ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There is a saying, M te huruhuru te manu ka rere, or, It is the feathers that enable the bird to fly. In this case, the feathers, or funds, enabling the research to take place were provided by the Royal Society of New Zealands Marsden Fund. Financial support during the final writing stage of the work was subsequently provided by Copyright Licensing Limited. To both institutions I am extremely grateful.

I am also grateful to many individuals who have generously contributed in a wide variety of ways. My family, especially my husband Tony and father-in-law Ian Petrie, have offered consistent personal support. And special thanks go to Mrs Hohipere Tarau, who not only translated a great deal of Mori-language material but was also a very empathetic sounding board for my ideas in the early years of the project. So, too, were the staff of the Mori Studies Department at the University of Auckland. Philip Abela and the staff of the Auckland University Library, as well as those at the Alexander Turnbull, Auckland City, and Hocken libraries have been sources of information and great courtesy over the projects several years of incubation. Patu Hohepa, Hone Sadler, Jane McRae, Chris Tremewan, Patricia Te Arapo Wallace, Maureen Lander, Tanengapuia Te Rangiawhina Mokena, Angela Wanhalla, Anne Salmond, Sally Nicholas, Vavao Fetui, Ross Clark, Michael Belgrave, Hirini Kaa, Angela Middleton, and Ian Smith are just a few of the many individuals who have been kind enough to give of their time and expertise as and when I sought it. I have also benefited from the comments and suggestions of two anonymous referees. Finally, I am very grateful for the expertise and boundless patience of editor Mike Wagg, proofreader Ginny Sullivan, and the staff of Auckland University Press. But, in the end and despite all their help and advice, the responsibility for errors or omissions remains mine alone.

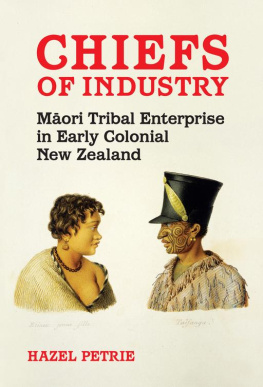

INTRODUCTION

J AKE THE MUSS (OR MUSCLES) HEKE, LEAD CHARACTER IN THE novel and movie Once Were Warriors, has acquired almost iconic status in popular New Zealand culture. He represents the stereotypical hard-drinking, wife-beating, irresponsible, disenfranchised Mori male of modern times. Apparently by way of justifying his bad behaviour, Jake tells his family that his violent nature is a consequence of his slave ancestry and the familys 500 years of humiliation. Mori used to fight each other, he explains, and, because his line was defeated, they were taken as slaves. For his wife Beth, that revelation conjures up images linking Mori slavery with that suffered by Africans in America, so she tells their children:

Us Maoris used to practise slavery just like them poor Negroes had to endure in America . Yet to read the newspapers, on the TV every damn day, youd think were descended from a packa angels, and its the Pakeha [New Zealander of European descent] whos the devil. Clicking her tongue: Just shows, were all good, and were all bad.

Despite the wide variety of forms of slavery or bondage throughout world history, familiarity with African-American history, acquired through books, films, and television documentaries, has led many Westerners, including New Zealanders, to comprehend slavery in a particular way as black people, bought and sold, labouring on plantations, But because the history of Mori slavery and the place of war captives in Mori society has been largely unexplored thus far, popular assumptions relating to Mori so-called slavery, its function, and British impacts on it have not been subject to scrutiny and may have been too readily accepted.

The trans-Atlantic trade in Africans and debate over the possibility of abolishing it were at the forefront of Western, especially British, minds as the colonisation of New Zealand was being contemplated. Consequently, that system became the key point of reference for understanding the place of those people already referred to as slaves by missionaries and others who reported on New Zealand affairs. That loose labelling of war captives in Mori society as slaves has had the effect of conflating two, quite different, institutions and led to these captives being perceived in much the same way as African slaves in the Americas rather than as the prisoners taken in intertribal warfare that they almost always were.

Misapprehensions began early. Even contemporary observers could not agree on the general tenor of what was referred to as Mori slavery. Some said it was benign but others referred to cruelty, the degraded status of slaves, and the tenuousness of their hold on life. In later times, the victory achieved by Christianity and English law in securing their freedom through the introduction of new moral and legal codes appears to have been an assumption made without supporting evidence.

Nevertheless, it is the shock-horror descriptions of the slave experience recorded by some outsiders that continue to resonate especially loudly today.been stressed, oral traditions tell of slaves as faithful companions, who risked life and limb to save their masters and mistresses or facilitate the path of true love. Such stories contain their own biases, of course, but nineteenth-century accounts confirm the great variety of experience. There is also evidence that those who abused war captives could be subjected to severe censure or even banishment from their community, implying that such behaviour, without just cause, breached accepted codes. As will be seen, captives elicited different responses and lived in varying degrees of comfort or discomfort. Cruel, inhuman treatment was not a universal standard.

Even when free to go home, some captives chose to stay where they had settled. Their individual responses almost certainly related to their personal situations. Remarkable differences in their lives after capture related to a number of variables, including the circumstances of their acquisition, their pre-captive rank, and their capacity to improve their position through their abilities or attitudes.

Glimpses of what life was really like for war captives in Mori society appear in a variety of sources and provide a foundation for considering whether slavery is an appropriate term for each situation and whether it should be universally applied. Slavery is an all-purpose word, rarely to be trusted. So the key to much misunderstanding appears to lie in how it is defined and how systems of slavery are perceived. Possibly the most misused word in the English language, slavery has become a metaphor for extreme inequality, for subordination, deprivation and discrimination.

Despite the multitude of applications of the word slavery, it has all too often been assumed that those many institutions (if that is what they were historically) can be discussed and theorised cross-culturally.

Given that slavery, being a nebulous concept, is a difficult word to define, it should not be surprising that translations of Mori text have served to confuse the historical record even further. Political and ideological impulses may also be responsible for distortion in translation, but cultural differences go some way towards explaining why English words such as slave and slavery have been applied to a variety of situations and circumstances that are not necessarily analogous to English meanings. When a word from one language is translated into another, its original connotation may not be conveyed with the translation. Instead it may conjure up quite different meanings that are not appropriate or relevant.