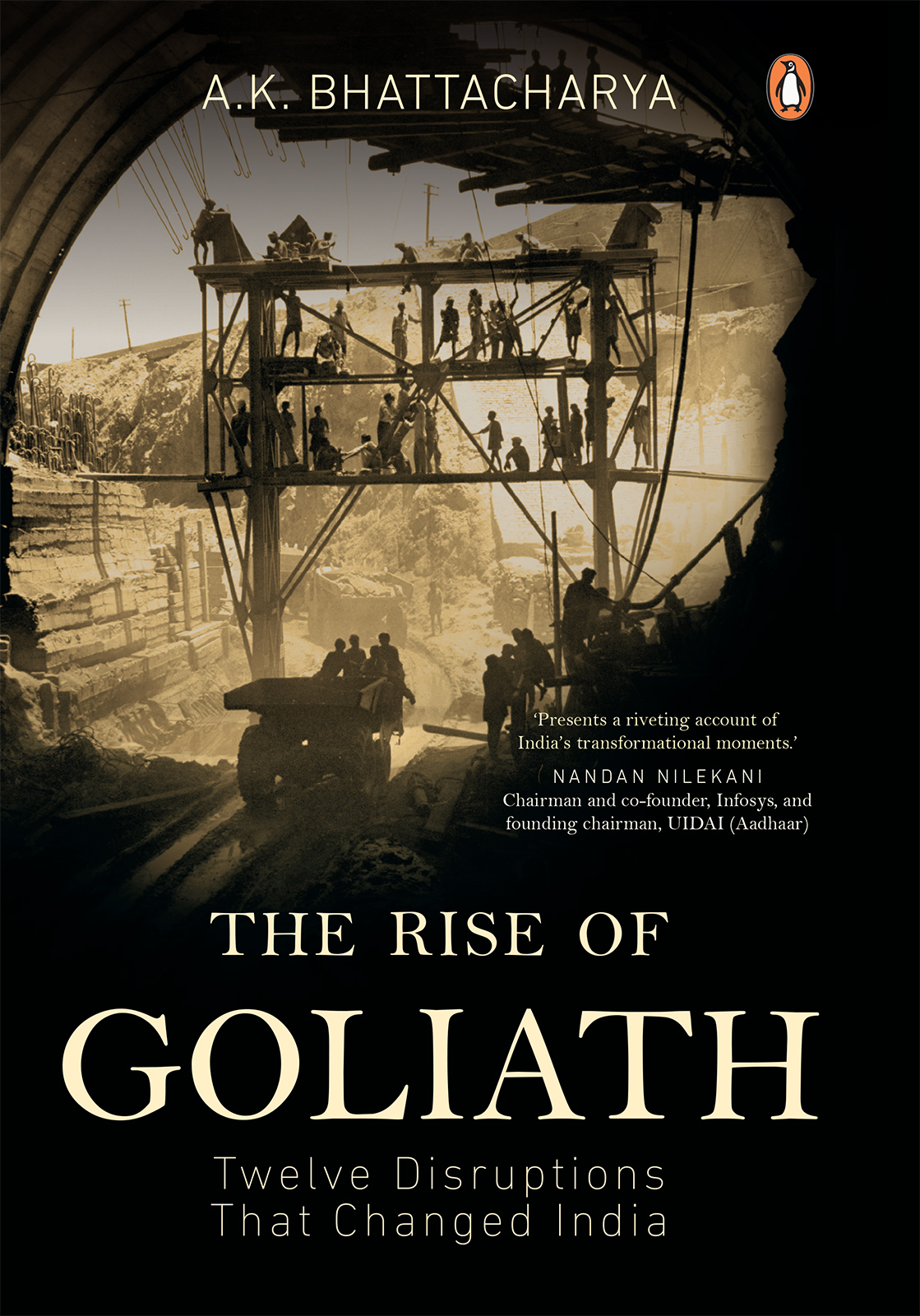

Demonetization and the GST were not the only disruptions that changed India. A.K. Bhattacharya provides a fresh perspective on many more such disruptive events that shaped India in the last seven decades. The Rise of Goliath presents a riveting account of these transformational moments.Nandan Nilekani, chairman and co-founder, Infosys, and founding chairman, UIDAI (Aadhaar)

CHAPTER 1

THE MANY FACES OF DISRUPTION

The five years of the Narendra Modi government in India have given rise to an impression that the country has seen too many disruptions in a short period of time. There was demonetization, which many people believe was the mother of all disruptions, where 86 per cent of all currencies in circulation were declared invalid in one stroke. There was the Goods and Services Tax, or GST that promised to usher in a single indirect tax across the country, replacing over twelve different central and state-level taxes and a host of surcharges and cesses. There was also the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code that ensured that promoters could lose their companies if they defaulted on repayment of loans from banks. Thanks to these disruptions, the economic landscape in India changed quite fundamentally in these five years. They have also given rise to the view that disruptions have been a hallmark of the Modi regime.

