Dahlqvist masterfully moves between storytelling and frameworking how stigma holds menstruators back globally, while offering tangible solutions to many of these problems. A must read.

Kiran Gandhi, musician, activist, and free-bleeding runner at the 2015 London Marathon

An eye-opening and necessary book that will challenge your assumptions. Thought provoking, relevant and sensitively written.

Chella Quint, founder of #periodpositive

Brilliant. It was frustrating to realise how much there is to be done, but also inspiring to read about these groups of women all over the world working bloody hard toward the same ideal: that periods do not need to stand in the way of an education, a future, or a good life.

Gabby Edlin, founder of Bloody Good Period

Only when we call out the unnecessary shame and stigma that surrounds periods can we demand meaningful change. Dahlqvists deft, compassionate storytelling, and her critical global perspective, are a tremendous contribution.

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf, author of Periods Gone Public: Taking a Stand for Menstrual Equity

An insightful and inspiring read that will challenge you to think and behave differently.

Mandu Reid, founder of The Cup Effect

A lushly detailed and often intimate portrait of a global social movement. Whats more, Dahlqvists perceptive account reveals the insidious power of stigma to limit lives.

Chris Bobel, author of New Blood: Third-Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation

A wide-ranging exploration of the enduring taboos surrounding menstruation, taking the author around the globe. What she uncovers in this provocative and insightful book will make us forever rethink our first world problems by putting periods in a global context.

Karen Houppert, author of The Curse: Confronting the Last Unmentionable Taboo

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Anna Dahlqvist is a journalist specialising in gender, sexuality and human rights. She is editor-in-chief of Ottar , a Swedish magazine focusing on sexual politics, and has previously published a book on illegal abortion and abortion rights in Europe.

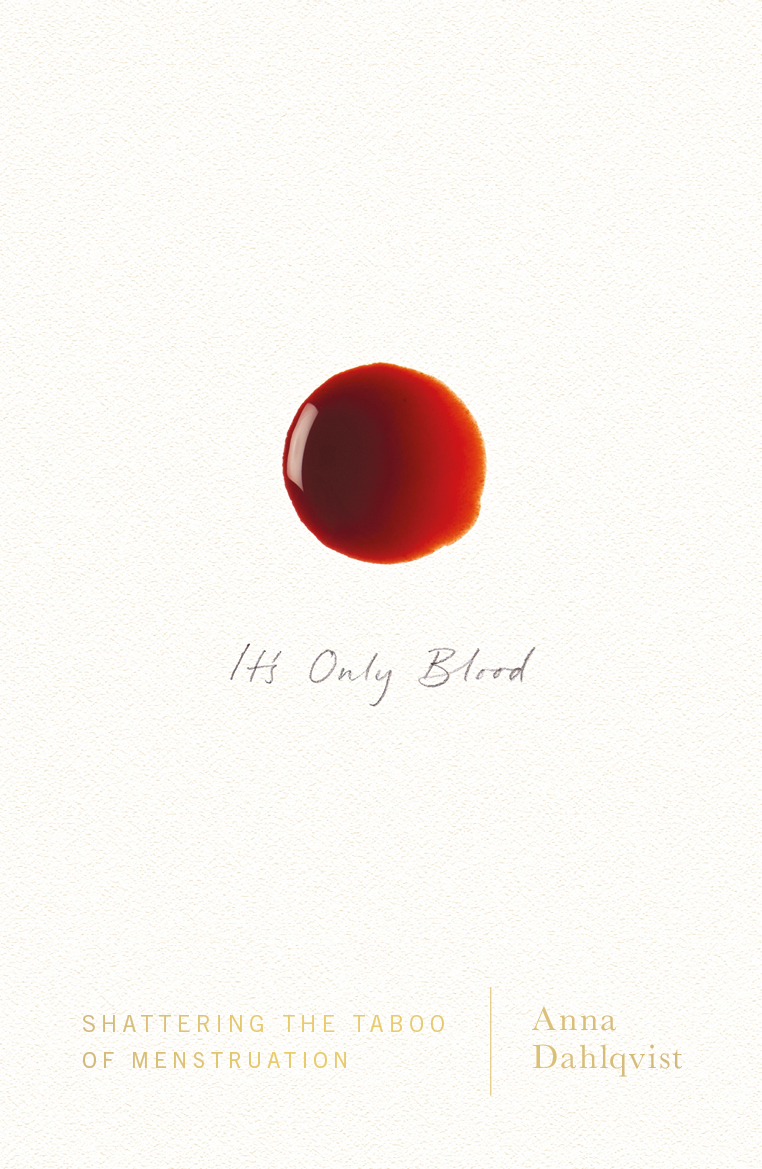

Its Only Blood

SHATTERING THE TABOO OF MENSTRUATION

ANNA DAHLQVIST

TRANSLATED BY ALICE E. OLSSON

Dont you get angry when the boys laugh and tease you?

