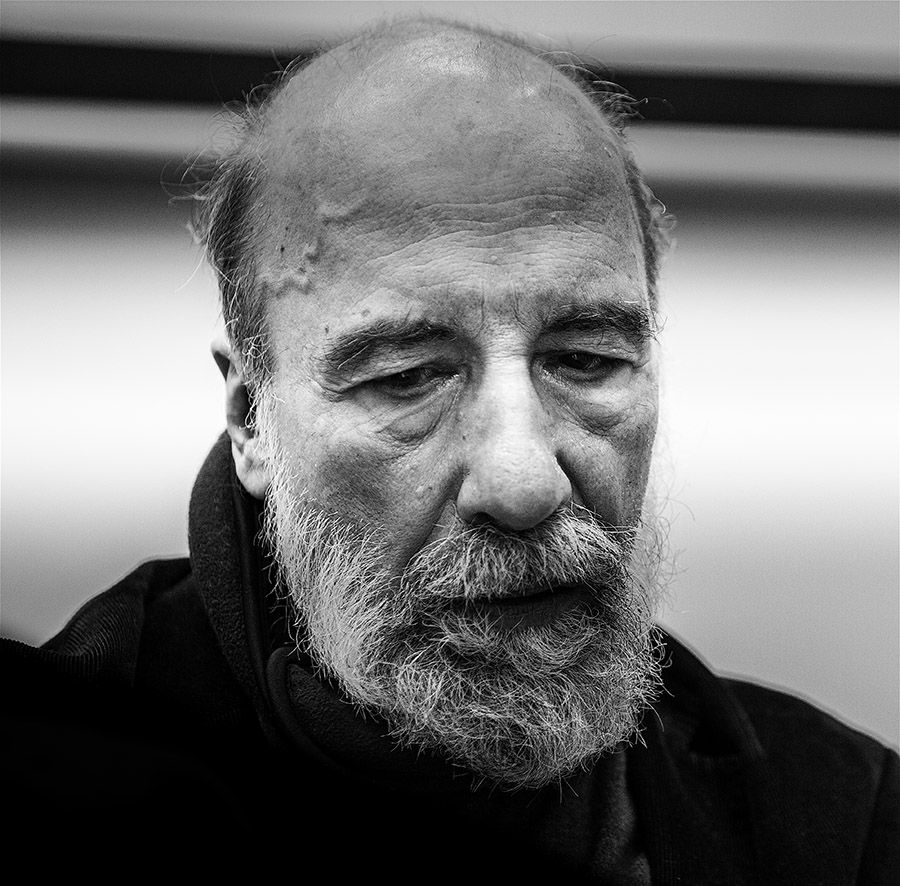

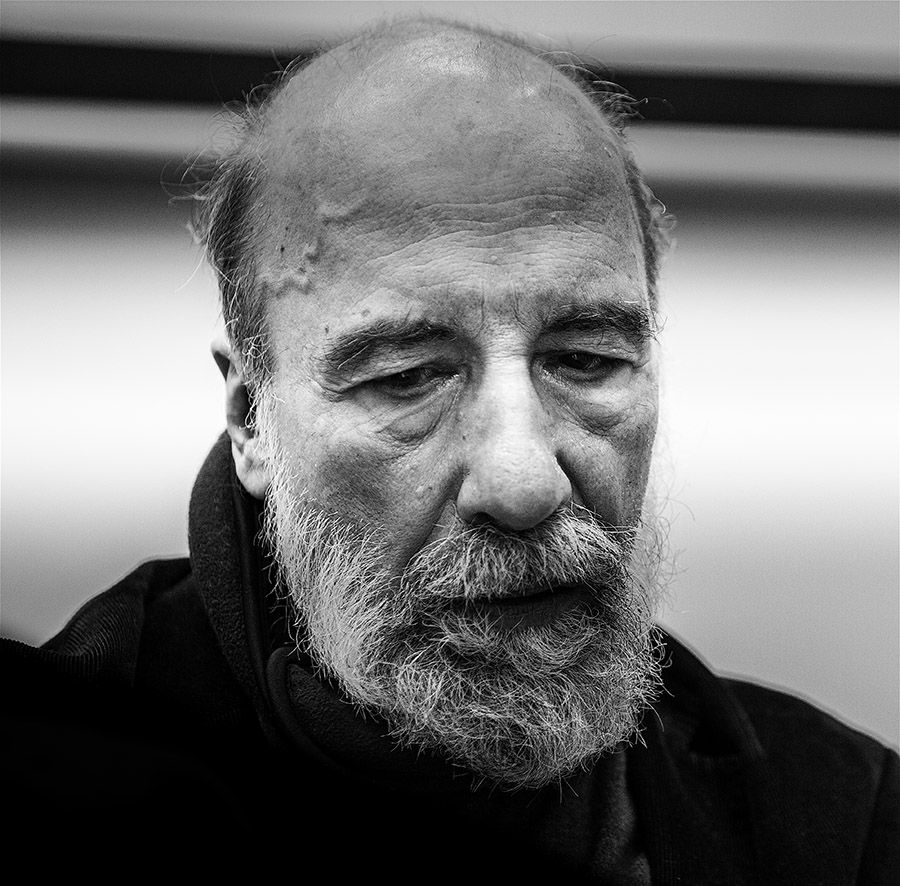

Photograph by Pepe Torres R AL Z URITA (b. 1950) was born in Santiago de Chile. In 1973 he was arrested by the Pinochet regime and imprisoned in the hold of a ship. He was a founder of the group Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA), which undertook extremely risky public-art actions against the regime. In 1982 five airplanes wrote his poem La Vida Nueva in the sky above New York City, and in 1993 he had the phrase NEITHER PAIN NOR FEAR bulldozed into the Atacama Desert in a permanent, two-mile-long installation, visible only from above. Zurita received the Chilean National Prize for Literature in 2000 and the Asan Memorial World Poetry Prize in 2018.

W ILLIAM R OWE s Collected Poems were published in 2016 by Crater Press. He has translated a number of Latin American poets, including Rodolfo Hinostroza, Juan L. Ortiz, Hugo Gola, Magdalena Chocano, Nstor Perlongher, and Mario Montalbetti. Three Lyric Poets, his study of Lee Harwood, Chris Torrance, and Barry MacSweeney, was published in 2009. N ORMA C OLE is a poet, painter, and translator. Her most recent books of poetry include Fate News, Actualities, Where Shadows Will, and Win These Posters and Other Unrelated Prizes Inside.

Her translations from French include Danielle Colloberts It Then, the anthology Crosscut Universe: Writing on Writing from France, and Jean Daives White Decimal. Cole lives and works in San Francisco. Ral

Zurita INRI TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH BY WILLIAM ROWE

PREFACE BY NORMA COLE

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2003, 2009 by Ral Zurita Translation copyright 2009, 2018 by William Rowe Preface copyright 2018 by Norma Cole All rights reserved. Cover design by Emily Singer Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zurita, Ral author. | Rowe, William, translator. | Cole, Norma, author of introduction.

