Contents

Guide

Page List

They left their Southern Lands,

They sailed across the sea;

They fought the Hun, they fought the Turk

For truth and liberty.

Now Anzac Day has come to stay,

And bring us sacred joy;

Though wooden crosses be swept away

Well never forget our boys.

Jane Morison, Well never forget our boys, 1917

Be it Tipperary or E Pari Ra, the morning reveille or the bugles last post, concert parties at the front or patriotic songs at home, music was central to New Zealands experience of the First World War. In Good-Bye Maoriland, the acclaimed author of Blue Smoke: The Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music 19181964 introduces us to the songs and sounds of the war in order to take us deep inside the human experience.

Chris Bourkes Good-bye Maoriland is an impeccably researched account of the influence of music in World War I from military bands and concert parties to Maori music and patriotic song writing. Profusely illustrated and highly readable, it will attract anyone interested in war and the cultural history of New Zealand.

Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) Christopher Pugsley, ONZM, DPhil, FRHistS

Chris Bourke is a writer, journalist, editor and radio producer. He has been arts and books editor at the NZ Listener, editor of Rip It Up and producer of Radio New Zealands Saturday Morning hosted by Kim Hill and John Campbell. He wrote the best-selling, definitive biography of Crowded House, Something So Strong (Pan Macmillan, 1997), and Blue Smoke: The Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music, 19181964 (Auckland University Press, 2010). At the 2011 New Zealand Post Book Awards Blue Smoke won the Peoples Choice Award, the General Nonfiction Award and the Book of the Year Award. Chris Bourke is currently content director at Audioculture: The Noisy Library of New Zealand Music (www.audioculture.co.nz).

