Table of Contents

For Colin

At the request of some individuals mentioned in this work, the author has changed their names and, in some instances, omitted identifying characteristics.

Introduction

THE BETTER MOUSETRAP

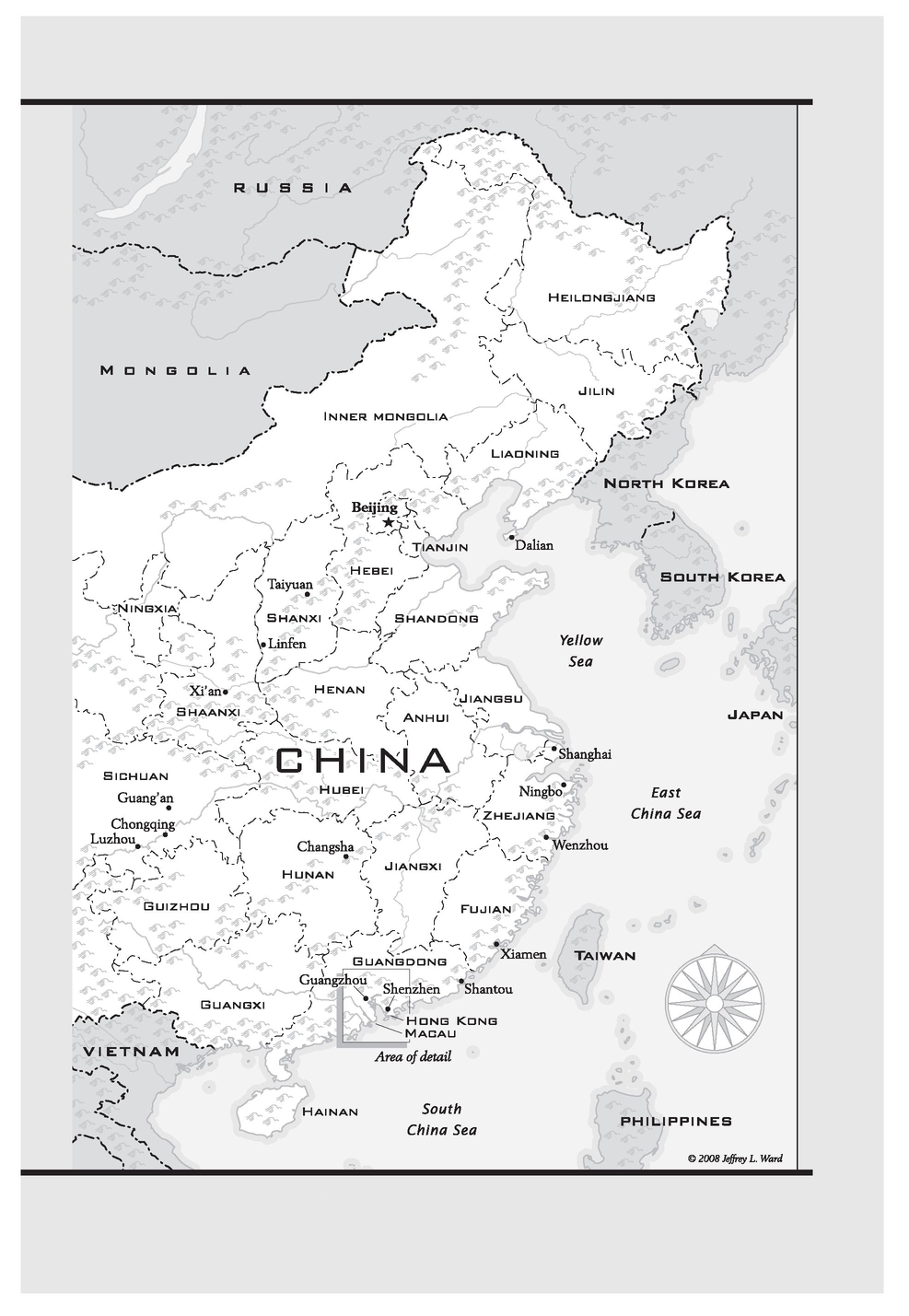

FOR TWO WEEKS twice a year, trains and planes to the Chinese city of Guangzhou swell to capacity with crowds of foreign men and women. Hundreds of thousands of these people, representatives of the worlds importers, fill the citys hotels, bars and restaurants with a babel of Japanese and Arabic and English and French. Every morning, they pile onto shuttle buses and head straight for one of the citys two colossal convention centers.

Theyve come to pay homage to one thing: the China price.

