Table of Contents

Guide

Pages

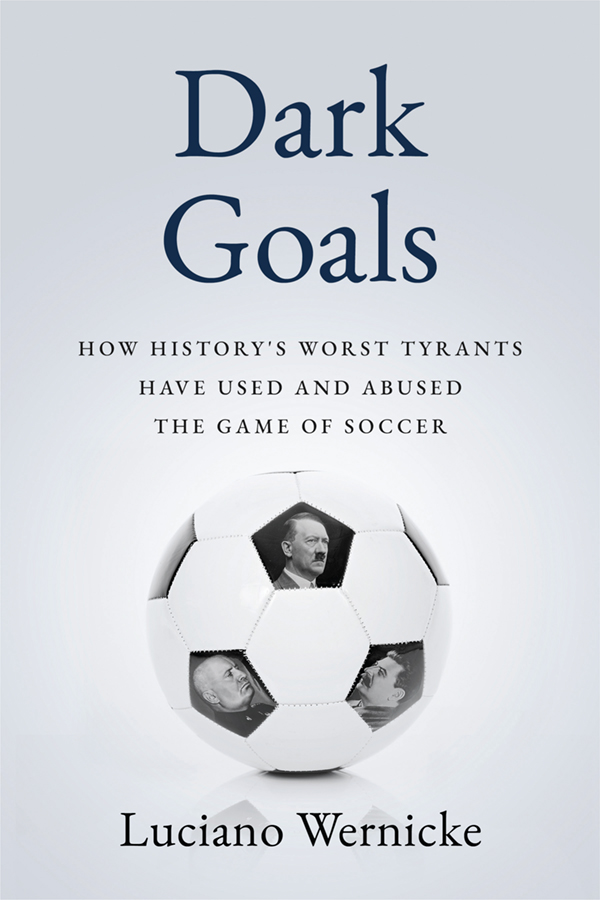

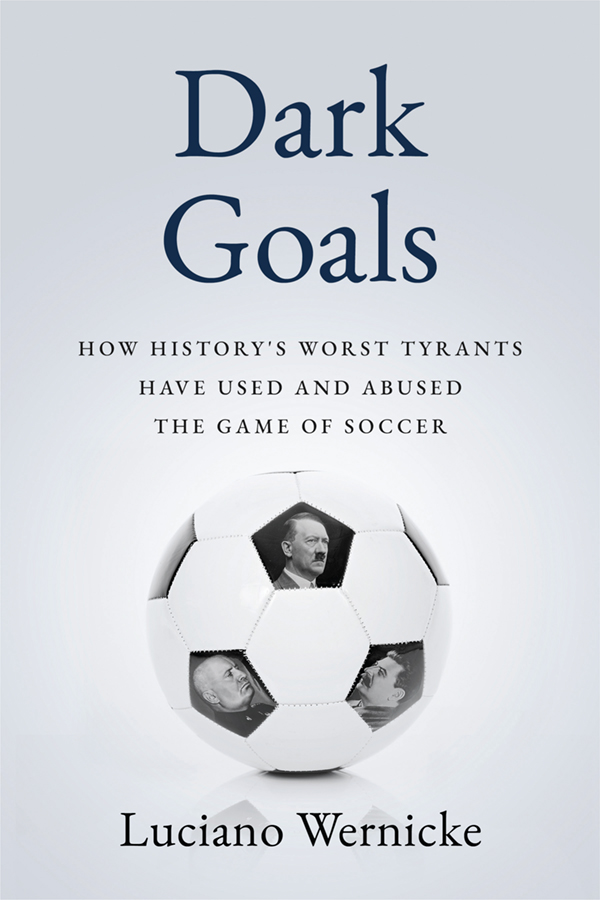

DARK GOALS

How Historys Worst Tyrants have Used and Abused the Game of Soccer

LUCIANO WERNICKE

Sutherland House

416 Moore Ave., Suite 205

Toronto, ON M4G 1C9

Copyright 2022 by Luciano Wernicke

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information on rights and permissions or to request a special discount for bulk purchases, please contact Sutherland House at

Sutherland House and logo are registered trademarks of The Sutherland House Inc.

First edition, October 2022

If you are interested in inviting one of our authors to a live event or media appearance, please contact for more information about our authors and their schedules.

We acknowledge the support of the Government of Canada.

Manufactured in China

Cover designed by Lena Yang

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Dark goals : how historys worst tyrants have used and abused the game of soccer / Luciano Wernicke.

Names: Wernicke, Luciano, 1969- author.

Description: Includes index.

Identifiers: Canadiana 2022025060X | ISBN 9781989555842 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: SoccerPolitical aspectsHistory20th century. | LCSH: SoccerSocial aspectsHistory20th century. | LCSH: SoccerHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC GV943.9.P65 W47 2022 | DDC 796.334dc23

ISBN 978-1-989555-84-2

eBook ISBN 978-1-989555-92-7

For Don Pedro Juan Urreta.

For the people, winning a soccer game is more important than capturing a city in the East.Joseph Goebbels

Soccer is not a simple game. It is a weapon of the Revolution.Ernesto Che Guevara

Those who believe that sport has nothing to do with politics, either dont know anything about sport or dont know politics.Gerardo Caetano

Preface

THREE-TIME WORLD CHAMPION PEL, dressed in an impeccable light-grey, double-breasted suit, did some juggling with the ball before passing it with legendary grace to the visitor. The ball bounced before him on the artificial grass and was suspended for a moment, as if hanging by a threada perfect set up. The president of the United States took careful aim and extended his long right leg, but his foot, encased in a brown dress shoe, missed the target. Bound by Newtons law, the ball collided with Bill Clintons knee and went astray while the crowd surrounding the little field of the Mangueira favela, one of Rio de Janeiros most emblematic football pitches, murmured its disapproval.

