Contents

Guide

Page List

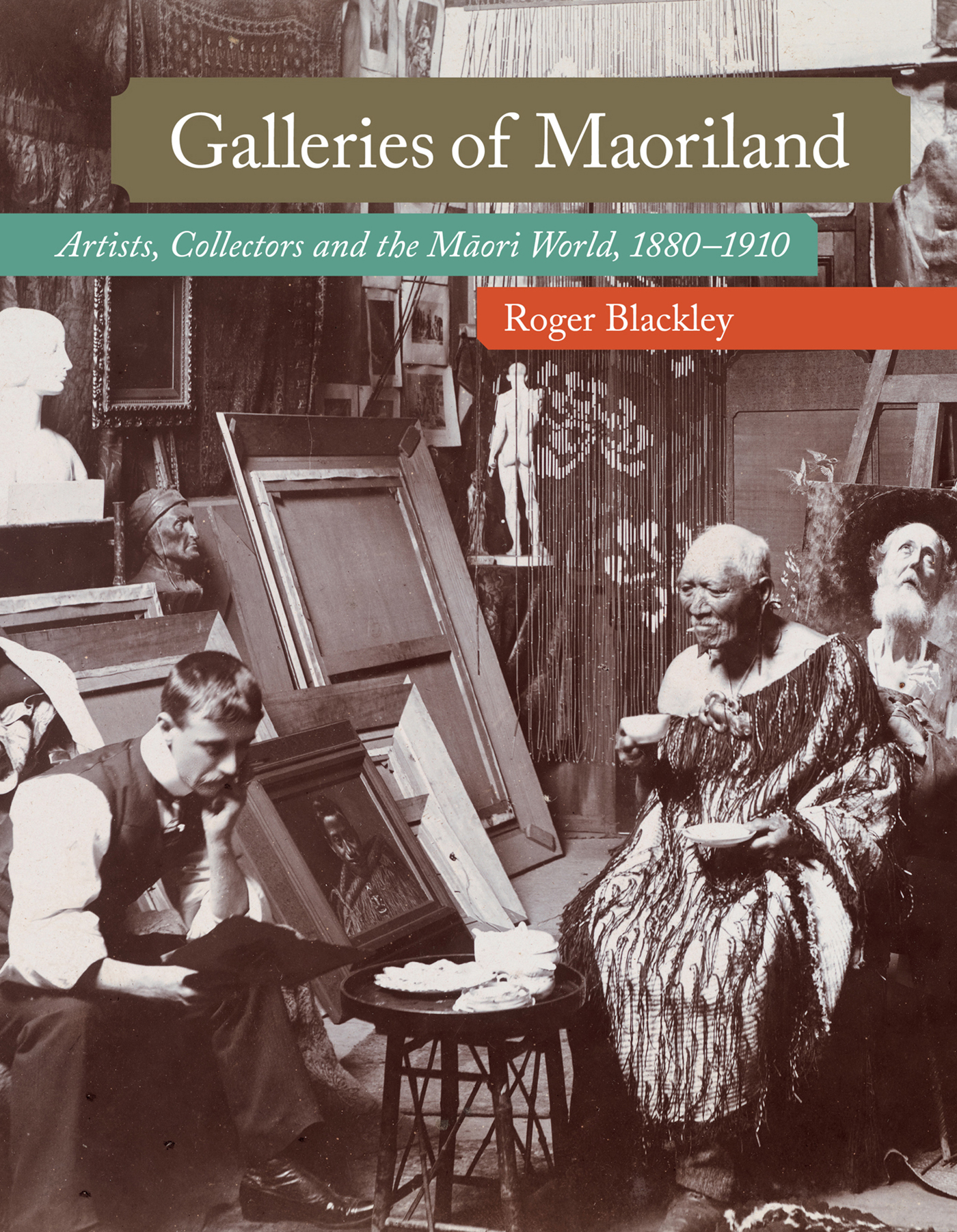

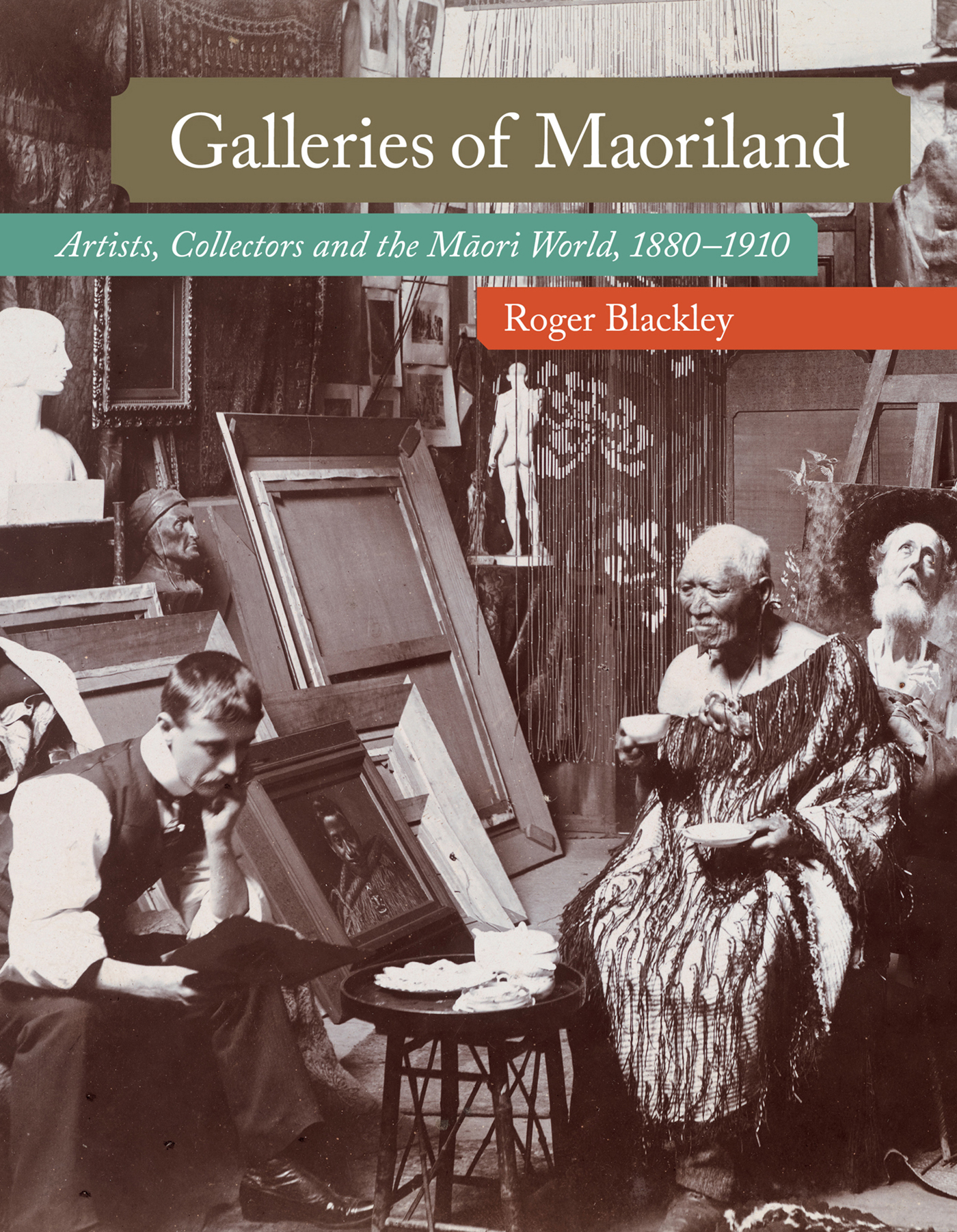

Galleries of Maoriland introduces us to the many ways in which Pkeh discovered, created, propagated and romanticised the Mori world at the turn of the century in the paintings of Lindauer and Goldie; among artists, patrons, collectors and audiences; inside the Polynesian Society and the Dominion Museum; and among stolen artefacts and fantastical accounts of the Mori past.

The culture of Maoriland was a Pkeh creation. But Galleries of Maoriland shows that Mori were not merely passive victims: they too had a stake in this process of romanticisation. What, this book asks, were some of the Mori purposes that were served by curio displays, portrait collections, and the wider ethnological culture? Why did the idealisation of an ancient Mori world, which obsessed ethnological inquirers and artists alike, appeal also to Mori? Who precisely were the Mori participants in this culture, and what were their motives?