For Tom McWilliams

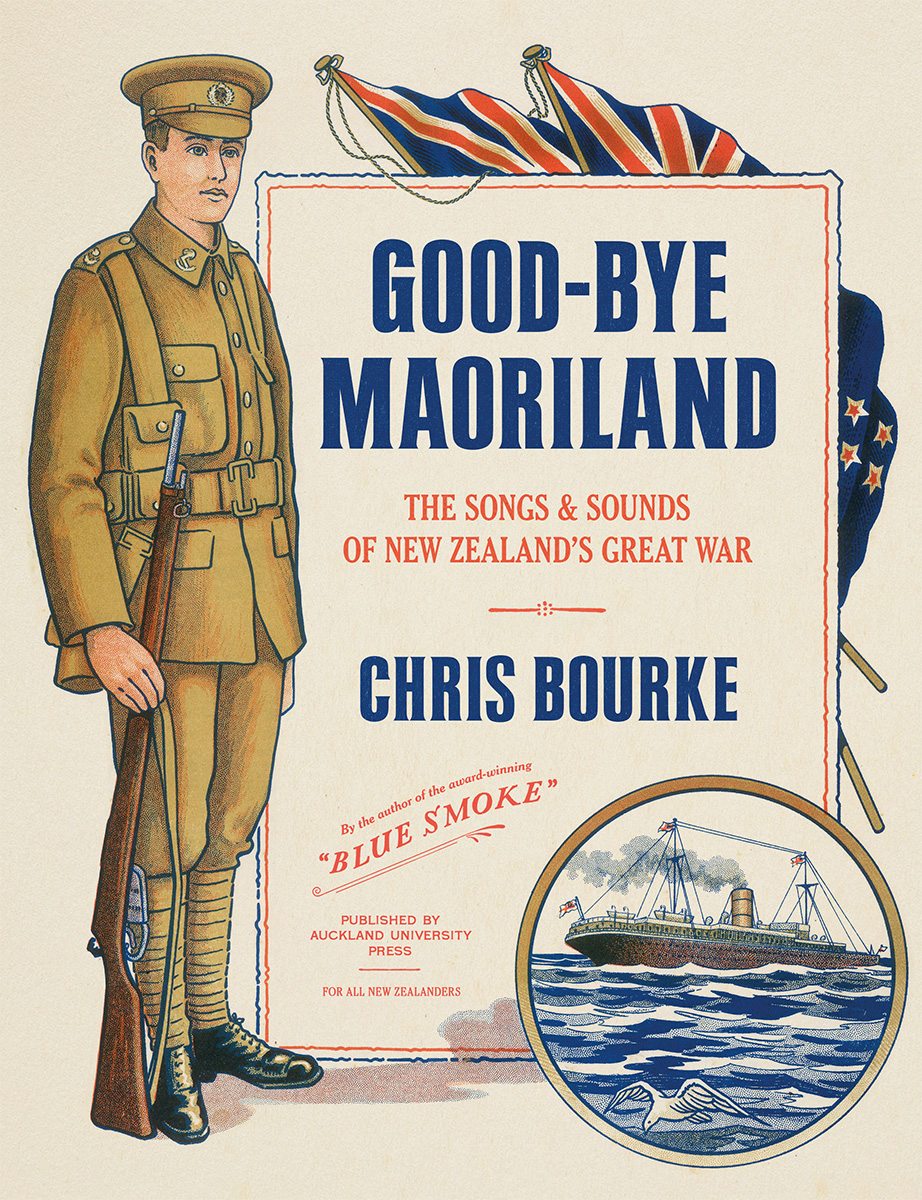

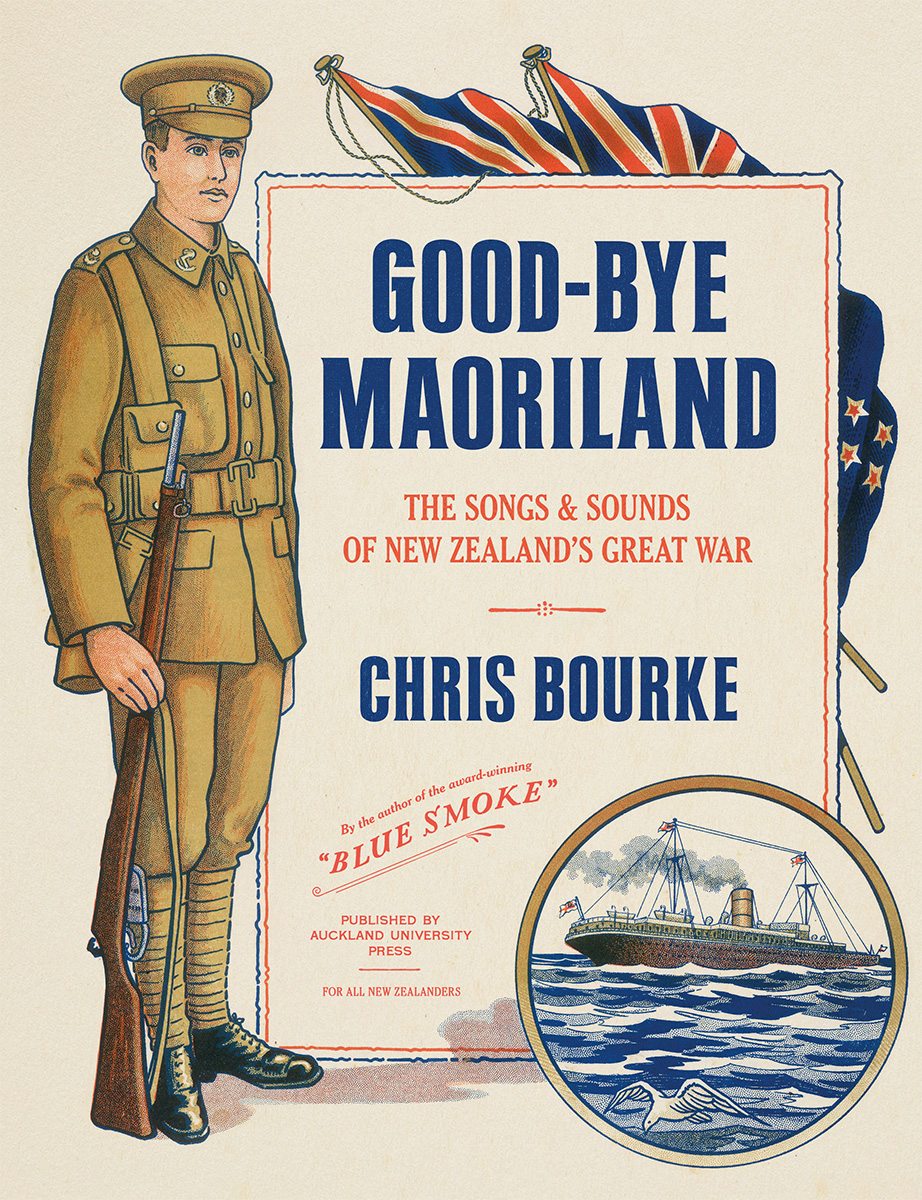

GOOD-BYE MAORILAND

THE SONGS & SOUNDS OF NEW ZEALANDS GREAT WAR

CHRIS BOURKE

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

SAY AU REVOIR AND NOT GOOD-BYE

CHAPTER TWO

BANDS OF BROTHERS

CHAPTER THREE

MUSIC IN KHAKI

CHAPTER FOUR

HELP THE LADS WHO WILL FIGHT YOUR FIGHT

CHAPTER FIVE

WE SHALL GET THERE IN TIME

CHAPTER SIX

WAIATA MAORI

CHAPTER SEVEN

KIWIS, TUIS AND PIERROTS

CHAPTER EIGHT

DAWN CHORUS

A souvenir handkerchief from the First World War brought back to New Zealand by Private Edwin Battensby of the Auckland Infantry Battalion, a former bushman wounded at Gallipoli. In the centre is the music of Its a Long, Long Way to Tipperary above an image of marching soldiers. A corner edge is stamped Oamaru, N.Z..

