CONSTITUTIONAL FAITH

SANFORD LEVINSON

Constitutional Faith

With a new afterword by the author

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 1988 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

First printing, 1988

First paperback printing, 1990

Paperback reissue, with a new afterword, 2011

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011925345

ISBN: 978-0-691-15240-0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Linotron Caledonia

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

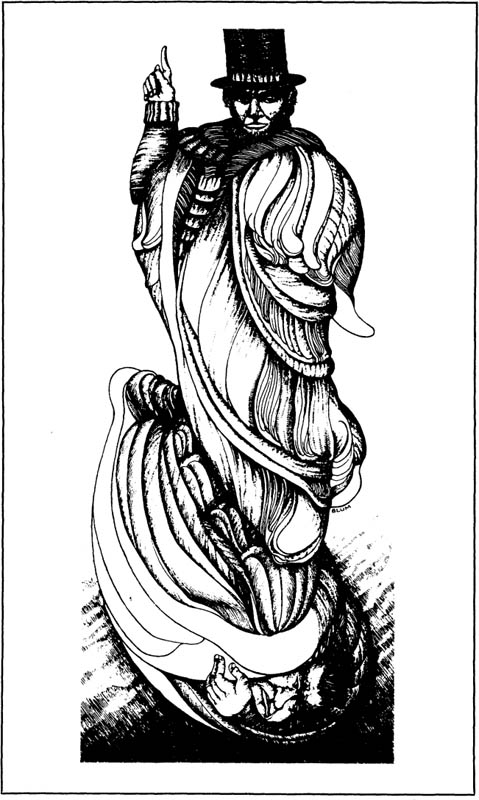

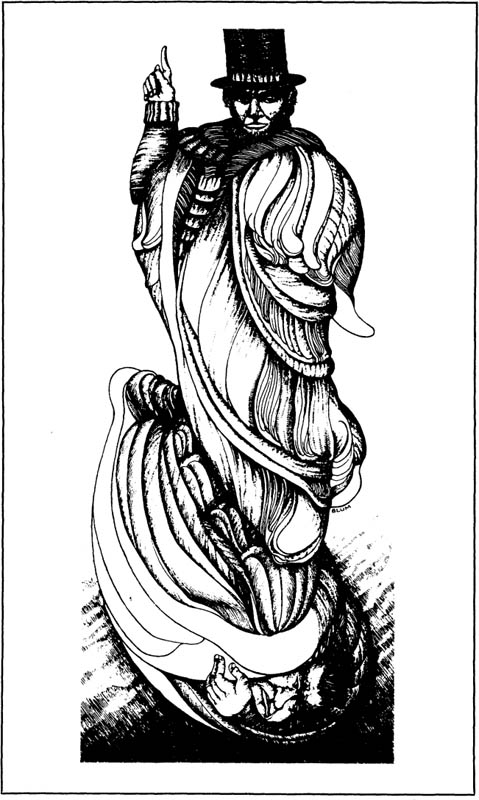

Illustrations by Zevi Blum

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To Cynthia, for everything (1987)

To Cynthia, for so much more than I ever imagined (2011)

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

The Constitution in American Civil Religion

CHAPTER TWO

The Moral Dimension of Constitutional Faith

CHAPTER THREE

Loyalty Oaths: The Creedal Affirmations of Constitutional Faith

CHAPTER FOUR

Constitutional Attachment: Identifying the Content of Ones Commitment

CHAPTER FIVE

The Law School, the Faith Community, and the Professing of Law

CHAPTER SIX

Conclusion: Adding Ones Signature to the Constitution

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

OVER THE MANY YEARS during which this book was gestating, one of the incentives for its completion was the opportunity I would then have to write an acknowledgments page that would convey my thanks for help to an ever-increasing number of friends and associates. Now the time has come, and I want to take full advantage of that opportunity. With completion has come as well chastening knowledge of the reality undergirding what had, as I read other writers acknowledgments, always seemed to me the cliche that those acknowledged were not responsible for any remaining weaknesses. Along with advice gratefully accepted there remain other suggestions that were unwisely rejected. (The problem, of course, is that I am not wise enough to know which of the rejected suggestions are in that category.) In any event, I am immensely grateful both for the opportunity to work with these many individuals and to the institutions that provided the setting for collaboration.