Pel, suppressing any temptation to mock the visitor, kept his pearly smile frozen. He was not there in his official position as Extraordinary Minister of Sport for the thenBrazilian ruler Fernando Henrique Cardoso, but as an expert in public relations. He took another ball and tried again. This time it went better. Just a little. The American presidents left foot managed to at least touch the ball before it again caromed off his knee.

On the verge of resignation, Pel went to Plan B and placed a third ball on the synthetic green carpet a few metres from the goal, where it sat perfectly still. The master of ceremonies chose a token teenager for goalkeeper to try to stop a Clinton penalty kick. The emboldened president gauged the distance to the motionless keeper, took two steps, and booted without technique or elegance. This time the ball rolled where intended, kissing the left post. The goaltender flew to opposite post as the script ordered. Goal! The audience erupted in celebration, a roar that Nero would have envied, and the curtain went down with the desired happy ending.

Why did the most powerful representative of the most powerful country on the planet agree to make a fool of himself in one of the poorest neighbourhoods in South America, in front of thousands of witnesses, in front of a hundred television cameras? What led a man of surpassing political influence, who had never excelled on the sports field, never even seen a soccer ball in his native Arkansas, to star in a crude parody of soccer mere steps from the Maracan, one of the great soccer temples of the world?

The answer is simple: politics. In October 1997 Clinton visited South Americas three economic giants, Venezuela, Argentina, and Brazil, to invite them to join the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) pact proposed three years earlier in Miami, during the First Summit of the Americas. Armed with his renowned capacity for seduction, the American president was prepared for anything, for any sacrifice. On Brazilian soil, it is accepted that soccer is the universal creed. That is why Clinton assumed his duty and took to the field of play. With that gesture he needed no words to spread his message: I come from a country that many hate, where another language is spoken, where other sports and games are preferred, but look, I play soccer, I am like you, I am a good guy. We can be friends. Clintons score with Pel got the FTAA game off to a fine start. Unfortunately for him, the game would be finished by a different player: George W. Bush would preside over a massive change in momentum and lose the FTAA contest by a landslide.

The Clinton manoeuvre is one small example of the influence that flows from a simple ball. Since soccer became a sport after the drafting of its first official regulation in 1863 in a London tavern, the leather ball has bounced to all corners of the planet. First aboard the ships of Great Britain (both merchant and military), then by train and wagon from ports to the most remote locations. By the beginning of the twentieth century, soccer had seized the world. Not only was it the most popular sport, with its simple rules, its universal accessibility, its symbols and rituals, but in a more fundamental way it was both the only true universal language, according to the French ethnologist Christian Bromberger, and, for the Spanish writer Manuel Vzquez Montalbn, the most widespread religion on the planet.

Political and social leaders, those legitimized both by popular will and by force, discovered in soccer a convenient ally. It was a means to shorten the distance between themselves and the people. It was a subtle way to expose the virtue of the individual hero and, at the same time, reinforce the value of collective effort. It was a tool to stimulate local, regional, or national belonging, strengthen identity, indoctrinate, exacerbate patriotism or xenophobia (or both). It was a metaphor demonstrating that triumph is a deserved reward while defeat is the fruit of injustice or foreign conspiracy.

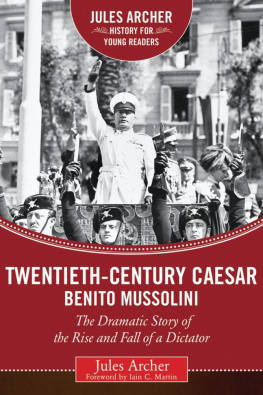

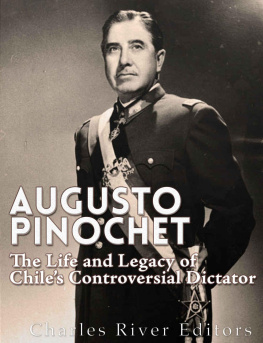

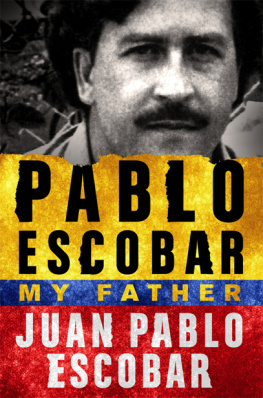

Personalities such as Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, Evita and Juan Pern, Augusto Pinochet, and Pablo Escobar, some of the principal movers of twentieth-century history, found in soccer a magnificent partner for the manipulation of the masses, prolonging their stay in power, justifying aberrant acts, outdoing an enemy, or simply recreating the Roman bread and circuses (in many cases without bread), although some of them, as will be seen in this book, detested soccer as a sport.

The recipe of these despots was to transform the beautiful game into the useful game, dying the ball the appropriate colours and rolling it towards the appropriate goal. Many of these tyrants benefitted from their association with the game, but only temporarily. All would eventually fail, and for the same reasons. They had ignored three fundamental truths of soccer: one, you must have a good aim; two, sometimes the ball bounces where it wants; three, all games come to an end.

Next page