The publisher gratefully acknowledges the

generous support of the General Endowment Fund of

the University of California Press Foundation.

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2011 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spooner, Mary Helen.

The general's slow retreat : Chile after Pinochet / Mary Helen Spooner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-25613-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-520-26680-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. ChilePolitics and government1988 2. Pinochet Ugarte, Augusto. 3. DemocratizationChile. I. Title.

JL 2631.S67 2011

Manufactured in the United States of America

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on 50# Enterprise, a 30% post consumer waste, recycled, de-inked fiber and processed chlorine free. It is acid-free, and meets all ANSI/NISO (z 39.48) requirements.

Once again, for Alan, Daniel, and Alexandra

Dictators ride to and fro upon tigers which they dare

not dismount. And the tigers are getting hungry.

Winston Churchill,

from a letter dated November 11, 1937

The spirit of democracy cannot be imposed from without.

It has to come from within.

Mohandas K. Gandhi,

statement to the press, September 17, 1934

I said to Felipe Gonzalez once, Imagine what it would be

like to be president of Spain with Franco still alive. I am

with my Franco. It's General Pinochet.

Patricio Aylwin,

president of Chile, 199094,

New York Times, April 30, 1992

Illustrations

Following .

Acknowledgments

Returning to Chile after so many years seemed a daunting task, and I am deeply grateful to Odette Magnet, whose encouragement, friendship, and extraordinary networking skills helped reconnect me with the country, and to my editor, Naomi Schneider, who gave me this opportunity. In addition to those interviewed for this book, I would like to thank Barbara Thompson for giving me a better understanding of banking practices and money laundering, as well as Juan Carlos Roman and Genaro Roman, Daesha Friedman, Judy Ress, and Francisca Donoso. Jimme Greco showed great patience with me while meticulously editing this book. My husband, Alan Stephens, supported me through this project, and our children, Daniel and Alexandra, are the most precious gift Chile gave us.

Introduction

The Chilean presidential palace, La Moneda, began life as a Spanish colonial mint in 1805, five years before the country was even a republic. During Chile's brutal 1973 coup, the palace survived a military bombardment, which destroyed the beams supporting the upper floors and reduced much of the Italian-designed edifice to a shell. For several years afterward La Moneda was boarded up, until General Augusto Pinochet, having won a dubious referendum extending his rule for another nine years, moved his headquarters into the palace in 1981.

La Moneda continued to project a grim image: the previous occupant, socialist president Salvador Allende, had committed suicide there during the coup, shooting himself after instructing his most loyal staffers to leave the building. His corpse was removed by soldiers and firefighters through a side door, which had been the private entrance for Chilean presidents. The military regime repaired much of the internal damage to the palace and added an underground bunker, where Pinochet conducted business. But the presidential side entrance remained blocked up with concrete, an architectural eyesore and sad reminder of the country's once-proud democratic tradition.

Chile returned to democracy in 1990, and today entire sections of La Moneda are open to the public. The palace's exterior has been brightened, with the once-grayish outer walls now painted white. A replica of the original carved pine door has been installed in the restored presidential side entrance. Casual visitors may walk up to the main entrance of the palace and, after submitting to a brief security check, wander through two exquisite courtyards filled with fruit trees and outdoor sculptures.

La Moneda also hosts concerts and guided tours, and the former dictator's bunker has been transformed into a new museum and cultural center, which opened in January 2006. But shortly after the cultural center was inaugurated, a controversy erupted over souvenirs sold in the gift shop. A series of postcards, Presidentes 19702010, included the ill-fated Salvador Allende, three civilian presidents who served after military rule ended, and the newly elected Michelle Bachelet, Chile's first female president. Conspicuous by his absence was Pinochet, and when some visitors to La Moneda complained, sale of the postcards was quickly suspended.

Chilean officials offered mixed explanations: some said that the postcards were the work of a private company offering what it thought visitors would buy, while others explained that the postcard series was limited to democratically elected presidents. The culture minister suggested that it might be more appropriate to have a set of postcards featuring all heads of state dating from the nineteenth century. It was a mistake to exclude Pinochet, he said, for Pinochet had been president of Chile for seventeen years, whether we like it or not.

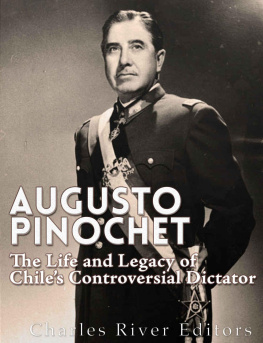

Had it been up to Pinochet and his most determined supporters, his regime would have lasted a quarter of a century. The one-man presidential plebiscite on October 5, 1988, to extend his rule for another eight years was one he fully expected to win. His defeat at the polls paved the way to free elections and Chile's readmission into an international community that had held the country at arm's length during the military regime. But Pinochet continued to cast a long and intimidating shadow as army commander until 1998, and he had begun an indefinite term as senator for life when his arrest in London shattered his indestructible image.

He returned to Chile a weakened figure, or as one congressman put it, politically dead. And yet he still managed to dodge a series of judicial investigations into some of the worst crimes of his regime as well as an inquiry into an illicit fortune he had built up during his rule and hidden in bank accounts abroad. Pinochet may have left office, but the remnants of his power and his authoritarian legacy would take decades to dismantle.

Now that he is gone, I feel I can finally write my memoir, a former cabinet minister who had worked with Pinochet as army commander told me. He shook his head, as if to convince himself that the coast was finally clear. But the Pinochet legacy was still not dismantled, and the former official had reason to be cautious: had he published his book a few years earlier, he might have faced prosecution under state security laws leftover from the regime. Not only had there been no immediate repeal of such laws when Pinochet left the presidency, but some politicians in Chile's emerging democracy would find them useful for their own ends. Dictatorship would not disappear overnight.