Galleries of Maoriland looks at Mori prehistory in Pkeh art; the enthusiasm of Pkeh and Mori for portraiture and recreations of ancient life; the trade in Mori curios; and the international exhibition of this colonial culture. By illuminating New Zealands artistic and ethnographic economy at the turn of the twentieth century, this book provides a new understanding of our art and our culture.

Roger Blackley is an associate professor in art history at Victoria University of Wellington. From 1983 to 1998 he was the curator of historical New Zealand art at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tmaki. He is the author of a number of books, including the bestselling Goldie (Auckland Art Gallery/David Bateman, 1997).

Steffano Francis Webb, Doorway at the Tourist Department Court at the Christchurch Exhibition, 19067, scan from dry-plate glass negative. Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/1-5023-G.

Galleries of Maoriland

Artists, Collectors and the Mori World, 18801910

Roger Blackley

Published as part of the

Gerrard & Marti Friedlander

Creative Lives Series.

Contents

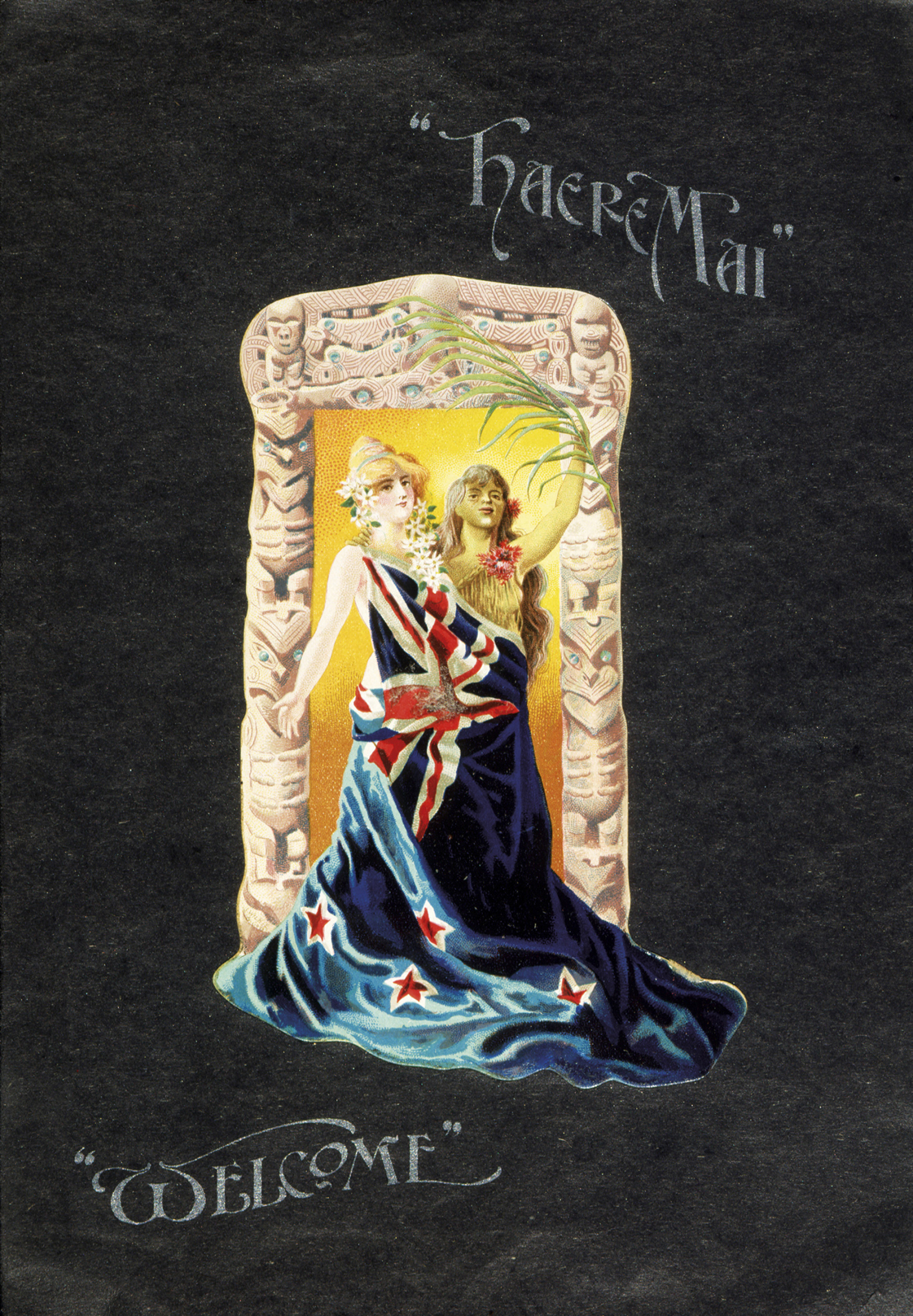

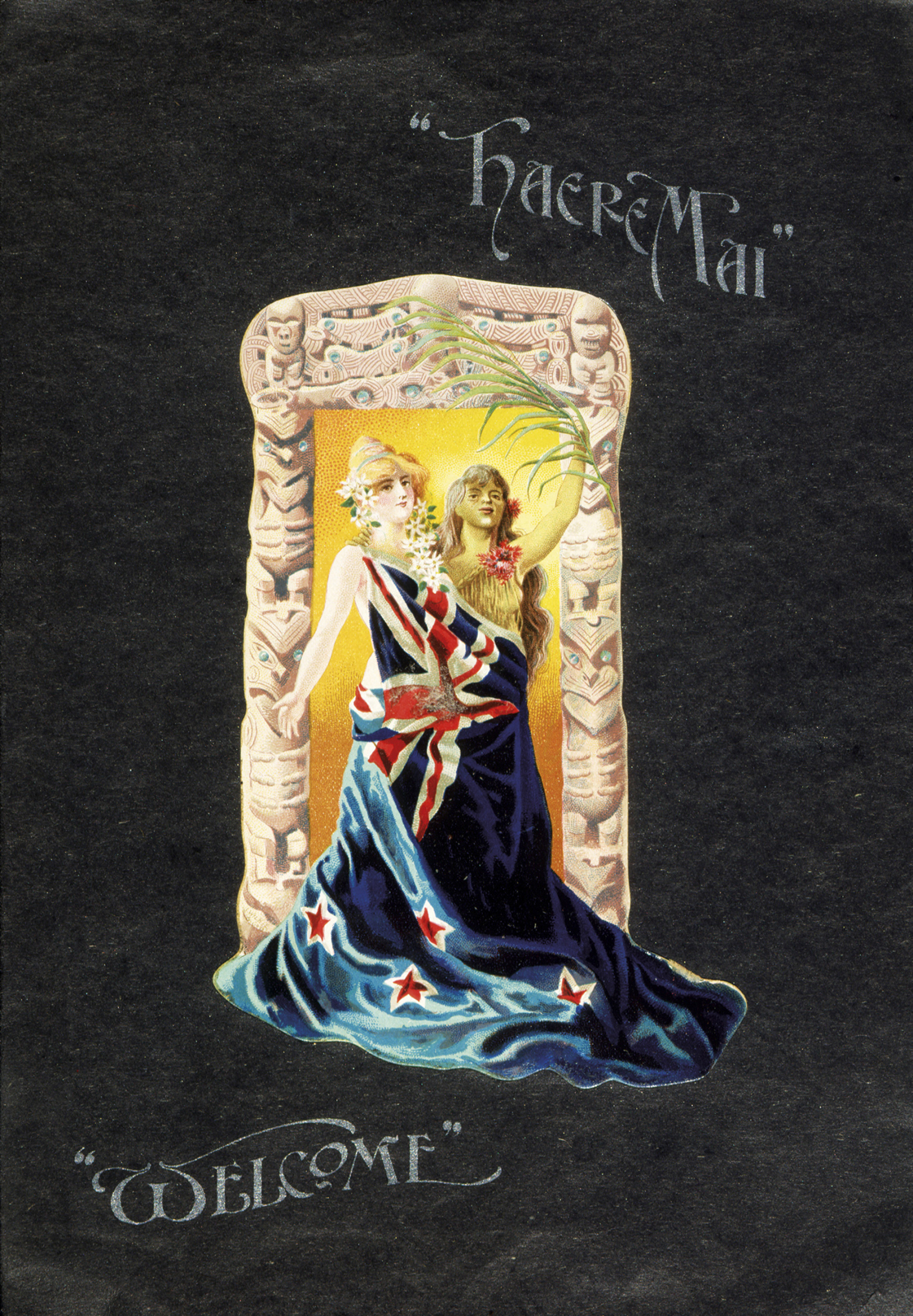

Haere Mai, Welcome, invitation booklet cover, New Zealand International Exhibition, 1906, chromolithograph, 155 110 mm, laid on cover, 256 178 mm. ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, EPH-B-EXHIBITION-1906-02-COVER