The basic premise of this book is that the Modi regime may have caused as many as three major economic policy disruptions in a relatively short period of five years, but disruptions per se have not been uncommon in Indias journey of more than seven decades as an independent country. Indeed, it can be argued that Indias journey as an independent country can be better understood if seen through the prism of disruptions. This book, therefore, will take you through a dozen such disruptions, starting right from Indias Partition in 1947 to the launch of the GST in 2017. The list is not comprehensive. There will be legitimate scope for a debate on why a certain decision has been included as a disruption and why another disruptive decision has been excluded. The purpose of the book is not to present all the disruptions that India experienced in the last seven decades or so, but to indicate the nature of a few of these disruptions and how they made a difference to Indias politics, society and economy.

It is also important to note that the disruptions captured in this book have played a significant role in the way India, like Goliath, has risen and grown in the last seven decades. Some disruptions have constrained the pace of Indias change, while others have led India to a new trajectory of faster and rapid growth. Either way, the rise of this Goliath has been defined and shaped by these disruptions. Take away these disruptions and Indias growth story could have been different.

The literature on disruptions tells us that disruptions are caused by both internal and external factors. Consequences of disruptions, however, vary depending on the nature and quality of internal or external forces. The next twelve chapters will check the validity of this argument and examine if all disruptions in India can be traced to endogenous or exogenous factors or whether some other factors were responsible for them. In the process, these chapters also answer many obvious questions about the dozen disruptions that changed India. Were all the disruptions sudden? Or did they represent an outcome of a series of developments? Were these disruptions always a planned effort or a culmination of events over which policymakers had little control? What was the politics and economics behind these dozen disruptions? Personalities behind disruptions are even more fascinating than the disruptions. Who were the key personalities directly or indirectly behind those disruptions? Some of them have played a key role in executing them, while some others may have just played along. Who were the protagonists of disruptions?

Indias Partition in 1947 is the first disruption that we discuss in this book. It was a disruption about which many Indians as also their leaders were quite ambivalent. Could the leaders have delayed the countrys freedom to prevent the partition of the country? Perhaps, yes. But it seems the top Congress leaders at that time were reluctant to take the risk of gambling on securing the countrys freedom only as a united India. For so many years they had been leading a mass movement to throw the British out of the country that they feared any further delay in gaining freedom could be counterproductive and that might even be rejected by the people. There was, thus, an element of inevitability about accepting freedom with Partition. In any case, the idea of Partition had gained currency quite a few years before it actually happened in 1947. And when it happened, it had an impact on various frontson the nature of politics that would be practised in independent India and on the domestic economy and industry. The radio address of Jawaharlal Nehru on 3 June 1947 was what gave the first clear hints to the nation that India would soon become independent, but not as an undivided country. Was Nehru the only disrupter or was Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who pressed hard for the partition of India before the British could announce Indias freedom, a bigger disrupter? Was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, too, in some ways a tacit disrupter?

The rise of statism is the second disruption that the Indian economy faced, and this became evident soon after Independence. The seeds of statism were, however, sown even before 1947. The Bombay Plan, a blueprint penned in the 1940s by leading lights of Indian industry such as Jamshedji Tata, Ghanshyam Das Birla, Kasturbhai Lalbai and Purshottamdas Thakurdas, envisaged a strong dose of government funding in key infrastructure sectors to revive the Indian economy to overcome the devastation of Partition, influx of refugees and communal riots. For Indias private sector, that blueprint was a big jolt. The first industrial policy announced in 1948 confirmed that the private sector would only play a peripheral role. The state of the newly independent India would take over the responsibility of making investments in basic infrastructure and the production of a wide range of inputs for industrial activities. The launch of the planning process; the formulation of the Industrial Policy Resolution in 1956; Nehrus ideas of building huge public sector projects and showcasing them as temples of modern India; and the nationalization of the Imperial Bank of India along with a clutch of life insurance companies and the takeover of Air India, a successful commercial airline run by the Tatas till then, were all indications of how the disruption of embracing statism played out on Indian politics and economy.