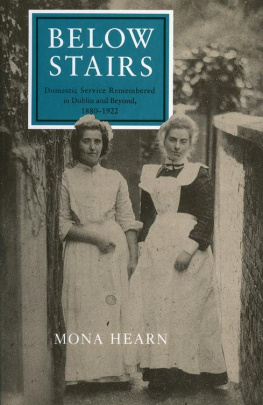

One hundred years ago domestic servants were a familiar part of everyday life in Ireland; today they have virtually disappeared. The prospect of managing without a servant was unthinkable to middle-class householders in the early 1900s. Yet, within a couple of generations, that change occurred, and had a profound effect on the social life of the country. Now the domestic servant is but a fading memory to the older generations.

In the last century and the early years of this century most young girls, and some boys, from the lower social classes went straight from school to service, sometimes the very next day. They joined the ranks of what was by far the single largest occupational group for women; in 1881 48 per cent of employed women in Ireland were in the domestic class. There was a steady decrease in the number of domestic servants from then on, but domestic service was only surpassed by manufacturing industry in 1911. It was still the second largest employer of women with 125,783 female indoor servants. Indeed any account of the employment of women in the nineteenth or early twentieth centuries must afford a prominent place to domestic service.

The importance of domestic service as an occupation which not only affected the whole life of those engaged in it but also impinged , in an intimate and special way, on the lives of those employing servants, has never been adequately reflected in literature , legislation, labour or social history in this country. The main reason for this neglect was probably lack of knowledge about domestic service and certainly an absence of a comprehensive view of the industry. The work place of the servant was the middle or upper-class home, and the home in Ireland and Great Britain was a private haven into which no outside interference was tolerated or indeed contemplated. Significantly, a bill: to regulate the hours of work, meal times and accommodation of domestic servants and

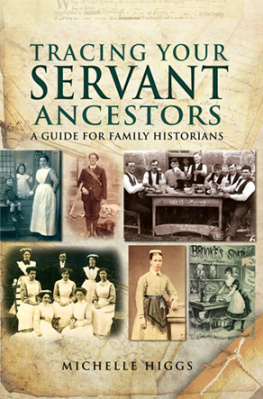

The vast majority of Irish servants were children of small farmers , estate workers, the semi-skilled and the unskilled. The girls, unlike the daughters of the middle and upper-classes, were expected to earn their living until they got married. The lack of alternative employment in Ireland meant that they had a very limited choice; in fact the choice facing them was usually service or emigration . Those who emigrated very often entered service in their adoptive country. Because service was usually the only choice available it became the traditional haven for women from rural Ireland and from many towns and cities. This in turn added its own momentum, so that positions as servants were sought automatically without consideration of alternatives which might, in some cases, particularly at the end of the period, have in fact existed, in factories, shops or offices. Mothers and fathers anxiously looked for situations for their daughters, and to a lesser extent for their sons, as the time for leaving school approached. Help was sought from neighbours, shopkeepers, teachers, clergy and roundsmen, someone was bound to know someone who was looking for a little girl to help with the housework. These first places were often poorly paid but were regarded as an opportunity to learn and perhaps save a little money for the uniform needed for gentlemens places. One former servant who left school at eleven years of age, went to work for a farmer to mind a child who had a cleft palate. She was treated as one of the family, called the farmer and his wife daddy and mammy, but got no pay. She then went to another farm near home where she had board and lodging and they dressed her, but she had no regular wage; she

Domestic service appealed to parents, especially as a career for daughters, as it offered board and lodging as well as wages, and was an easy way to make the transition from fathers house to the world of work. It was also acceptable to the ideology of the time which considered the home albeit someone elses home the natural place for a girl or woman: the work was what any woman would do in her own home. It was also the obvious destiny for those without families of their own those from orphanages, industria l schools and reformatories. Finally, a fate, approved by parents and endorsed by society, was accepted by girls, over much of the period, as their natural role in life. Having accepted service, most girls were prepared to be happy and contented with their lot.

Taking up a situation as it was called for an indoor servant was a more traumatic step than taking up a position in most other industries. It involved a complete break with home, friends and a familiar way of life; it entailed living in a dependent and subordinate position in the home of people who were not only strangers, but who were also of a different social class with different habits, values and lifestyle. Many humorous stories are told to illustrate the difficulties experienced by mistresses when untrained girls were exposed to a way of life of which they were totally ignorant. There are few accounts which highlight how harrowing and bewildering an experience this must have been for young girls. Former servants said that they were very lonely; one, from the country, said that in her first place in Dublin she cried for a week.

The employers household embraced the servants whole life. Absolute loyalty to master and mistress was expected. Apart from some limited free time, the servant was always available to see to the wants and comfort of his employer. The total control of servant by master, which was in fact reinforced by legislation, meant that the domestic servant had little discretion over the day-to-day conduct of his life. To what extent domestic servants may have adopted the outlook and values of their employers and may have become estranged from those of their own social class is a fascinating question but one which is extremely difficult to answer. It is one of the reasons sometimes advanced to explain why trade unionism failed in its efforts to attract domestic servants. Samuel and Sarah Adams, who had worked as servants for fifty years, in their book TheCompleteServant, advised young servants that:

as their mode of living will be greatly altered, if not wholly changed, so must be their minds and manners. They should endeavour to discard every low habit and way of thinking, if such they have; and as there will be set before them, by those of superior rank, and cultivated understanding, the best modes of conduct and the most approved behaviour, they will wisely take advantage of the opportunity which Providence fortunately presents to them to cultivate their minds and improve their principles.

The usefulness of the experience gained by domestic servants in helping them afterwards to run their own homes is often given as an advantage of domestic service. The contrary view is also expressed, namely that the style and standard of living in the employers house made it difficult for the domestic servant to adjust to the harsh reality of a working-class home and, perhaps, a subsistence wage.

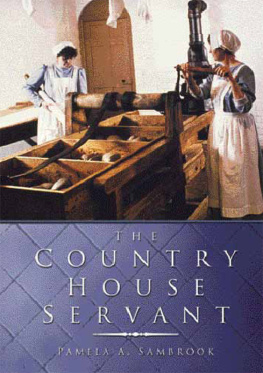

Only a minority of servants in Ireland worked in country houses, yet this world has shaped our image of life below stairs. The reality for the vast majority of servants was very different. Country houses, however, provided the model for the staffing of much more humble homes. The dress, duties, conditions of service and treatment of servants in these houses were adapted by the middle classes to suit their own more modest households, and elements were clearly discernible even in the one-servant home.

Notes

Census of Ireland, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911.

Pamela Horn, The Rise and Fall of the Victorian Servant (London & New York 1975), p.159.

Ministry of reconstruction. Report of the Womens Advisory Committee on the domestic service problem, together with reports by sub-committees on training, machinery of distribution, organization and conditions, p.31 [Cmd 67], HC1919, XXIX, 37.