Inside the many massive halls of the convention centers are thousands of companies peddling countless products made in China. Sweaters, showers, power drills, plates, jacuzzis, cell phones, SUVs, plastic neon palm treeseverything, including the kitchen sink, all for half or even a fifth of what it would cost to make in America.

Over the last several years, the China price has redrawn the global manufacturing map and laid the foundation for the next economic superpower. It has put legions of people out of work around the world and become an open wound in international trade relations. And it has brought unprecedented change to the lives of hundreds of millions of Chinese.

Cheap Chinese goods have made shopping more affordable. By one estimate, products made in China have saved the average American family $500 a year.

The China price touches everyone, everywhere. Since the start of the new millennium, China has come to dominate global manufacturing in a way almost inconceivable before its rise. The prices it offers have been so low that starting around 2003, they have become known simply as the China price.

In August 2007, Mattel recalled millions of toys made in China because of concerns about their safety. Its announcements that some of its toys contained paint with excessive levels of lead and others included dangerously small magnets touched off a global wave of concern about the quality of Chinese-made goods.

The United States has banned the import of certain types of farm-raised seafood from China because of fears that it may have been contaminated with drugs and other chemicals. Chinese-made tires and toothpaste have come under scrutiny. And traces of pollution from Asia, undoubtedly much of it from China, have been detected on the west coast of America.

Yet beyond the headlines about job losses and product safety scares, what is it we really know about Chinas manufacturing juggernaut?

The aim of this book is to uncover the true cost of Chinas competitive advantage. Who are the people behind the China price? How do they make goods so cheaply? At what cost to them, and to us? And how long can they keep it up?

OVER THE LAST DECADE OR SO, China has become legendary for its ability to undercut prices for everything from consumer goods to industrial machinery. The only way for manufacturers elsewhere to compete was to move to China themselves. As a writer for Fortune magazine put it in March 2002, any CEO worth his salt these days is deciding not whether to move manufacturing capacity to China but how much and how quickly.

China makes you sharp or it kills you, the Wall Street Journal quoted Eslie Sykes, manager of a Flextronics plant in Guadalajara, Mexico, as saying.

The China price has, in effect, become a brand. To most people, its brand image is a collage: cheap clothing and electronics filling the shelves at Wal-Mart, factory workers at home losing their jobs, the woman on the jacket of this book.

To executives, the China price stirs fears of a new competitor in the East but also conjures soothing visions of hefty savings. To politicians, the term has become shorthand for unfair trading practices including an undervalued currency, intellectual property violations and dumping of cheap goods. To scholars, the China price has become part of a debate on the merits of unfettered trade. And to journalists like me, the China price has looked like a giant, creaking tectonic plate, shifting the way the world thinks about the delicate balance of global trade and national good.

The debate over imports and their effect on the domestic economy isnt new, of course. American companies have been moving manufacturing offshore for decades, and American workers have understandably been upset about it for almost as long. But never has one country yielded such visible price declines on such a wide range of goods in such a short period of time. It is as though the world has been watching a second industrial revolution unfold.

Over the past two decades, Chinas share of global manufacturing, measured in terms of value added, has risen faster than that of any other country. Its share of the worlds manufacturing output by value added was 2.4 percent in 1990; by 2006, that share had grown to 12.1 percent, making China the worlds third-largest producer after America and Japan.

Chinas exports have been posting double-digit annual growth, on average, since the 1990s. China went from exporting $26 billion worth of goods to the world in 1984 to exporting $969 billion in 2006. Global Insight, a U.S. economics consultancy, expects China to overtake the United States as the worlds largest manufacturer in 2020. If current trends continue, China will surpass America to become the largest exporter in the world in 2008.

