Marc Levinson - Outside the Box

Here you can read online Marc Levinson - Outside the Box full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

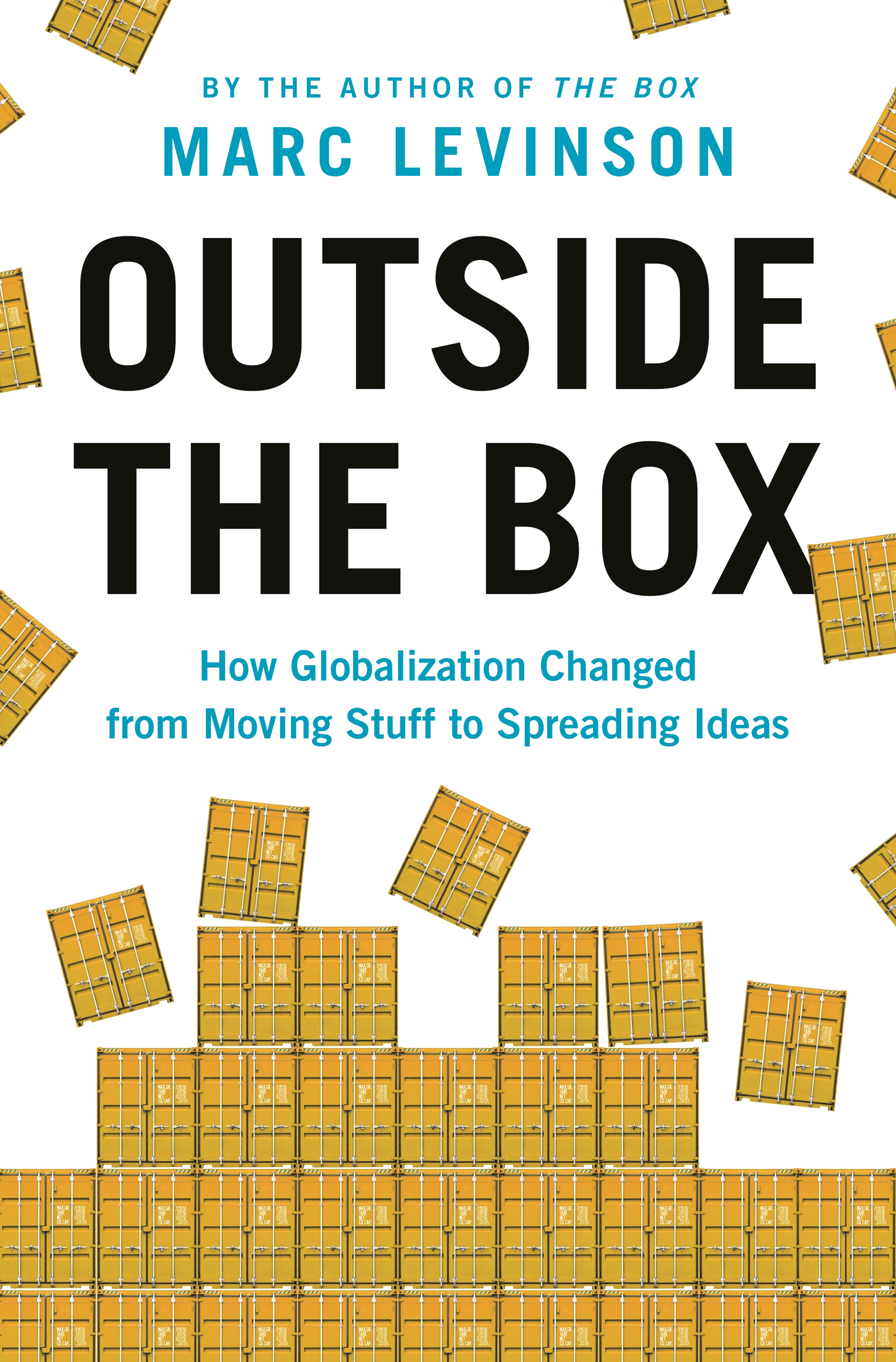

- Book:Outside the Box

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Outside the Box: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Outside the Box" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Outside the Box — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Outside the Box" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

OUTSIDE THE BOX

Outside the Box

HOW GLOBALIZATION CHANGED FROM MOVING STUFF TO SPREADING IDEAS

MARC LEVINSON

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON&OXFORD

Copyright 2020 by Marc Levinson

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-19176-8

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-20583-0

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Joe Jackson and Jacqueline Delaney

Production Editorial: Jenny Wolkowicki

Jacket design: Karl Spurzem

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Kate Farquhar-Thomson and James Schneider

Copyeditor: Maia Vaswani

Jacket image: Shutterstock

ON AUGUST 16, 2006, at five thirty in the afternoon, five tugboats dragged Emma Maersk from the Odense Steel Shipyard and towed her backward to the sea. Whether new or old, ships generally sail forward, not backward, but there was nothing typical about Emma Maersk. The length of four soccer fields, her keel nearly a hundred feet below her deck, the light blue vessel was so enormous she could barely escape the confines of the shallow Odense Fjord. As she passed through the Gabet, the narrow gap between the fjord and the deeper waters beyond, the thousands of Danes lining the beaches were treated to an extraordinary sight. On her launch day, because Emma carried neither cargo nor fuel, she rode high in the water, partially exposing her white underside and showing off the massive bronze propeller that would normally turn silently beneath the waves. It was, as everyone knew from news reports, by far the largest propeller ever cast.

