Table of Contents

Guide

More Advance Praise for American Apartheid

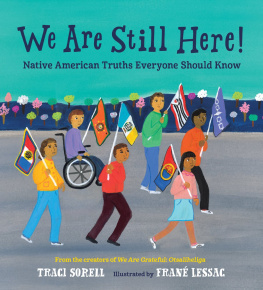

American Apartheid should be required reading for anyone concerned with equality and justice in America. The book is a comprehensive, understandable and shocking insight into the oppression that we Native Americans are still dealing with in the twenty-first century.

Michaelynn Hawk, Crow Tribe; Director/organizer of Indian Peoples Action and Jeannette Rankin Award recipient

I am so happy to see tribal youthand the cultural continuity they representincluded in American Apartheids beautiful photographs and thoughtful, informative text. In addition to the difficult issues we face, which are detailed conclusively here, readers will see what is good and true and eternally meaningful about our communities.

Julie Garreau, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe; Executive Director of the Cheyenne River Youth Project

American Apartheid paints a picture of the daily life of Native people that is full of hope. It reminds us, as American Indians, that understanding how to walk in the present requires knowing how and why our ancestors created the path we are onand that we have a collective responsibility for the wellbeing of our descendants. The stories in this book reflect the relationality, continuity and reciprocity that have always been at the center of social change in Indian country. We will always find a path to revive and survive as nations and cultures.

Judith LeBlanc, Caddo; Director, Native Organizers Alliance

Two topics foreign to the mainstream media are immediately noticeable in Stephanie Woodards book, American Apartheid: voter suppression and gerrymandering of Indian reservationstwo issues that must be addressed in order to have self-determination and inclusion in Indian country.

Tim Giago, Oglala Lakota, Harvard Neiman fellow, editor of Native Sun News Today, founder of Indian Country Today

In this book, Stephanie Woodard continues her commitment to amplifying Native American voices, highlighting stories of struggle but also of hard-earned progress toward self-determination. Throughout my life in Alaska, I have learned that when people are free to control their own lands and resources, they control their futures.

US Senator Mark Begich

I spent my career in political life, which included nearly two decades as a Senator from South Dakota, in service to my states citizens, including its Native people. This important book shows us how resilient Native Americans have been and how much adversity they have faced, and are still facing, in working on behalf of their land and people.

US Senator Tim Johnson

This book is a magnificent culmination of Stephanie Woodards work reporting on people who know what really matters.

Christopher Napolitano, Creative Director, Indian Country Media Network, 20112017

In American Apartheid, Stephanie Woodard captures the true spirit and determination of Native Americans who rise above discrimination and take actions that improve the conditions of their people. Reading it gives me hope that the continued efforts of Native Americans will one day mean an end to the American apartheid.

Bruce A. Finzen, attorney, Robins Kaplan LLP

Stephanie Woodards deep respect, keen observations and analysis in American Apartheid represent a fresh approach to urgent contemporary issues confronting tribal governments and American Indian people. The American Indian voices resonate with resilience, outrage and optimism for their childrens lives. Listening could improve all of our lives.

Marti L. Chaatsmith, Comanche/Choctaw; interim director, Newark Earthworks Center

Copyright 2018 by Stephanie Woodard.

All rights reserved.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the publisher. Please direct inquiries to:

Ig Publishing

Box 2547

New York, NY 10163

www.igpub.com

ISBN: 978-1-632460-69-1 (ebook)

Cover photographs, left to right, top to bottom: Navajo permaculture teacher Justin Willie; dreamcatcher by Izzie Zephier, Ihanktonwan Dakota; Crow Creek Sioux reservation (Stephanie Woodard). Puyallup tribal members; Zuni Pueblo dance group Anshe:kwe; Joseph Holley and his grandson (both Western Shoshone) collecting sweat-lodge rocks (Joseph Zummo).

CONTENTS

In northern Nevada, a community map welcomes visitors to the Battle Mountain Band of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone Indians and guides them to its library, its environmental department, and other tribal offices. (Joseph Zummo)

A DERELICT SALOON WITH AN ATTACHED JAIL sits just north of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, on the deserted main drag of a blink-and-youll-miss-it South Dakota town. The wooden exterior is weathered in streaks of black and gray, and the front door is boarded up. Crumbling longhorn skulls hang from a faded sign proclaiming that the bar was built in 1906. It also read No Indians Allowed until, at some point, the word No was mostly painted over. The lockup is a rusted open-air cage with doors that creak when pulled open. No one drinks here anymore, but it is easy to find booze nearby. Road signs along area highways direct travelers, including those from Pine Ridge, which has long banned alcohol, to bars and stores selling liquor. A field is planted with signs that tilt this way and that as they compete for customers: Horseshoe Bar, 3 Blocks Wagon Wheel Bar, 2 Blocks Bud Light, and more. In the midst of them, another tilted sign touts a church, seemingly as an antidote for the alcohol.

The tumbledown saloon and sagging signs deliver a message that applies far beyond this remote corner of the plains. Native people are not welcomeor maybe they are, to one kind of establishment that offers oblivion and another that extends an alien religion as a way to fend it off. Both institutions are predators of a sort, pushing and pulling at Native communities in a pattern I have seen in various guises during nearly twenty years of involvement with Indian-country stories, first as an editor and then, since 2000, as a reporter. In one story after another, I observed that tribal communities are set apart from the rest of us geographically, socially, politically, and economically. These include both Indian reservations and the urban Indian neighborhoods to which tribal members moved or were relocated in past decades by the federal government. Indigenous people are isolated in an archipelago of deeply impoverished islands in the vast sea of American wealth. At the same time, tribal members seek to participateamong many ways, they serve in the US armed forces in a greater proportion than any other group, they have been fighting for equal voting rights and the chance to participate fully in our democracy for almost a century, and they have a sense of responsibility to the earth and all its inhabitants that informs their lives.

The word apartheid was first used to describe South African policies that segregated and discriminated against that countrys original inhabitants. It has come to mean more generally any system that works that way. As time went on and I reported stories in various subject areaschild welfare, sacred sites, health, and othersI acquired ever more detail about the ways in which the word is an apt description of the relationship between the United States and its first peoples. In 2016, the economic strictures placed on Indian country came into sharp focus for me while I was covering a Navajo familys struggle to obtain a reasonable payment in return for renewing the right of way for an oil pipeline crossing its homesite. In looking at how the federal government had arranged for an oil company to offer a pittance for access to the familys land, I learned about the systemic nature of tribal members economic isolation. It is no mistake that many reservations are poverty-stricken, while money pours through them to a surrounding ring of dusty, angry border towns that are resentful of their dependence on a reservation. Paternalistic federal policies target Native people with heavy-handed precision. The United States controls a remarkable range of contemporary Native life, but not necessarily for Natives benefit. If a tribe wants to build a housing development or protect a sacred site, if a tribal member wants to start a business or plant a field, a federal agency can modify or scuttle the plans. Conversely, if a corporation or other outside interest covets reservation land or resources, the federal government becomes an obsequious bondservant, helping the non-Native entity get what it wants at bargain-basement prices.

Next page