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2003, 2009 by Ral Zurita Translation copyright 2009, 2018 by William Rowe Preface copyright 2018 by Norma Cole All rights reserved. Cover design by Emily Singer Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zurita, Ral author. | Rowe, William, translator. | Cole, Norma, author of introduction.

Title: Inri / by Ral Zurita ; translated by William Rowe ; introduction by Norma Cole. Other titles: Inri. English Description: New York : New York Review Books, 2018. | Series: New York Review Books poets Identifiers: LCCN 2018024724| ISBN 9781681372785 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681372792 (epub) Classification: LCC PQ8098.36.U75 I5713 2018 | DDC 861/.64dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018024724 ISBN 978-1-68137-279-2 v1.0 For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Contents

INRI

PREFACE

S EA OF PAIN is an invitation from Ral Zurita. In 2016 at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in Kerala, India, in a dilapidated colonial warehouse, Zurita created an installation of seawater and poetry, and dedicated it to Galip Kurdi, the brother of Aylan Kurdi.

Fleeing Syria, both children drowned in the Mediterranean on September 2, 2015, and Galips body was never found. The iconic photograph of Aylan, whose body washed up on the sand near Bodrum, Turkey, as though in a childrens graveyard, was taken by the Turkish photographer Nilfer Demir. There are no photographs of Galip Kurdi, he cant hear, he cant see, he cant feel. He is a representative of the other faceless forgotten in other crises and conflicts around the world, the poet says. I am not his father, but Galip Kurdi is my son. As you walk through knee-deep seawater, you read the poem written on canvases on the walls: In the Sea of Pain Dont you listen? Dont you look? Dont you hear me? Dont you see me? Dont you feel me? In the sea of pain Wont you come back, never again, in the sea of pain? If water has memory, it will also remember this, says Ral Zurita in The Pearl Button, a film by Patricio Guzmn.

