JOHN R. BOWEN

To my parents, for a lifetirue of love and support

ix

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 34

CHAPTER 65

CHAPTER 98

CHAPTER 128

CHAPTER 155

CHAPTER 182

CHAPTER 208

CHAPTER 242

IN the introduction I acknowledge my intellectual debts, but here I wish to thank those who have shared their time, their thoughts, their experiences, their friendship; they include Marc Abeles, Fariba Adel- khah, Valerie Amiraux, Jean Bauberot, Didier Bourg, Said Branine, Jocelyne Cesari, Hanifa Cherifi, Jacques Conmiaille, Catherine Coroller, Hichem El Arafa, Hakini El Ghissassi, Claire de Galembert, Virginie Giraudon, Ghislaine Hudson, Christophe Jaffrelot, Riva Kastoryano, Larbi Kechat, Gilles Kepel, Farhad Khosrokhavar, Illhaou Meskine, Olivier Roy, Patrick Sinion, Sarnia Taouati, Xavier Temissien, Patrick Weil, Jean-Paul Willaime, and all those, cited in the text, who taught nie about France. Fariba Adelkhah, Christophe Jaffrelot, Jean-Francois Bayart, and Gilles Kepel made possible a visiting professorship at the Institut des Sciences Politique in 2001 that allowed me to begin work on these questions, and they along with Riva Kastoryano have continued to make it possible for nie to work in Paris, as has a more recent collaboration with the Ecole Pratiques des Hautes Etudes through the good graces of Jean-Paul Willaime.

In France, however, it is above all Martine and Robert Bentaboulet who, by inviting nie to join their family and engaging in endless discussions on the issues covered here, have made fieldwork both possible and much more than fieldwork. Such are the joys of anthropology, the continuing friendships of those whom we come to know as well as we do anyone in our "home" countries.

At Washington University I benefit from a wonderful and supportive scholarly environment and from the support of Georgia Dunbar Van Cleve and her late husband Bill. These traditions of beneficence for scholarship are one of our society's strengths. Many of my colleagues, too numerous to name, have given me comments and suggestions over the years. I have benefited from the opportunity to present portions of this book during 2004-2005 at Cornell University's Law School, at Stanford University's Department of Cultural and Social Anthropology, at Georgetown University's French Department, at Amsterdam University to members of the EU IMISCOE network, and in Paris to the International Congress of the Sociology of Law. I learned a lot from comments by anonymous readers of the manuscript and by my dedicated and perceptive editor at Princeton University Press, Fred Appel. The manuscript benefited enorniously from conscientious and professional editing by Madeleine B. Adams and production editing by Meera Vaidyanathan.

My wife, Vicki Carlson, and sons, Jeff and Greg, have graciously understood my absences and, joyfully for me, accompanied me for some travel to France. Their love sustains me.

My parents made it possible for me to grow, learn, live, and, eventually, teach and write. To them this book is dedicated.

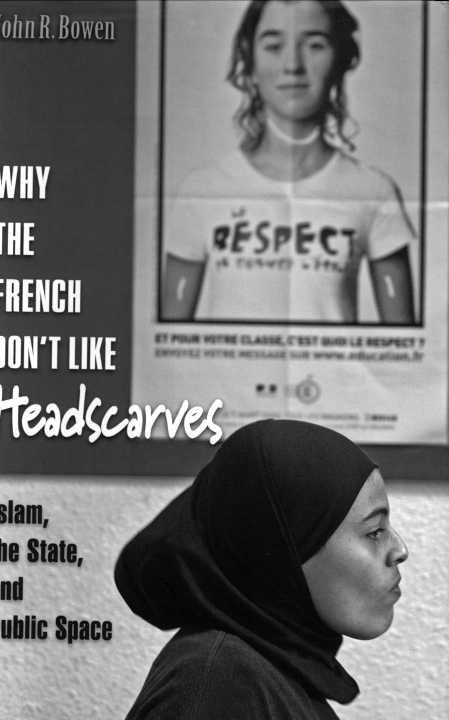

IN EARLY 2004, the French government passed a law prohibiting from public schools any clothing that clearly indicated a pupil's religious affiliation. Although worded in a religion-neutral way, everyone understood the law to be aimed at keeping Muslim girls from wearing headscarves in school. The law was based on recommendations issued in late 2003 by two prestigious commissions, one formed by the Parliament, the other appointed by President Jacques Chirac (the Stasi Commission). Their hearings and the media coverage of the issue depicted grave dangers to French society and its tradition of secularism (laicite) presented by Islamic radicalism, a trend toward "communalism," and the oppression of women in the poor suburbs. Although some Muslims objected that the proposed law would violate their right to express religious beliefs and many observers doubted that a law banning scarves would seriously address the severe problems of integration in French society, the two commissions voted with near-unanimity for the law, and the measure passed with large majorities in the National Assembly and in the Senate. It went into effect in September 2004.

The debate and votes perplexed many observers. French public figures seemed to blame the headscarves for a surprising range of France's problems, including anti-Semitism, Islamic fundamentalism, growing ghettoization in the poor suburbs, and the breakdown of order in the classroom. A vote against headscarves would, we heard, support women battling for freedom in Afghanistan, schoolteachers trying to teach history in Lyon, and all those who wished to reinforce the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Given that relatively few disputes over scarf-wearing ever went beyond the classroom and that virtually no one accused scarf-wearing girls of presenting a serious danger to French society, why was a law that would force them to choose between leaving their scarves at home or leaving school be seen as such a broad palliative for France's social ills and such an important step for women everywhere? Why focus on this issue above all others? The French actions puzzled most of the world; many people saw it as at best a misplaced concern and at worst a violation of religious freedom.

It seemed to me that the law, and its broad support, should be explained. I realized that doing so would require unpacking a great deal about France, including France's very particular history of religion and the state, the great hopes placed in the public schools, ideas about citizens and integration (and the challenge posed by Muslims and by Islam to those ideas), the continued weight of the colonial past, the role of television in shaping public opinion, and the tendency to think that passing a law will resolve a social problem. I would then need to show how all these dimensions of French memory, society, and ways of thinking combined to move the political machinery toward passage of a law during 2003-2004. But I also wished to see what we could learn about France from the debates over the law. It seemed to me that its passage was one of those key moments in a country's life at which certain anxieties and assumptions come to the surface, when people take stock of who they are and of what kind of social life they wish to have.