No.

But why not?

Theyre laughing because the girls cant keep themselves clean.

It is said as a matter of course, a simple stating of facts. Those who laugh are not doing anything wrong. The girls with the blood stains are. They simply have themselves to blame if they fail to hide the menstrual blood. If they cannot keep themselves clean.

Saudah herself has never been in that situation, never stood shameful in front of the others in the classroom. But she is well aware of the risk and of her own responsibility. Every month, she tries hard to make sure that the blood, which so persistently demands attention, remains invisible.

That it is private, not something that should be noticed or that she should talk about, was one of the two things she first learned about menstruation. The other was that she has to stop spending time with boys when she gets her first period. The importance of secrecy and of staying away from boys. I will hear it again as a whisper, a sharp admonition, a self-evident piece of information.

* * *

Fourteen-year-old Saudah lives in Bwaise, one of the poorest areas in the Ugandan capital, Kampala. She is sitting in the schoolyard shade. It is an awkward situation for her as for any other teenager. Much of what Saudah feels and thinks about menstruation she will probably keep to herself. I can expect fragments, filtered through the demand for secrecy. She does not want her auntie, the adult relative she lives with, to find out what we are talking about. As long as the principal of the school is listening curiously nearby, Saudah replies dutifully, though in monosyllables.

The chorus from the classroom for the youngest children breaks the silence over the empty yard, a small patch of trampled, rock-hard orange sand. Land is a hard currency here in Bwaise, which is known for extensive trafficking in sex and drugs. Many people live on less than 1 US dollar per day. That is also the price of a pack of eight menstrual pads in Kampala. An estimation of how much that would be for me: around 100 US dollars. Would I pay that? I dont think so. In Sweden, the price of eight menstrual pads corresponds to roughly 2 US dollars.

Saudah is wearing a school uniform with a purple polo shirt, striped tie, and dark blue skirt. She measures carefully against the skirt to show the size of the pieces of cloth she uses as menstrual protection. When she got her first period two years ago, she cut them out from an old dress. It was dark blue, just like the skirt. She folds the fabric in several layers to make sure it will hold the blood and winds it around the seat of her panties, to make it stay in place. Her nightmare is not just that it might leak, but also that the bloody cloth could fall out from under her skirt. That it could land on the concrete floor in the classroom or on the hard sand in the schoolyard.

She wishes fervently that her auntie would give her money for disposable sanitary pads.

Ive asked several times, but she just says no. Its impossible.

Saudahs mother lives in the countryside, her father is dead, and her auntie provides for Saudah and her brother with money sent from the family.

The purchased disposable pads, many of the same brands as the ones sold in stores in Europe, have an adhesive on the bottom and on the sides or wings. The pads are only a few millimetres thick, made of cellulose that absorbs liquid. They do not need to be washed and dried.

It would be so much simpler, says Saudah, who after the first guarded answers is speaking more freely about the hassle with the cloth and the disposable pads she longs for.

The principal has gone back to the office.

When Saudah is on her period, she walks home during the lunch break. She gets water from the pump in the yard, which is surrounded by two rows of houses accommodating more than 50 people. One room per family. Behind one of the buildings, two communal latrines are located. She prefers not to walk there in the evening or at night, as the risk for sexual violence becomes very real when darkness falls over Bwaise. They have a bucket for emergencies.

She brings the water into the room where she lives with her auntie and brother. If she is lucky there is soap at home, but usually not. Sometimes she borrows soap from a neighbour. Carefully, to avoid getting blood on her thighs, she removes the cloth that she has wound around the seat of her panties. She then scrubs the fabric as best she can to remove the blood. It is stubborn; blood clings hard to textiles. And it is difficult to see whether the fabric is clean. The lighting is poor and the room only has one small window. Saudah puts the cloth on a hanger inside the house, somewhere it cannot be seen. Behind a piece of clothing or under the bed. Carefully, she winds a new piece of cloth around her panties before walking back to school.

When I ask how she feels about the cloth, she does not turn to the two interpreters. She looks directly at me and replies in English rather than her native language, Luganda: I feel bad. Thats it.

I feel bad turns out to mean much more than that it is lumpy, uncomfortable and wet, as Saudah says, because the fabric does not soak up the blood very well. The bad is mainly about the fear. What if.