PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright 2016 John Boyko

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2016 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto, and in the United States of America by Penguin Random House, New York.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Alfred A. Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Cold fire : Kennedys northern front / John Boyko.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-345-80893-6

eBook ISBN 978-0-345-80895-0

1. Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962. 2. United StatesHistory19611969. 3. United StatesPolitics and government19611963. 4. Kennedy, John F. (John Fitzgerald), 19171963. 5. United StatesForeign relationsCanada. 6. CanadaForeign relationsUnited States. 7. CanadaHistory19451963. 8. CanadaPolitics and government19571963. 9. Diefenbaker, John G., 18951979. 10. Pearson, Lester B., 18971972. I. Title.

E841.B69 2016 973.922 C2015-905781-7

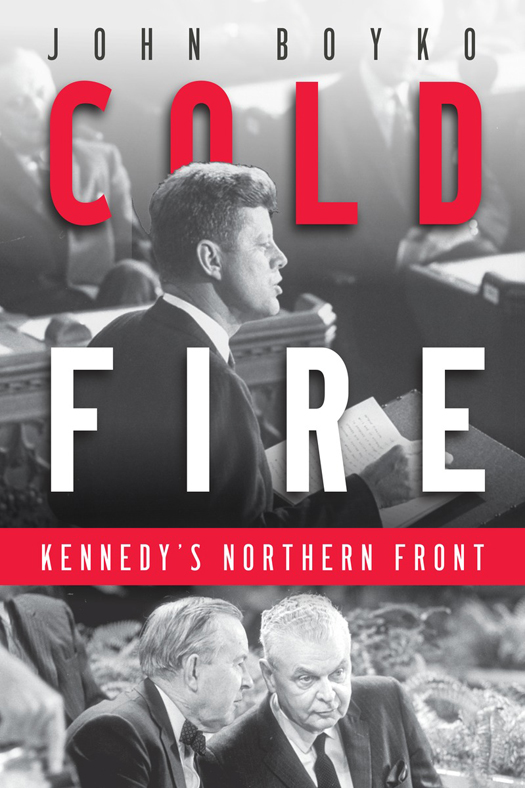

Cover images: (Lester Pearson and John Diefenbaker) John McNeill / The Globe and Mail / The Canadian Press; (John F. Kennedy) Paul Schutzer / The LIFE

Picture Collection / Getty Images

v3.1

This book is for Sue.

Never has the task of finding the truth been more difficult.

JOHN F. KENNEDY, MONTREAL, DECEMBER 4, 1953

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

THERE WAS NO CROWD AT THE AIRPORT . There were no reporters. Although the 1960 presidential election was three years away, Senator John F. Kennedy had been vigorously campaigning, and so he must have found his silent arrival in Toronto on that slate grey November afternoon either amusing or disconcerting. Throughout 1957 he had been a frequent and entertaining guest on American political chat shows. His office flooded newspapers and magazines with press releases and articles he had written or at least edited. He accepted 140 speaking engagements. The Herculean effort to render his already famous name even more so had spilled over the border, as these things do. By the time of his visit, Canadians knew of him and his ambition.

Twenty female University of Toronto (U of T) students certainly knew. They were waiting outside Hart House, where Kennedy was scheduled to participate in a debate. Since its opening in 1919, Hart Houses lounges, library, and recreational facilities had become the universitys social and cultural hub. The impressive Gothic revival building was a gift from the Massey family that had made its fortune in farm machinery. It was named for company founder Hart Massey and dedicated by his grandson, Vincent, who would later become the countrys first Canadian-born governor general. He insisted on guidelines stipulating that within its stone, ivy-covered walls, Hart House would allow no studying, drinking, or women. The first two rules were often and flagrantly broken, but Margaret Brewin, Judy Graner, and Linda Silver Dranoff led a contingent hoping to end the third. They asked the Hart House warden to allow women to see the debate. When rebuffed, they gathered friends, created placards, and greeted Kennedy with chants that alternated between Hart House Unfair and We Want Kennedy.

Kennedy smiled but said nothing as he was escorted through the drizzling rain and noisy protesters. Beneath its towering, dark oakpanelled ceiling, the Debates Room could seat two hundred and fifty. It was packed. A scuffle interrupted introductions when a sharp-eyed guard noticed a guests nail polish and removed three women who had snuck in disguised as men. With the women locked out, the men inside prepared to argue: Has the United States failed in its responsibilities as a world leader? Kennedy was given leave to present remarks from the floor in support of the team defending American actions.

Reading from a prepared text, he offered that Americans did not enjoy immunity from foreign policy mistakes but that the difference between statesmanship and politics is often a choice between two blunders. He expressed concern regarding the degree to which public opinion sometimes dictated sound public policy and admitted that the United States had misplayed some recent challenges in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Regardless of these and other errors, he argued, American foreign policy rested on sound principles and his country remained a force for good.

The address was well written but poorly delivered. Kennedy read in a flat tone and seldom looked up.

The audience gasped in disbelief when adjudicators scored the debate 204 to 194 in favour of Kennedys side. Afterwards, at a participants reception, Lewis spoke with Senator Kennedy and expressed confusion as to why a Democrat such as he would defend the hawkish policies of the current Republican administration. Kennedy startled Lewis by confessing that he was a Democrat only because he was from Massachusetts and that if he were from a predominantly Republican state such as Maine, he would probably be a Republican.

Kennedy was not through raising eyebrows. When leaving Hart House, a reporter asked his opinion of the womens demonstration. He smiled and said, I personally rather approve of keeping women out of these places. Its a pleasure to be in a country where women cannot mix in everywhere. Although victorious, Kennedy had impressed few with his speech, fewer with his confession of political opportunism, and fewer still with his flippant dismissal of women and the concept of gender equality. His brief meeting with a small group of the protesting women the next morning changed no minds. Kennedys Toronto flop was surprising; by 1957 he had become quite adept at handling gatherings that demanded a blend of political chops and charm.

He returned to his campaign and the students to their studies, but the brief visit had hinted at important questions soon to be asked in forums more significant than a student debate. On the day Kennedy visited Toronto, John G. Diefenbaker was Canadas prime minister and Lester B. Pearson was positioning himself to win the leadership of the opposition Liberals. The three leaders would soon meet at a crossroadsone that would determine the nature of Canadas independence, Americas struggle against communist aggression, and the art and science of leadership itself in a new era of television and political celebrity.

The important decisions would be made while everything that had been certain for so long seemed to be changing. In 1957, economic growth on both sides of the border had fallen from a decade of 6 percent per year to an anaemic 1 percent. The good times that many had come to believe would never end were ending. Popular culture was changing. Rock n roll and the Beat movement were leading many young people (and the young at heart) to question established values. Race relations were changing, as evidenced by Americas non-violent civil rights protests and Diefenbakers pledge to create a Bill of Rights and afford Native people the vote.