THE KAURI MUSEUM, MATAKOHE

PREFACE

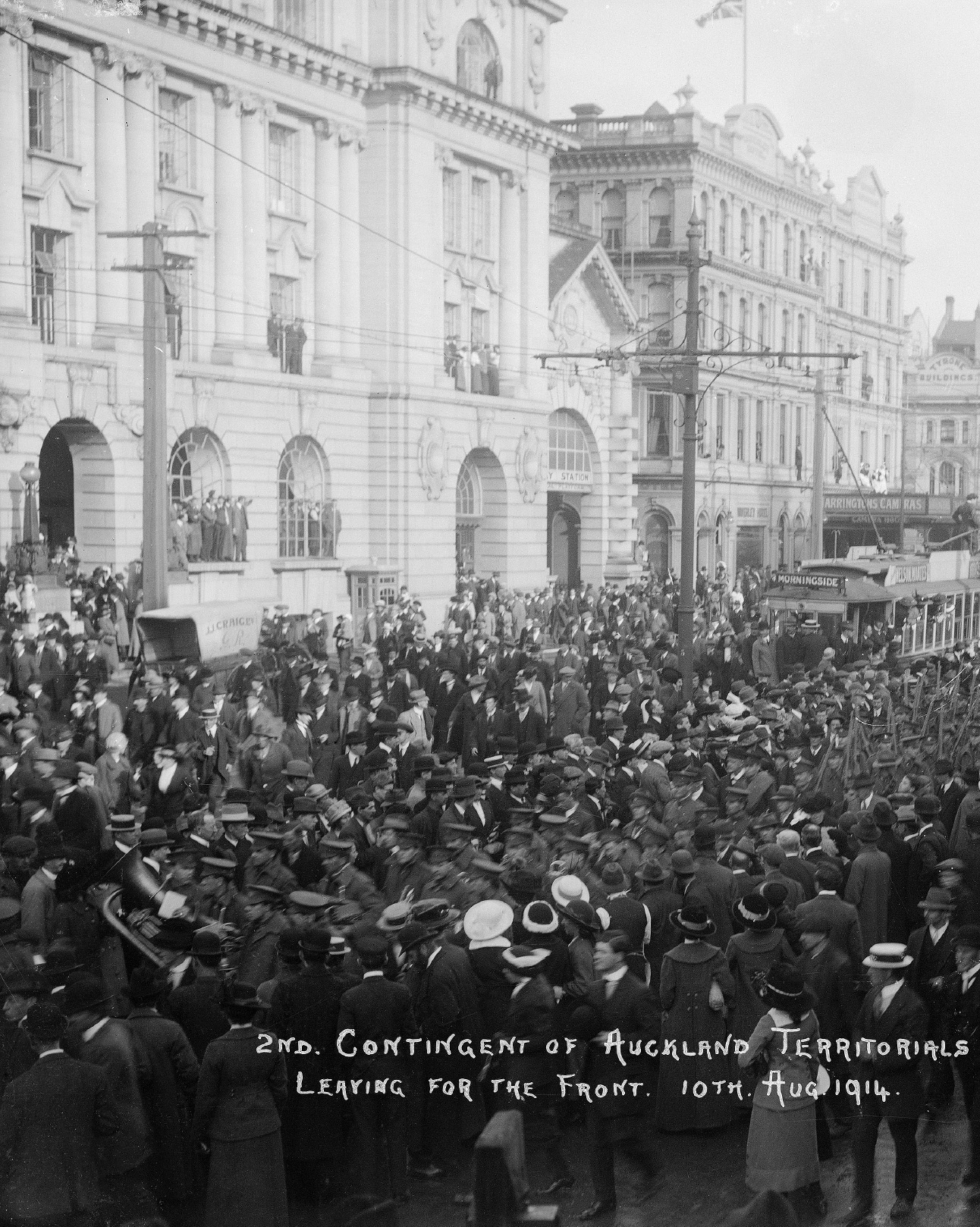

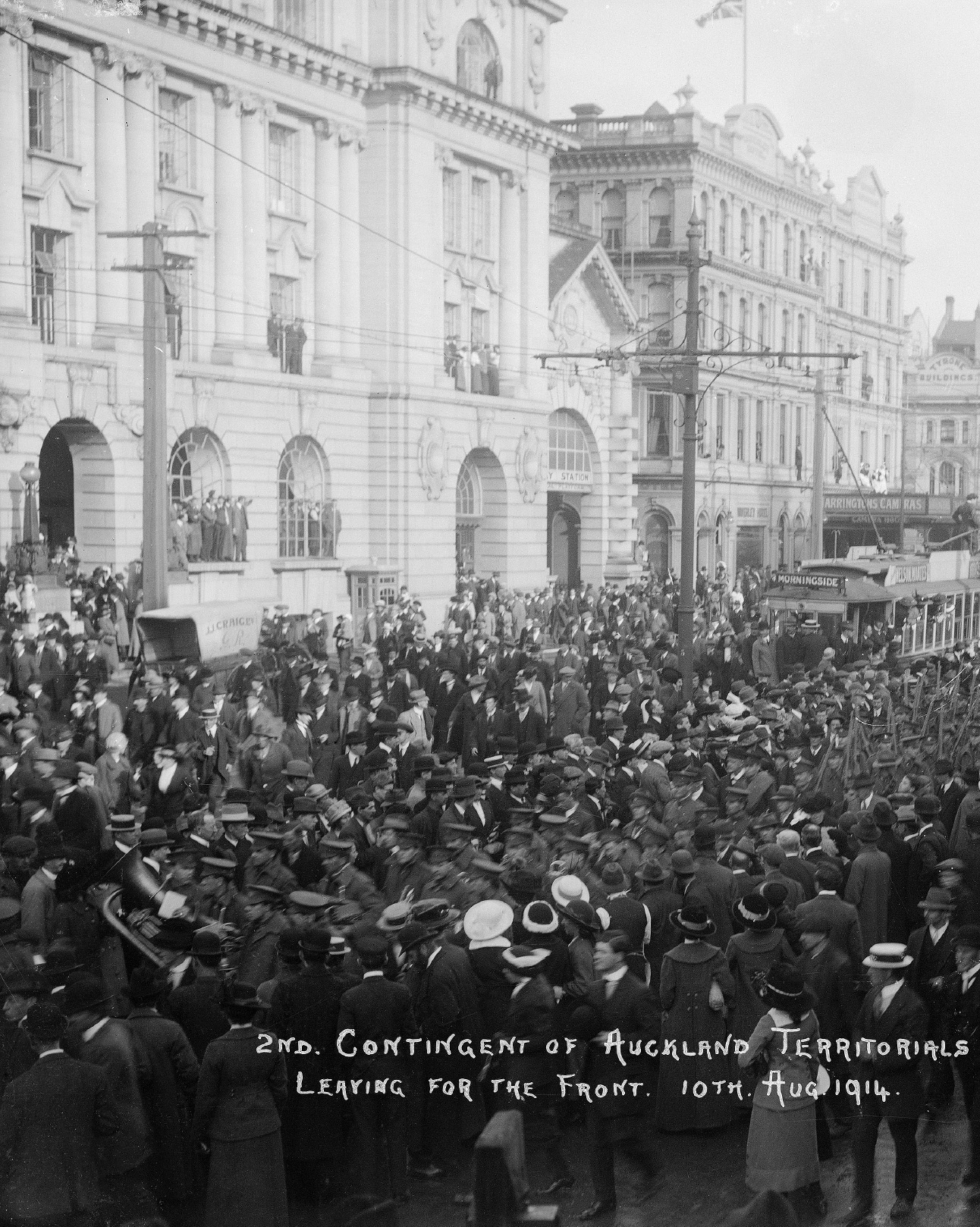

Good-bye Maoriland began on Lambton Quay, Wellington, just south of the Cenotaph. As well as the symbols of two world wars, that stretch of pavement also carries with it the ghosts of many NZEF reinforcements who marched past, led by brass bands, including a Maori contingent in 1915 whose men clutched freshly printed cards featuring the lyrics of Tipirere.

In 2010, shortly after the publication of Blue Smoke, my book about mid-twentieth century New Zealand popular music, I ran into Vincent OSullivan near Parsons legendary bookshop, now gone. I know what you should do next, he instantly said. A history of New Zealand music during the First World War. All the historians are working on the war, but none will cover the music. At the time, Vincent was writing a libretto for Ross Harriss opera Brass Poppies, which describes how a small group of New Zealanders experienced Gallipoli in 1915, at home and on Chunuk Bair. The lead character is Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone, now celebrated for his courage at Gallipoli. In this book he has a walk-on role as an officer whose disdainful attitude towards military musicians changed once he saw that they, too, were capable of great courage.

Good-bye Maoriland examines the role music played in New Zealands response to the war at home and at the front. It describes how music was used in wartime society: the settings in which it was heard, the repertoire performed, the characters who provided it to the community. One chapter discusses some of the approximately 200 original songs written in response to the war and how they evolved as it continued. At first, many were bellicose and imperialistic, although some were poignant; by the end, they mourned the men who were left behind. Good-bye Maoriland is the title of one, by a prolific songwriter using the pseudonym Raymond Hope. When it was published in November 1914, reviewers praised its exuberance; it was the kind of song, wrote the Southland Times, that makes the rafters rattle when half a dozen full-lunged vocalists sing it. The words seem to be in entire accord with the spirit of the song and throughout there is the bold, defined beat of the march.

