WIDE

OPEN

TOWN

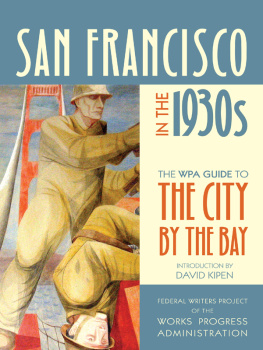

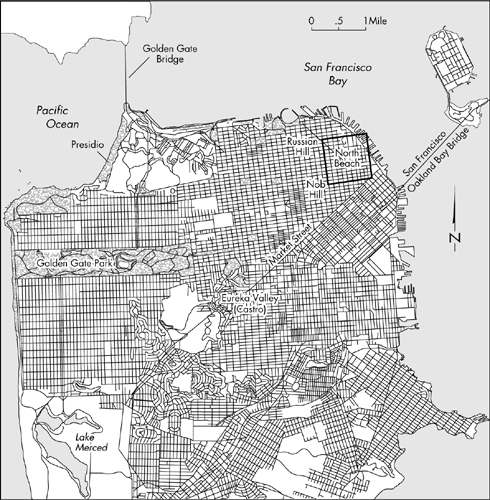

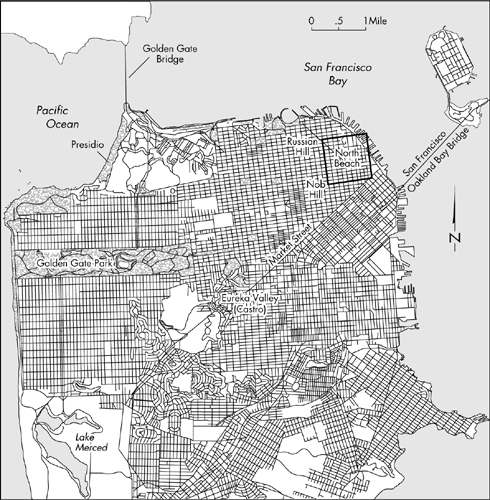

City of San Francisco, c. 1940.

WIDE

OPEN

TOWN

a history of

QUEER

SAN FRANCISCO

to 1965

nan alamilla boyd

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2003 by the Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Boyd, Nan Alamilla, 1963

Wide-open town : a history of queer San Francisco to 1965 / Nan Alamilla Boyd.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-520-20415-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. GaysCaliforniaSan FranciscoHistory.

I. Title.

HQ76.3.U52s2635 2003

305.906640979461dc21 2002151314

Manufactured in the United States of America

13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is both acid-free and totally chlorine-free (TCF). It meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

To Reba Hudson and Rikki Streicher

Contents

APPENDIX A

Map of North Beach Queer Bars and Restaurants, 19331965

APPENDIX B

List of Interviewees

Acknowledgments

This book is dedicated to Reba Hudson and Rikki Streicher. Lifelong friends, Reba and Rikki were part of a queer bar scene that flourished in San Franciscos North Beach district during the 1940s and 1950s. Through their stories as well as those of the forty others I interviewed for this book, San Franciscos queer history came vividly to life. The interviews unlocked what seemed to me to be a secret past, a history where gay men and lesbians socialized together in bars that were central to San Franciscos growing tourist economy. More importantly, through the assertion of the right to be different, they described a world that, in the end, became important to social change. I want to thank Reba, Rikki, and the others who agreed to let me interview them for this project. Their stories inspired me, and their histories frame this book.

This book began over ten years ago with the support of two key figures, Henry Abelove and Mari Jo Buhle, who encouraged me to develop a dissertation in U.S. lesbian and gay history. At the time, the infant field of queer studies was growing, and, in the tradition of womens history, community studies based on oral history research seemed an important first step in creating a discourse about lesbian and gay history. I also want to thank Anne Fausto-Sterling, Jacqueline Jones, and Robert Lee, who warmly guided me through graduate school and impressed me with their commitment to teaching. I also thank my graduate peers for their unswerving political commitments and general good sense: Gail Bederman, Laura Briggs, Oscar Campomanes, Peter Cohen, Krista Comer, Ann DuCille, Elizabeth Francis, Kevin Gaines, Jane Gerhard, Linda Grasso, Bill Hart, Matt Jacobson, Melani McAlister, Bob McMichael, Louise Newman, Donna Penn, Tricia Rose, Laura Santigian, Jessica Shubow, and Lauri Umansky.