I begin with the institution that most directly contributed to my completing this work, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, which honored me with membership, half of which was funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, during 1986-87. The remaining funding came from the University Research Institute of the University of Texas. Without denigrating the importance of the funding, I want to register special gratitude for the almost literally incredible work environment provided at the Institute for Advanced Study; it made the writing of this manuscript a joy. In addition to the institution, I am grateful to several of its members, including Elizabeth Hill Boone, William Connolly, Clifford Geertz, Albert Hirschman, Joan Scott, and Barbara Herrnstein Smith, all of whom read drafts of chapters and discussed them with me. Encouraging words from Carl Schorske and Barbara and Dennis Tedlock early in the year were much appreciated.

One member of the Institute, Michael Walzer, deserves separate mention. He could be listed under almost all of the institutional references to follow: I first met him at Harvard; it was as a teaching fellow in his course at Harvard that I first became obsessed by the problem of pluralism, which in this book is the focus of Chapter Three. Equally important has been my participation with him in a continuing study group organized by the Shalom Hartman Institute on Jewish philosophy. I have never failed to benefit from his insights and ideas for the two decades I have been privileged to know him.

Having begun with my latest institutional debts, I now turn to my earliest one. Though it is now a full quarter-century since I arrived at Harvard as a graduate student in government, I remain under the influence of at least three individuals with whom it was my pleasure to study. Two, sadly, are now dead: Robert McCloskey and Louis Hartz. McCloskey provided an invaluable lesson in how to mix the study of constitutional law and more general American political and social thought. (He was also an extraordinarily decent man who contributed to my having an unusually happy experience as a graduate student.) Hartz provided a model of visionary thinking and absolute fearlessness in making comparisons and connections among thinkers and ideologies. Some worked, some did not, but there was never any doubt that one was stimulated by whatever he said. The third, happily, is still actively contributing to scholarship and intellectual life: Judith Shklar, too, has provided a model of absolute intellectual intensity and integrity that inspires even as it sometimes overwhelms.

After leaving Harvard, I was fortunate to receive a fellowship from the Russell Sage Foundation that allowed me to attend the Stanford Law School. The Law School provided me with both intellectual succor and good fellowship. It also provided me with the opportunity to deepen a personal and professional friendship with Paul Brest, whose traces run especially throughout Chapter One below.

My former colleagues at Princeton University, where I taught between 1975 and 1979, also left tracks that can be found in this book. In particular I wish to thank James Fleming, Amy Gutmann, Will Harris, Stanley Katz, Walter Murphy, Martin Sherwin, and Dennis Thompson. I also benefitted from the counsel of three new members of the Politics DepartmentJennifer Hochschild, Anne Norton, and Jeff Tuliswhom I got to know during my stay at the Institute.

Another Institute, far removed from the United States, must also be mentioned, for this book reflects in many ways my connection with the Shalom Hartman Institute for the Study of Jewish Philosophy, in Jerusalem, Israel. The director of the Institute, David Hartman, and its members all combine a blazing intellectual seriousness with personal decency and moral commitment. What relatively little I know about my own Jewish tradition I owe to the patience of my teachers at the Institute, including, in addition to the inimitable David Hartman, David Dishon, Moshe Halbertal, Menachem Lorberbaum, Zvi Marx, Noam Zion, and Noam and Zvi Zohar. It is also through the Institute and meetings in the United States, Canada, and Israel that I have gotten to know, and benefit from, Sidney Morgenbesser, Michael Sandel, and Alan Silver. The initial draft of Chapter Three was originally prepared for a conference on community membership that was held in Jerusalem in December 1985. One of the participants at that conference was the late Robert Cover, whose work is reflected at points in this book and whose passionate wisdom I, like so many others, will miss for the rest of my life.