It was a recruiting song, written to inspire men to follow the Empires call to Europe. There is an unintended pathos to its title, which says farewell to a romanticised new world while its singer ventures to sort out the old. If New Zealand was ever a Utopia in the South Seas, that idyll is about to be lost. While many of the 200 songs refer to New Zealand helping Home in its time of crisis, others use Maoriland imagery: not everyone thought New Zealand was just Britains most distant province. Now, the term Maoriland seems almost as patronising as the imperial military authorities in Britain were towards Maori soldiers. Then, it was typically used without guile; it may have described the exotic or the other, and involved appropriation, but it also suggested positive possibilities. The war instantly rendered the term obsolete.

In Maoriland: New Zealand Literature 18721914, literary historians Jane Stafford and Mark Williams paid tribute to the writers of the colonial, pre-war era without pretending there were any lost masterpieces. The same can be said of New Zealands wartime songwriters: there is no unheralded Schubert or Berlin. (Although I do find the careful, four-part harmony of Jane Morisons Well Never Forget Our Boys deeply moving.) But their songs, and the imagery of their lyrics and graphics, express contemporary attitudes. Even the corn be it kowhai gold or bulldog bluster tells us how civilian New Zealand reacted to the war.

While never threatening Its a Long, Long Way to Tipperary, these locally written songs were widely performed, in public and private settings. Now, what saves them from disappearing is the dedicated work of collectors such as sheet-music archaeologist and proselytiser David Dell. Ironically, considering the condescension towards Maori who enlisted and the ruthlessness towards those who didnt it is the Maori songs from the period that are still heard today.