In San Francisco, as I started my research, I attached myself to the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society of Northern California, where I found a vibrant research culture and a new academic home. Allan Brub encouraged me unfailingly. He taught me the basics of oral history research and inspired me with his friendship. Eric Garber, Paula Jabloner, Terence Kissack, Ruth Mahaney, Gayle Rubin, and Susan Stryker helped me in large and small ways, mostly through their dedication to local history. More than anyone else, though, I want to thank the indomitable Willie Walker. His quirky style and passion for San Franciscos queer history made every trip to the archives a pleasure.

Two grants, a Community Service Fellowship from Brown Universitys Center for Public Service and a pre-doctoral fellowship from the Womens Studies Department at the University of California at Santa Barbara, helped me through the difficult first years of research. Later, a job at the University of Colorado at Boulder brought me in contact with a new circle of scholars and friends. I want to thank my colleagues in the Womens Studies Program, Jo Belknap, Mary Churchill, Michiko Hase, Janet Jacobs, Alison Jaggar, Kamala Kempadoo, Susan Kent, Lisa Sun-Hee Park, Anne Marie Pois, and Marcia Westkott, who generously supported my work. The administrative staff in Womens Studies, Jeanie Lusby and Anna Vayr, aided my progress in uncountable ways. I also thank those at Boulder who have encouraged me with their friendship and support: Jo Arnold, Emilio Bejel, Irene Blair, Kathleen Chapman, Bud Coleman, Michael du Plessis, Maria Franquiz, Jane Garrity, Donna Goldstein, Julie Green, Karen Jacobs, Suzanne Juhasz, Patricia Limerick, Meg Moritz, Lisa Pealoza, Michelene Pesantubbee, Terry Rowden, Jan Whitt, Marcia Yanamoto, and Margie Zamudio.

At Boulder, I also had the support of students who shared my enthusiasm for queer studies: Jami Armstrong, Davida Bloom, Keri Brandt, Matt Brown, Deanne Buck, Jamie Coker, Carey Gagnon, Evalie Horner, Ben Humphreys, Carl Nash, Cathy Olson, Louisa Pacheco, Mary Romano, Elisabeth Sheff, Sarah Sturdy, Stacey Takaki, and Jill Williams. Tea de Silvestre and Robin Schepps helped transcribe some of my oral history tapes. Abby Coleman, Kris Gilmore, Evalie Horner, and Carl Nash also worked as research assistants in the final stages of completing the manuscript.

In 19951996, my research was supported by a Rockefeller Fellowship in the Humanities from CLAGS, the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the City University of New York Graduate Center. While I was in New York, my work benefited from the insights of Jeffrey Edwards, Jeffrey Escoffier, Elizabeth Freeman, Judith Halberstam, Jacob Hale, Henry Rubin, and Ben Singer, whose work in queer and transgender studies has had a great impact on my own. Finally, without the work of other queer historians, this book could not exist. I am deeply indebted to Allan Brub and John DEmilio for their early work on San Franciscos queer history. I am also indebted to the work of Brett Beemyn, Alex Chasin, George Chauncey, Martin Duberman, Lisa Duggan, Estelle Freedman, Katie Gilmartin, Ramn Gutierrez, John Howard, Miranda Joseph, Jonathan Ned Katz, Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy, Martin Meeker, Joanne Meyerowitz, Esther Newton, Will Roscoe, Leila Rupp, Siobhan Somerville, Marc Stein, and Jennifer Terry.

There were many research and reference librarians who helped me along the way. Paula Jabloner, an archivist at the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society, offered assistance at crucial moments. Susan Goldstein and Roberto Landazuri, at the San Francisco Archives of the San Francisco Public Library, helped me decipher the problem of police records and walked me through their labyrinthine clipping file collections. Keith Gresham helped secure important holdings in U.S. lesbian and gay history for the University of Colorado libraries. Reference librarians at the California State Archives provided access to the records of the California Alcoholic Beverage Control Board, and archivists at the Bancroft Library helped me locate the rare hotel magazines that ran advertisements for San Franciscos early queer establishments. I also thank Polly Thistlethwaite for her enthusiasm for this project and her countless hours of support, research- and otherwise.

Next page