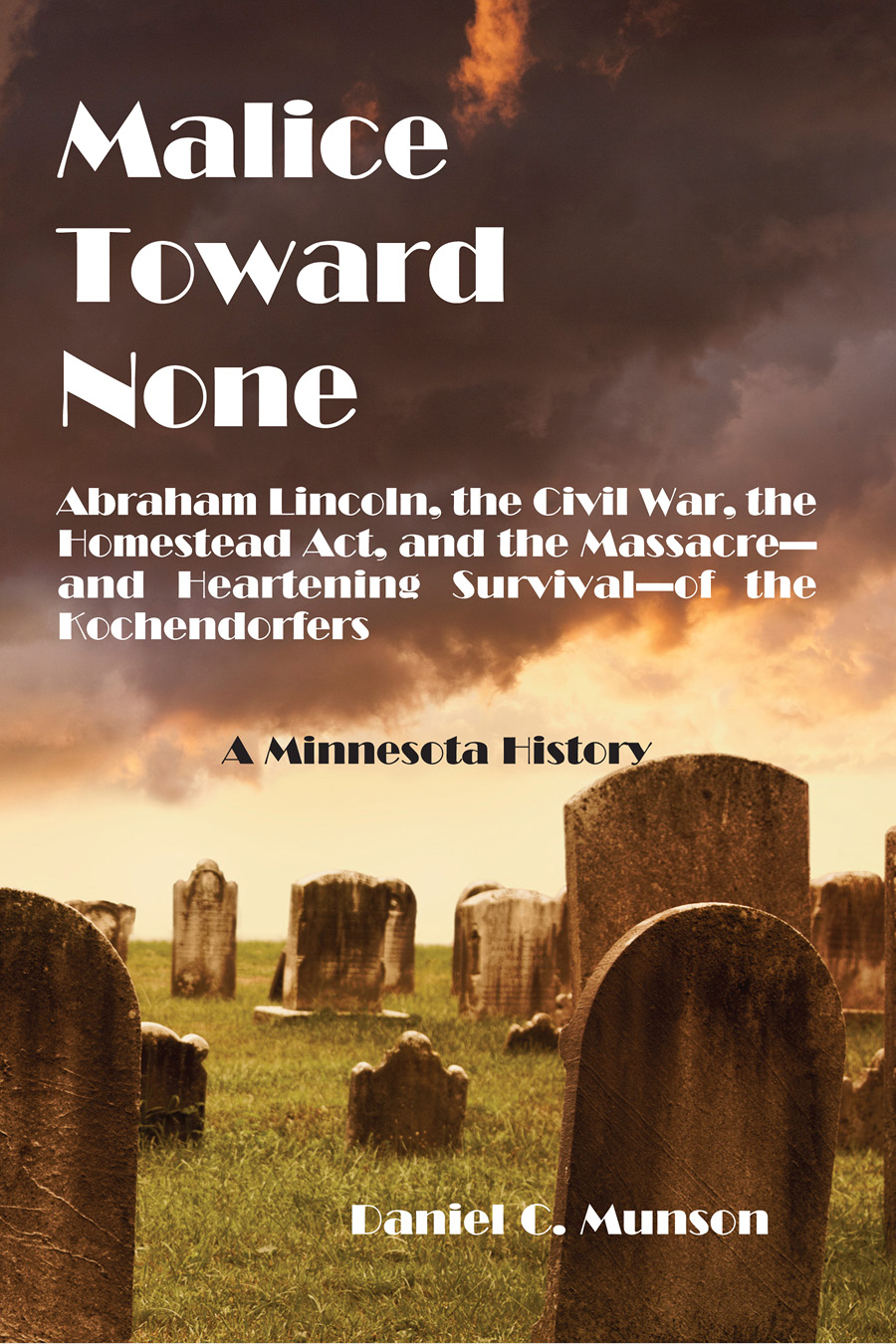

MALICE TOWARD NONE

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, THE CIVIL WAR, THE HOMESTEAD ACT, AND THE MASSACREAND HEARTENING SURVIVALOF THE

KOCHENDORFERS

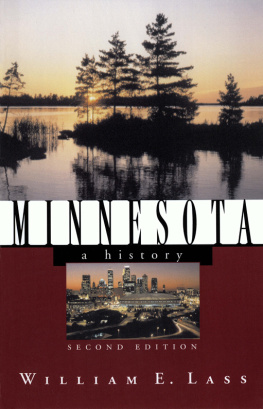

A Minnesota History

Daniel C. Munson

North Star Press of St. Cloud, Inc.

