Table of Contents

To Pamela

PREFACE

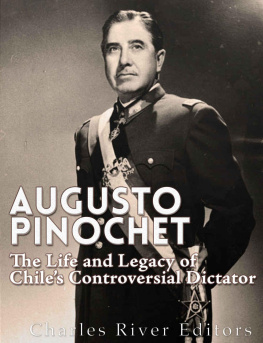

GENERAL AUGUSTO PINOCHET IS ONE of the worlds most recognizable Latin American political figures. Whether Chileans like it or not, the name of their former dictator is remembered from Asia and Africa to the Americas and Europe, by taxi drivers, ambassadors, salesmen, and presidents. Pinochet is in a class with Francisco Franco, Joseph Stalin, Ferdinand Marcos, and the Shah of Iran.

The dictators name did not recede into obscurity with his death in December 2006. In October 2007, about a hundred students who staged a demonstration at Tehran University against President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, demanding the release of detained fellow students, chanted, Ahmadinejad is Pinochet. Iran will not become Chile! When the former chess champion Gary Kasparov competed in the 2008 Russian presidential elections, he accused Vladimir Putin of being Russias Pinochet and sought advice from former Chilean dissidents. The former dictator of Chad, Hissene Habr, was widely known as the African Pinochet.

Many of todays world leaders were inspired to enter politics precisely in order to rally to the cause of Chilean democracy. Chiles struggle against Pinochet became an international cause clbre. Todays global human rights movement emerged from the worldwide protests and denunciations of the Pinochet dictatorship, spearheaded by Amnesty International and numerous other human rights NGOs.

Pinochets overthrow of Socialist president Salvador Allende in 1973 led Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev to reverse a long-standing policy and endorse the principle of armed struggle in third world countries. The lesson of Pinochets violent coup and the subsequent loss of Communist Party clout in Chile was so important to Moscow that Soviet fear of another Chile triggered the USSRs invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, to prop up the Communist regime in Kabul.

The former dictators arrest in London in 1998, following a warrant issued by a Spanish judge, announced a major change in the administration of international law regarding former heads of government. Henceforth, no former tyrant could be sure of escaping the global justice system.

Yet there is little agreement on Pinochet and his legacy. Margaret Thatcher saw Pinochet as a bulwark against Communism and a leader in privatization of state enterprises, and actively demanded his release. Chile served as a successful laboratory for the Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman and his monetarist theories, which were pursued by Chilean economists trained at the University of Chicago. Pinochets Chile would later become the good International Monetary Fund student, the inspiration for the Washington Consensus, a set of guidelines that showed the road that countries had to follow to put their economic houses in order as the IMF wished, and to grow. President George W. Bushs intended reform of the Social Security system drew its inspiration from the pension system imposed by Pinochet in 1980 and later imitated in many countries.

In the 1970s, Pinochets Chile was the focus of an unprecedented congressional debate on U.S. covert action and human rights policy. Those hearings marked the beginning of Congresss challenge to the executive branch on the conduct of foreign policy. Richard Helms was the first CIA director ever to be indicted, for failing to answer questions before the Senate on the Chilean investigation. The names of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger became inextricably linked to Pinochet and Chile. Both dedicated extraordinary time and resources to removing what they perceived as a red threat in the Americas and enthusiastically backed Pinochet.

The purpose of this book is to explore Pinochets impact on contemporary history, and the various meanings and symbols that his figure evokes. This is not a biography but an examination of Pinochets times and legacy. In a sense, it is my political memoir of Pinochet and his times. Because of him, the course of many of our lives was changed and our earlier plans became subordinated to the priority of fighting the dictatorship. In addition to my own experiences, I have used abundant interviews with pivotal players, confidential documentation, and the vast journalistic coverage of the Pinochet period to narrate events and details of many episodes currently unknown to the general public.

Pinochet did not quite match the caricature of Latin American dictators we see portrayed in American movies or in Gabriel Garca Mrquezs great novel The Autumn of the Patriarch. To be sure, he was no Bismarckbut neither was he just another Somoza. He was a man of limited intellect who, placed at a historic crossroad, nonetheless led a process of change in Chile that had a powerful international impact.

Most Latin American dictators ran disastrous economies. Pinochets was the exception. At first, he leaned toward nationalistic economic policies. It was Admiral Jos Toribio Merino who pressured him into accepting a new economic model, just as he had once pressured him to join the military coup in the first place. Merino was the true leader of the coup and the leader of the virtual economic coup. But just as on September 11, 1973, when Pinochet had no choice but to follow although he assumed full control once on board, he accepted the Chicago Boys economic plan and gradually became a true believer in the scheme. Without that revolutionary economic model, Pinochet would be a minor chapter in the history of Latin American military dictators.

As a result of his economic record, though for many the man is the emblem of twentieth-century cruelty, others see Pinochet as the leader who, despite his tyrannical rule, guided the nation to economic recovery and laid the foundation for growth and modernization. The agonizing question is: Was Pinochet necessary? Could Chile have reached its present prosperity without him? This book will address such questions.

Pinochets ideology was self-interest. In times of passionate commitments and causes, his policy was realpolitik: be pragmatic, appear neutral, and cultivate the trust of those with power and authority. A military man who remained on active duty longer than any other soldier in the world, Pinochet was, above all else, a survivor. For all his ethical and intellectual shortcomings, he possessed a remarkable instinct for power. General Pinochet wasnt an absolute dictator, though he wanted to be one; he accumulated enormous power but recognized its limitations. He knew how to exercise authority and was smart enough to rely on close advisers, whom he generally chose quite well. He was not intelligentbut he was astute. He did not get where he did by a carefully planned design, but rather by taking advantage of favorable circumstances, former president Patricio Aylwin told me.

Ultimately, Pinochet was the accidental product of a polarization the world experienced in the late sixties and early seventies following the intensification of U.S. anti-Communist policies in response to the Cuban revolution, the national security doctrines espoused by South American military regimes, the 1968 riots in Paris and the extinguished Prague Spring, the Vietnam War, the antiwar protests and the civil rights movement in the United States, Ch Guevaras guerrilla movement in Bolivia, the massacre of students in Tlatelolco Plaza in Mexico City, and even the strongly anticapitalist message of the Vatican. That international reality was mirrored in Chile: homegrown tensions deepened as the Socialist-led left began to advocate revolutionary change, the right defended the status quo with increasing fierceness, and the center, instead of playing a pragmatic role, was caught up in the polarizing tendencies in the country. Hence, political parties were unable to form majority-rule coalitions, and political consensus broke down.