lost money because they had to meander far to reach nodes of customers. And the Appalachian Mountains ranked as the spot perhaps least hospitable to early industrialization owing to the inherent difficulty of transportation across the rugged terrain.

Despite these obstacles, entrepreneurs in the South developed a variety of industries. Railroads coursed through several parts of the region by the end of the 1850s, and the manufacturing of textiles and cotton gins as well as the mining and processing of iron and copper ore, coal, and phosphates commenced before the Civil War. And as Jefferson had expected, extractive industries took hold even along the New River in the Appalachian Mountains.

The lead mines lay in present-day Wythe County, Virginia. Wythe County (formed in 1790), Grayson County (taken from Wythe in 1793), and Carroll County (carved largely from Grayson in 1842) make up a substantial section of Virginias Blue Ridge Plateau and New River valley near the border with North Carolina. Lead was identified there in the 1750s, and miners worked the deposits by about 1761. In Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson also pointed out a second valuable mineral in this same highland spot: we are told of iron mines... on Chestnut creek, a branch By the 1780s, charcoal furnaces and forges were producing iron in the area, with a predominantly enslaved workforce, and over time iron challenged lead for precedence. In the 1850s, a third mineral garnered national attention: Carroll County played host to a boom in copper mining and smelting. Following the Civil War, zinc rose in importance as well, and industrial plants in neighboring Pulaski County (cut from Wythe and Montgomery counties in 1839) began to process both zinc and iron ore.

This book delves into the exploitation of natural resources along the upper New River over a 250-year period. Entrepreneurs and both local and northern corporations looked to extract and refine the valuable ores waiting beneath this predominantly agrarian landscape. Jeffersons remarks reveal that the state and federal governments, in particular the military, also tracked and pushed the development of mining there. As governor of Virginia in 1780, Jefferson himself dispatched troops to guard the lead mines against a rumored Loyalist uprising during the Revolutionary War, and military needs likewise dictated the mines fate during the Civil War. Government geologists continued to map and observe the area into the Cold War era. Natural resources became national resources. Entrepreneurs often drew on the state and national governments expertisefor instance, by relying on the findings of the antebellum state geological survey and, following the Civil War, by using the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to improve commercial navigation on the river. Other geologists acted as paid, private consultants to mining firms. Advocates of industrialization, hoping to boost the regions economy and image after the Civil War, had much to say about the areas prospects. Networks of geologists passed along scientific data, and families and clusters of local investors refined and bequeathed knowledge of the mining business. The expansion of railroads brought the area further into the industrial mainstream. As the nineteenth century neared its end, the New River flowed past enterprises ever more thoroughly incorporated into the national economic web.

Next page

Member of the Association of American University Presses

Member of the Association of American University Presses