St. Cloud, Minnesota

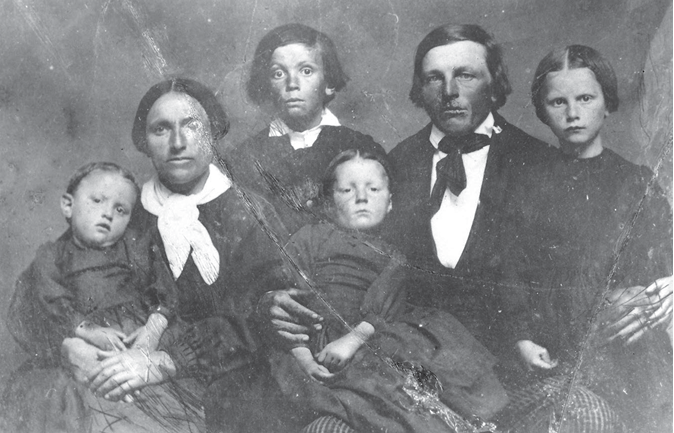

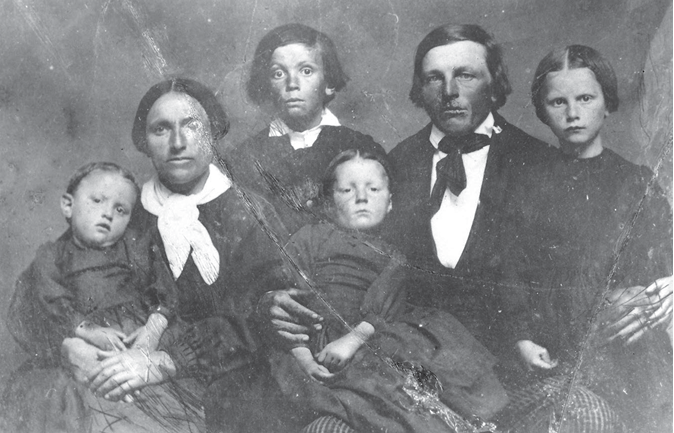

The Kochendorfer Family in 1858-1859. Left to right: Margaret, Catherine, Johan, Jr., daughter Catherine, Johan, Sr., and Rosina. (From the collection of the Brown County Historical Society, New Ulm, Minnesota.

Copyright 2014 Daniel C. Munson

ISBN: 978-0-8783 - 716-7

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

Published by

North Star Press of St. Cloud, Inc.

P.O. Box 451

St. Cloud, MN 56302

northstarpress.com

Dedication

To Marilyn and Judy and Joe and Eileen and Nancy:

Thank you for taking the time to share with me your marvelous family photos and stories.

Table of Contents

Prologue

I come from a practical Minnesota family, and our family traditions often accomplish a number of goals at once. Were patriotic, and we observe national holidays, but not with any grand gestures. We like to exercise, but would never dream of organizing a family event around something that can be done easily enough on ones own time. So the discovery that visiting many of the family forebears gravesites in an old cemetery near the state capital in St. Paul could be combined with a leisurely bike ride along a bike trail that passes very near my suburban house now makes for a sort of Memorial Day Weekend tradition.

Memorial Day in Minnesota is often blessed with beauty both botanic and climatic. The grass is lush and green, and often there are felt the first hints of summer warmth. The flowering fruit trees, plum and cherry and crabapple, are a little past their prime but often still brilliant. The bridal veil bushes are in full bloom, and the hydrangea that face south are already beginning to show blossoms.

There are often three generations of us on our bicycles, and we head for Oakland Cemetery, just up a short, steep hill past the trail head. Our plan is to visit and clean off a few of the stones bearing the family names, but the weather is often too nice to hurry away. The oak trees form an excellent canopythe name of the cemetery is no misnomerand we sometimes sit on a small hill near the cemetery chapel and sip drinks and marvel at the beauty that is springtime and the effects of over a century of patient grounds keeping.

Ive hunted up a few other notable headstones at this same cemetery, the oldest cemetery in our somewhat young state, and I like to point them out and tell the stories of the semi-famous people buried there to my fellow bikers. There are the old state governors, the wealthy businessmen. The Civil War veterans have their own distinctive headstones and a reserved area.

Our family has a few descendants buried there of whom we can be proud. My paternal grandmothers grandfather was one of the states first Methodist ministers, having arrived in St. Paul around 1860. He and his immediate family are buried along the side of a small hill that overlooks the east entrance.

I like to read the prominent headstones. The names occasionally give you a chuckle, and youre reminded of how first names are somewhat faddish: Lucius, Mathildethese are not the names being written on todays birth certificates.