Emma Maersk was a bet on globalization. Owned by Maersk Line, part of a venerable Danish conglomerate, she dwarfed every vessel that had preceded her in the fifty-year history of container shipping. Save for a handful of oil supertankers, there had never been a ship so large. Emma and the seven similar ships that were to follow cost $154 million apiece, much more than any containership had cost before, and the price seemed a bargain. If the new vessels were loaded to capacity, they would be able to transport the worlds trade more cheaply than any other ships afloat. As the world economy expanded and long-distance trade increased with it, Maersk Lines leaders expected, that cost advantage would enable their company to capture a growing share.

Containerships are the workhorses of globalization, carrying steel boxes stuffed with everything from washing machines to waste paper vast distances on regular schedules, meshing with trucks, trains, and barges to serve cities miles inland. International cargo that is time sensitive or highly valuablediamonds, disc drivesusually flies across the oceans, but almost everything else churned out by factories and much that comes from farms is packed into standard containers forty feet long and eight feet across. In the final decades of the twentieth century, containers all but erased transportation costs as a factor in decisions about where to make things, where to grow things, and how to move goods to customers. They helped reshape world trade, making it feasible to combine parts from a dozen countries into a finished car and delivering wine from Australia to California, a distance of seven thousand miles, for perhaps fifteen US cents a bottle. They lay behind the startling transformation of China into the worlds largest manufacturing nationand behind the desolation of long-standing manufacturing centers, from Detroit to Dortmund, as distinct national markets, protected by high transportation costs, merged into a nearly seamless global one.

Since the first containership steamed from Newark to Houston in 1956, each generation of vessels had been larger and more cost-effective than its predecessors. Emma and her sister ships were commissioned in the expectation that this trend would continue, making it even easier for families to enjoy fresh strawberries in wintertime and enabling manufacturers to weld longer, more complex supply chains linking factories and distribution centers thousands of miles apart. Dozens of even larger ships would soon follow in Emmas wake, some able to carry more cargo than eleven thousand over-the-road trucks. But just as a race to build monumental skyscrapers often heralds an economy poised for a correctionthe Empire State Building in New York, planned in the late 1920s to be the worlds tallest building, sat largely empty through the Great Depression of the 1930sso the construction of ships too big to call at most of the worlds ports was an early indicator of excessive exuberance. Unremarked at the time of Emma Maersks launch, the era of ceaseless growth in goods trade was about to draw to a close. Those who assumed that globalization would stay on the course it had followed since the aftermath of World War Two would pay a steep price.

Globalization is not a recent concept. The word seems to have made its first appearance in Belgium in 1929: physician and educator J. O. Decroly used globalization to refer to a young childs developing attention to the broader world rather than itself alone. Over time, the term has had many other meanings: the idea that giant companies can sell the same product everywhere rather than different models in each country; the transmission of ideas from one country to another; the flag-waving enthusiasm of Americans and Kenyans and Chinese for English soccer teams led by non-British stars. The worldwide diffusion of religions is a form of globalization, as are the spread of disease and the large-scale migration of people in search of personal safety, political or social freedom, or greater economic opportunity. So, of course, is the increasing intensity of economic exchange across international frontiers.

The world was in some ways highly globalized long ago; as the historians Jrgen Osterhammel and Niels P. Petersson put it, In a certain sense, the Americanization of Germany did not begin in 1945 but rather in the eighteenth century, with the introduction of the potato. But globalization, as that term is used today, erupted with the birth of industrial capitalism in the nineteenth century, as Europes colonial powers spun commercial webs across Africa and Asia, protecting their interests with armies, navies, and professional corps of colonial civil servants. Erstwhile manufacturing centers, notably India, were unable to match the higher productivity of European factories, and as their textiles became uncompetitive with foreign products, they sank into the role of commodity exporters. During this First Globalization, international lending was routine, and in many countries exports and imports accounted for large shares of economic activity. Migrants crossed borders by the tens of millions, and motifs from China and Tahiti found their way into European art. The world seemed to have become so interconnected that war was impossibleuntil the eruption of World War One in August 1914 brought the First Globalization to an abrupt end.

The process of globalization paused from 1914 until roughly 1947, through two world wars, numerous regional wars, and a great depression. While multinational corporations expanded during those years, many of the financial, commercial, and human links across borders eroded. In some quarters, this retreat was welcomed; in 1943, the US congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce criticized Vice President Henry Wallace, who prided himself on his global perspective, for spouting globaloney. After much criticism, Luce abandoned the term in favor of global nonsense. But in the wake of her coinage, words such as globalistic, globalitis, and globalism made their way into the American vocabulary, being employed to disparage immigration, foreign trade, and even proposals for international cooperation.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Outside the Box»

Look at similar books to Outside the Box. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Outside the Box and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.