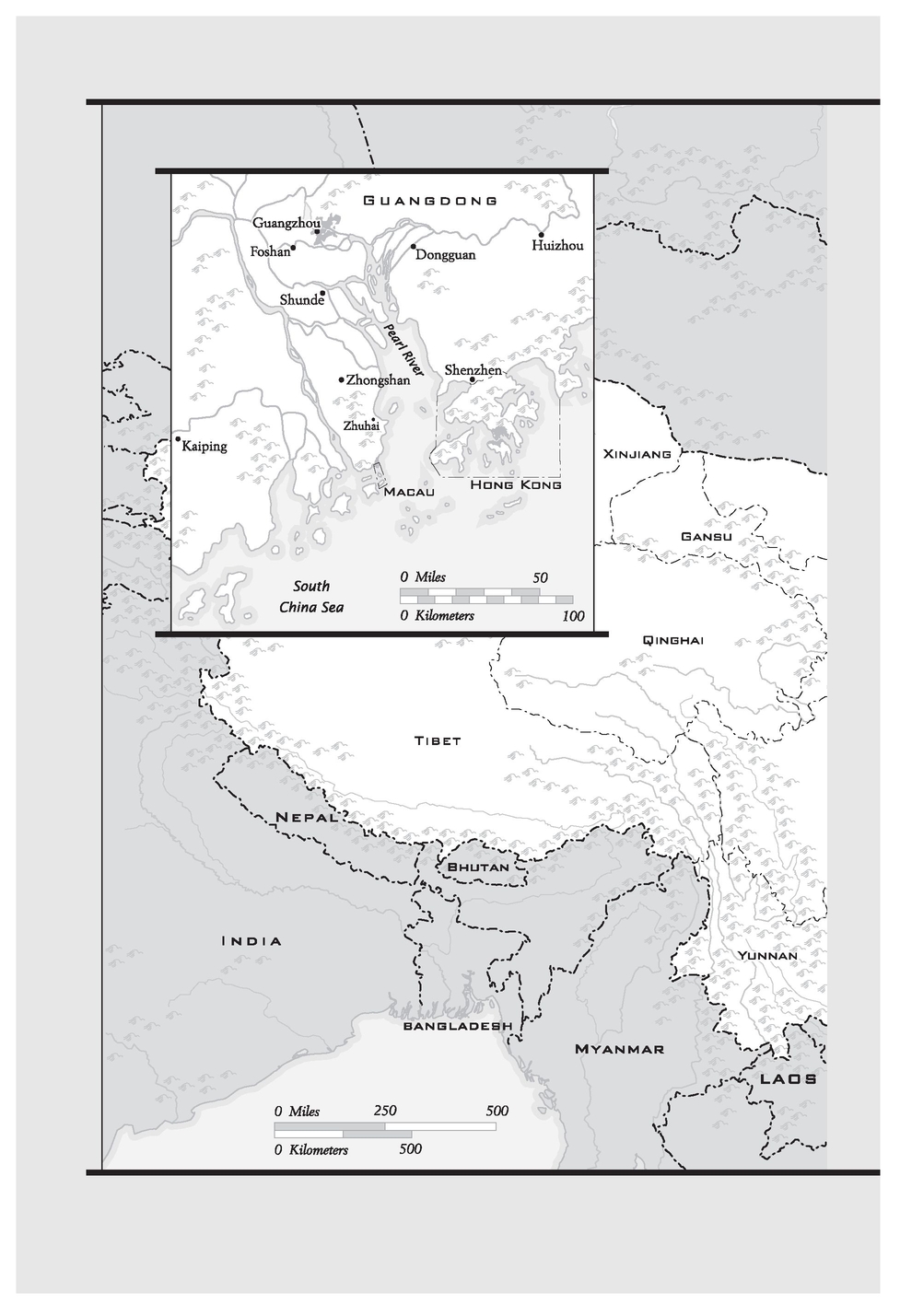

China has challenged the conventional theory of comparative advantage by making everything from basic consumer goodsthe shoes, clothing and toys that other Asian countries produced during their export boom years after World War IIto higher-tech products like computer screens, iPods and cell phones. Much of this success is due to the marriage of Chinese labor with foreign capital. Chinas courtship of international business has drawn the worlds manufacturers to its doorstep. Southern cities like Guangzhou, Dongguan and Shenzhen are filled with Indians, Brazilians, Japanese, Israelis, Brits, Irish, Italians, French and Americans who have moved to China to open their own factories or sell Chinese-made goods overseas. Wal-Marts global sourcing center is based in the southern city of Shenzhen, just across the border from Hong Kong. IBMs chief procurement officer sits in Shenzhen as well.

In 1990, China attracted $3.5 billion of foreign direct investment. By 2005, that figure had soared to $72 billion, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Cumulative foreign direct investment in China between 2002 and 2005 alone totaled $239.28 billion. That investment has helped produce the facilities that comprise the workshop of the world. Wal-Mart buys at least $18 billion worth of goods from China every year. Samsung bought $15 billion worth of supplies there in 2005.

In 2006, Chinas biggest exports by volume to America were electrical machinery and equipment, including consumer electronics and power generation equipment. But it also shipped a lot of toys and sporting goods, clothing, furniture and shoes. That year, America imported $287.8 billion worth of products from China. Americas exports to China totaled only $55.2 billion.