Preface

D O WE CHOOSE OUR FIELDS OF RESEARCH, or do they choose us? I retain vivid memories of childhood visits to Wellington some fifty years ago, especially the experience of the Dominion Museum. My favourite area was the vast Maori Hall, where dimly lit glass cabinets held artefacts shown in front of mysterious pictures that depicted people and places of the lost world from which the objects had come images I now know were hand-coloured lithographs after watercolours by George French Angas. I remember a bronze-coloured bust standing sentinel near the entrance, which a label simply identified as Wharekauri by Nelson Illingworth. Keen-eyed scrutiny of several white patches suggested that the portrait effigy was made of plaster rather than bronze, but now I know that Wharekauri belongs to a group of miraculously preserved ethnographic busts that were specially commissioned by the museum. Also on display near the entrance were two preserved Mori heads, artefacts that were more perplexing than anything else in the entire museum. I still remember the question that furrowed my young brow could these be real human heads?

Two decades on, during my early days as a curator at the Auckland Art Gallery, colleagues encouraged me to display examples of what we had recently learned to call taonga (Mori treasures) within the gallery of Mori portraits. This would mean that the public could see woven garments and polished greenstones in the flesh, so to speak. Knowing that the gallery retained ownership of Sir George Greys Mori collection housed at the Auckland Museum, I duly selected some attractive pieces, negotiated the loans, wrote informative labels including a biographical text on Grey, installed everything in two elegant cases, and thought it all looked rather splendid. Before long, however, I was exposed to the contempt of Mori visitors who had come to the gallery in order to revere the portraits but who encountered the taonga with palpable disdain. Inevitably, one person would read out the label text that linked Grey with the Waikato war, whereupon the entire group would vent their anger over the exhibition of what had instantly been transformed into war booty.

This episode provided a significant initiation into the knowledge that objects can acquire radically different meanings when they cross cultural boundaries. The mind-blowing realisation was that for many Mori visitors the genuine taonga in the room were the ancestral portraits by the immigrant painter Gottfried Lindauer, rather than the authentic Mori treasures that were delighting other visitors, including some Mori but more particularly the tourist other for whom the artefact display was in part intended. Even my curatorial right to display such material was contested by a Mori academic whose greatest annoyance was my description of the mere pounamu as clubs, when as thrusting weapons they should have been glossed as cleavers. The experience did not stop me from including relevant Mori objects within subsequent exhibitions of portraits, but it did provoke intense reflection regarding the complex relationships between Mori objects and Mori images, as well as the protocols and responsibilities surrounding their exhibition and reproduction.

The experience of curating the travelling exhibition Goldie (199799), the first retrospective of New Zealands old master of Mori portraiture, exposed me to the reality of a bicultural reception of his work that had hitherto evaded the art-historical radar.

The more I investigated, the more convinced I became that Mori objects shared an affinity with Mori portraits, and vice versa. This is the message currently communicated by the spectacular line-up of Goldie portraits on show within He Taonga Mori, the Mori Court at the Auckland Museum. The paintings, which were donated by Goldies widow in 1951 when the artists reputation was at its nadir, offer a magnificent foil to the surrounding taonga. At Te Papa, portraits have regularly appeared within Mori-curated exhibitions including Kahu Ora: Living Cloaks, a spectacular 2012 show of historic Mori cloaks that incorporated many portrait photographs, as well as paintings by Lindauer and Goldie that clearly served a wider purpose than mere illustration of the garments worn by the portrait subjects. In the face of Mori respect for painted portraits including Goldies melancholy imagery Pkeh intellectuals encounter difficulty in following the modernist imperative of denouncing such works as tendentious colonial documents intended to memorialise a dying race. An alternative strategy, deployed by Te Papas curators at the time of its opening in 1998, involved castigation of the academic tribe personified by an artist such as Goldie, and the recasting of this category of artist as a dying race.