About this installation, Zurita says, Its hope for the world, which has no hope. Possibility for the world that has no possibility. Its love for the world that has no love. Its the experience of love that infuses INRI. Experience, from the Latin experire, means to undergo, endure, suffer. To feel, from the Latin noun periculum, which means danger, risk.

What is at stake here? On the morning of September 11, 1973, the armed forces of Chile staged a coup. While the Palacio de La Moneda was being attacked, President Salvador Allende died and soon after General Augusto Pinochet established a military dictatorship. In Valparaso, where he had been an engineering student, Zurita and thousands of others were rounded up and herded into the National Stadium. Zurita, along with around eight hundred others, were then packed into the hold of a ship and tortured. Some, like Zurita, were eventually let go. During those years, thousands of people disappeared.

The authorities would not tell what had happened to them. Zurita chose to stay in Chile, enduring the brutal seventeen-year dictatorship when he could have gone into exile like so many others who feared for their lives. There is power and agency in staying in a dangerous place when one has the choice to leave. I had to learn how to speak again from total wreckage, almost from madness, so that I could still say something to someone, Zurita writes in a note about INRI, at once making clear the immediate context for its composition. On January 8, 2001, in a nationally televised speech, social-democratic President Ricardo Lagos announced, with brevity, information pertaining to those who were still unaccounted for in the government-sponsored killings during the 1970s. These missing people had been kidnapped by the security forces and tortured, their eyes gouged out, and their bodies thrown from helicopters into the ocean, the lakes, and the rivers of Chile.

And the Atacama Desert in the north. People knew about it, but there was no corroboration. Then suddenly there was. Looking for the disappeared was a thorn in the countrys soul. After this announcement, Viviana Daz, the president of the Association of Families of the Detained and Disappeared, said, Ive spent my whole life looking for my father. Now I know Ill never find him....

To discover that he is in the depths of the ocean is terrible and distressing. Even though, as Zurita says, they knew what had happened, the actual acknowledgment, the validation, came as a shock and a rupture in time. Reports and evidence of committed poured forth. Not needing to prove the facts anymore, what does the tragedy mean? How do you carry on? How do you hold the remembering, the identification, the trauma that took place, is still taking place, taking space to represent a memory? As Emmanuel Lvinas wrote in Existence and Existents, Being remains, like a field of forces. From the horror that was and still is, Zurita embraces the disappeared, loving and naming them again and again, stopping the wounds with his fingers, touching and giving us raised dots of braille letters with the particularity of fingertips, accustomed always to follow yours. In On Collective Memory, Maurice Halbwachs observes, While the collective memory endures and draws strength from its base in a coherent body of people, it is individuals as group members who remember.

Photograph by Pepe Torres R AL Z URITA (b. 1950) was born in Santiago de Chile. In 1973 he was arrested by the Pinochet regime and imprisoned in the hold of a ship. He was a founder of the group Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA), which undertook extremely risky public-art actions against the regime. In 1982 five airplanes wrote his poem La Vida Nueva in the sky above New York City, and in 1993 he had the phrase NEITHER PAIN NOR FEAR bulldozed into the Atacama Desert in a permanent, two-mile-long installation, visible only from above. Zurita received the Chilean National Prize for Literature in 2000 and the Asan Memorial World Poetry Prize in 2018.

Photograph by Pepe Torres R AL Z URITA (b. 1950) was born in Santiago de Chile. In 1973 he was arrested by the Pinochet regime and imprisoned in the hold of a ship. He was a founder of the group Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA), which undertook extremely risky public-art actions against the regime. In 1982 five airplanes wrote his poem La Vida Nueva in the sky above New York City, and in 1993 he had the phrase NEITHER PAIN NOR FEAR bulldozed into the Atacama Desert in a permanent, two-mile-long installation, visible only from above. Zurita received the Chilean National Prize for Literature in 2000 and the Asan Memorial World Poetry Prize in 2018.

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2003, 2009 by Ral Zurita Translation copyright 2009, 2018 by William Rowe Preface copyright 2018 by Norma Cole All rights reserved. Cover design by Emily Singer Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zurita, Ral author. | Rowe, William, translator. | Cole, Norma, author of introduction.

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2003, 2009 by Ral Zurita Translation copyright 2009, 2018 by William Rowe Preface copyright 2018 by Norma Cole All rights reserved. Cover design by Emily Singer Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zurita, Ral author. | Rowe, William, translator. | Cole, Norma, author of introduction.