Our family forebears are mostly Germanindeed, my mother biking alongside me is a German immigrantand we enjoy some of the German family names. One year, I noticed one on a gravestone only a few dozen yards from where great-great Grandpa, Reverend Rotert, is buried: Kochendorfer. Thats a good one! I look more closely. There are three names: thirty-eight-year-old Johan, thirty-six-year-old Catherine, and three-year-old Sarah. The inscription is sad: Victims of Redwood Falls Massacre Aug. 1862.

Here is a teachable moment! I turn to the others nearby and point to the inscription, and ask if any of my young charges can explain who or what these poor souls were victims of? One of my nieces, a shy fourteen-year-old at the time and nobodys fool, says in a soft voice: the Indians. Thats right, I tell them. Minnesota schoolchildren are often taught about the Indian Uprising of 1862 that took the lives of hundreds of the states residents, but it takes a quick young mind to make the connection between the date and the place. Im a bit of a history buff, but I didnt know exactly where those awful events occurred. Redwood Falls is south and west of us, along the Minnesota River, a good hundred miles away.

There were other things to concentrate on that morning. We had to agree on how much longer to stay at Oakland, because the four mile trek back home with a half-dozen young schoolchildren required a little organization. We also had to discuss which restaurant we would all go to for lunch. It was only later that the questions began to surface: What were those bodies doing there?

Nobody would have taken three dead bodies one hundred miles in 1862 just to bury them at Oakland Cemetery. How did those three unfortunate Kochendorfers get here to St. Paul? An interesting question, I thought. I wondered if there might be a good story behind it all. This book is the work of puzzling out the answer to this seemingly simple question.

The Kochendorfer Gravestone. (Courtesy of Curt Dahlin)

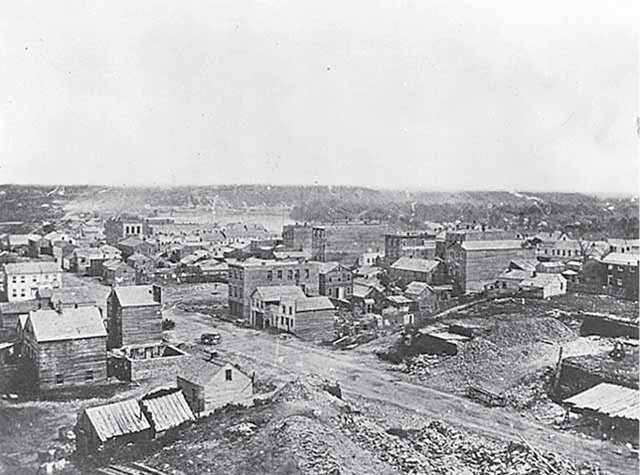

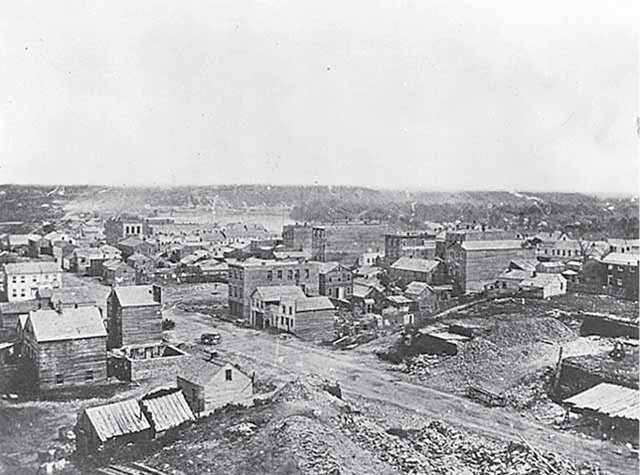

St. Paul, 1857.

The Antebellum North

I

R ussian Czar Alexander I created a problem for himself when his soldiers drove the nomadic Tartars out of Bessarabiathe area north and east of Romania and north of the Black Seain the early years of the nineteenth century. The Tartars hadnt been doing much with the Bessarabian soil, but now even they were gone. Russian land management being what it was, the czar had to formulate a plan. His landowning class wasnt all that interested in farming itthey had plenty of land where they wereand his serfs were incapable of organizing the effort required.

His solution was simple, and informed by the realities of European life at the time. The czar offered Bessarabian land to Germans willing to own and work it. He made them an enticing offer: zero-interest loans, religious freedom, exemption from military service, and a ten year reprieve from Russian taxesand the Germans came. A half-century before, Catherine the Great had offered land, religious freedom, and exemptions from military service to German-speaking AnabaptistsMennoniteswho proved good farmers, so the Russian aristocracy was comfortable with the idea of German farmers cultivating Russian soil. The Czar knew that Germany had many young people willing to apply the latest farming methods. These Germans had everything requiredexcept farmland. The farmland in their native Germany was expensive and seldom up for sale.

Next page