Can Islam Be French?

Princeton Studies in Muslim Politics

DALE F. EICKELMAN AND AUGUSTUS RICHARD NORTON, EDITORS

Diane Singerman, Avenues of Participation: Family, Politics, and Networks in Urban Quarters of Cairo

Tone Bringa, Being Muslim the Bosnian Way: Identity and Community in a Central Bosnian Village

Dale F. Eickelman and James Piscatori, Muslim Politics

Bruce B. Lawrence, Shattering the Myth: Islam beyond Violence

Ziba Mir-Hosseini, Islam and Gender: The Religious Debate in Contemporary Iran

Robert W. Hefner, Civil Islam: Muslims and Democratization in Indonesia

Muhammad Qasim Zaman, The Ulama in Contemporary Islam: Custodians of Change

Michael G. Peletz, Islamic Modern: Religious Courts and Cultural Politics in Malaysia

Oskar Verkaaik, Migrants and Militants: Fun and Urban Violence in Pakistan

Laetitia Bucaille, Growing up Palestinian: Israeli Occupation and the Intifada Generation

Robert W. Hefner, editor, Remaking Muslim Politics: Pluralism, Contestation, Democratization

Lara Deeb, An Enchanted Modern: Gender and Public Piety in Shi i Lebanon

i Lebanon

Roxanne L. Euben, Journeys to the Other Shore: Muslim and Western Travelers in Search of Knowledge

Robert W. Hefner and Muhammad Qasim Zaman, eds., Schooling Islam: The Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim Education

Loren D. Lybarger, Identity and Religion in Palestine: The Struggle between Islamism and Secularism in the Occupied Territories

Bruce K. Rutherford, Egypt after Mubarak: Liberalism, Islam, and Democracy in the Arab World

Emile Nakhleh, A Necessary Engagement: Reinventing Americas Relations with the Muslim World

Roxanne L. Euben and Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Princeton Readings in Islamist Thought: Texts and Contexts from al-Banna to Bin Laden

Irfan Ahmad, Islamism and Democracy in India: The Transformation of Jamaat-e-Islami

Kristen Ghodsee, Muslim Lives in Eastern Europe: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Transformation of Islam in Postsocialist Bulgaria

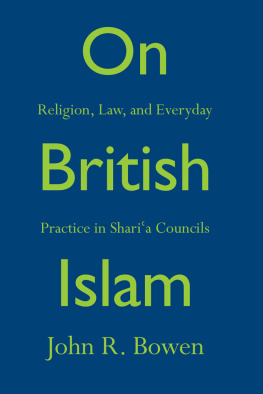

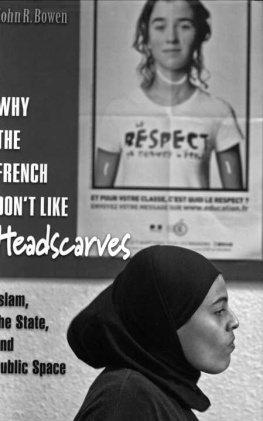

John R. Bowen, Can Islam Be French? Pluralism and Pragmatism in a Secularist State

Thomas Barfield, Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History

Emile Nakhleh, A Necessary Engagement: Reinventing Americas Relations with the Muslim World

Sara Roy, Hamas and Civil Society in Gaza: Engaging the Islamist Social Sector

Michael Laffan, The Makings of Indonesian Islam: Orientalism and the Narration of a Sufi Past

Jonathan Laurence, The Emancipation of Europes Muslims: The States Role in Minority Integration

Can Islam Be French?

PLURALISM AND PRAGMATISM

IN A SECULARIST STATE

John R. Bowen

Copyright 2010 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Third printing, and first paperback printing, 2012

Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-15249-3

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows

Bowen, John Richard, 1951

Can Islam be French? : pluralism and pragmatism in a secularist state / John R. Bowen.

p. cm. (Princeton studies in Muslim politics)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13283-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. MuslimsFrance. 2. IslamFrance. 3. Islam and politicsFrance. I. Title.

DC34.5.M87B68 2009

305.6'970944dc22 2009004645

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

To Vicki, Jeff, and Greg

Contents

Acknowledgments

I HAVE BEEN WORKING in France since 2000 and have developed close working relationships, and friendships, with many colleagues. Among those from whose example, writings, or comments I have benefited in writing this book are Valrie Amiraux, Jean Baubrot, Christophe Bertossi, Martin van Bruinessen, Jocelyne Cesari, Jacques Commaille, Jan Willem Duyvendak, Claire de Galembert, David Gellner, Ralph Grillo, Nacira Gunif-Souilamas, Christophe Jaffrelot, Baber Johansen, Riva Kastoryano, Gilles Kepel, Farhad Khosrokhavar, Jack Knight, Michle Lamont, Marie McAndrew, Ian McMullen, Franoise Lorcerie, Tariq Modood, Franoise and Jol Monger, Olivier Roy, Patrick Simon, Patrick Weil, Jean-Paul Willaime, and Malika Zeghal. Younger scholars and students often provide the most important new insights, and in my case they include Alexandre Caeiro, Yolande Jansen, and Marcel Maussen. For his critical and encouraging eye, I thank Fred Appel at Princeton University Press and his colleagues Natalie Baan and Marjorie Pannell, who expertly steered the book through production and copy editing. It is from those engaged in teaching Islam that I have learned the most; many are mentioned in the book, but here I must underscore my personal gratitude to Hichem El Arafa, Sad Branine, Chokri Hammrouni, Larbi Kechat, Dhaou Meskine, and Samia Touati for guiding my way to a better understanding of their knowledge and their challenges.

As before, I must single out Martine and Robert Bentaboulet, whose continued hospitality, lively discussions, and convivial repasts have made my time in Paris more like real fieldworkfor, as many in anthropology know, fieldwork is as much about discovering new friendships as it is about discovering new truths.

But if one holds down a day job and a day life, long-term fieldwork of the sort pursued here requires frequent travel. For making my trips financially possible I thank Washington University and the benefactors of my chair, Georgia Dunbar-Van Cleve and her late husband, Bill Van Cleve, along with generous support from the Carnegie Corporation; for making them humanly possible I thank my family, to whom the book is dedicated.

PART ONE

Trajectories

CHAPTER ONE

Islam and the Republic

MY TITLE, of course, rests on an indefensible premise. Islam cannot be exclusively French any more than it can be American or Egyptian, because its claims are universal. Although inflected and shaped by national or regional values, Islam, like Catholicism and Judaism, rests on traditions that cross political boundaries.

Let me try another way to understand the question: Can Islam become a generally accepted part of the French social landscape? Of course, it will not have the background status of Catholicism anytime soonParisians may not notice a cross or a church; they certainly notice a headscarf or a minaret. But could it become acceptedmore or less grudgingly, more or less intuitivelyas one among many normal components of the normal social world? Quick off the mark there are signs that suggest yes, perhaps, and others that indicate no, maybe not.

Among the positive signs: A 2006 survey found that French people as a whole think Islam can fit into France. When asked if there is a conflict between being a devout Muslim and living in a modern society, 74 percent of all French people said no, there was not. Only about half as many other Europeans or Americans deny such a conflict. Indeed, French people are more positive about modern Islam than are people in Indonesia, Jordan, or Egypt! This positive answer may be related to an equally hopeful finding of the survey: French Muslims are about as likely to emphasize their national identity over their religious one as are U.S. Christiansand they are much more likely to do so than are other European Muslims. So, at least when talking to pollsters, goodly numbers of French Muslims and non-Muslims seem to think that Islam could be French.

i Lebanon

i Lebanon