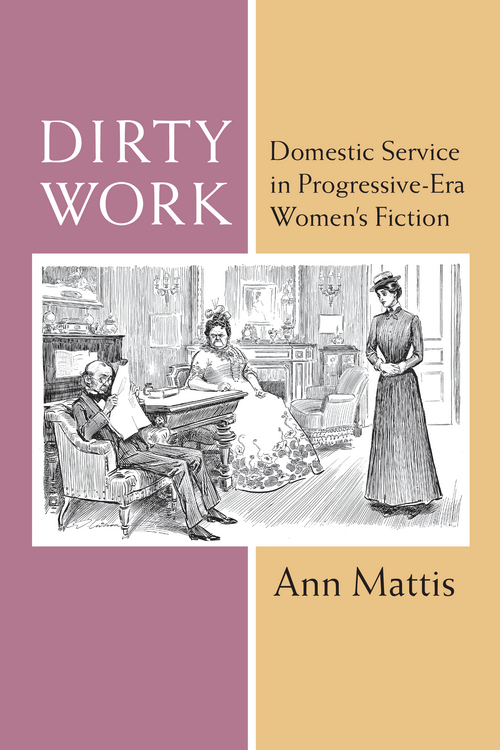

Dirty Work

Dirty Work

Domestic Service in Progressive-Era Womens Fiction

Ann Mattis

University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Copyright 2019 by Ann Mattis

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by

the University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-472-13129-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12507-4 (ebook)

For Helen, my mother

Page vi Page vii Contents

Digital materials related to this title can be found on the

Fulcrum platform via the following citable URL:

https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9450346

Page viii Page ix

I am indebted to my graduate program at Loyola University Chicago, which influenced my intellectual development and provided me with financial resources early on in my career. This book project was inspired by the conversations I had with fellow students and professors in my graduate seminars. Furthermore, the friendships I gained in graduate school helped me through challenging times in my personal and professional life. At Dartmouths Futures of American Studies Institute, I had fine seminar leaders, Colleen Bogs and Eric Lott, and fellow seminar participants who provided me with encouragement and ample feedback that allowed me to situate the project in new critical terms. Also, at an important moment in the writing process, I was fortunate to receive thoughtful and informed feedback from Mary Wilson.

I benefitted greatly from the financial support I received in the form of Summer Research Grants from the University of Wisconsin Colleges. My broad institutional support network on my campus, within the English department and in the Gender, Sexuality, and Womens Studies program, is exceptional, and I am especially grateful to my mentor Amy Reddinger, and my dear campus friends and colleagues: Mark Karau, Valerie Murrenus Pilmaier, Erica Wiest, Thomas Campbell, and Alise Coen. As a research fellow at University of WisconsinMilwaukees Center for 21st Century Studies during the 201617 academic year, I was able to complete final revisions on the book manuscript. I have also benefitted from the conviviality and intellectual support of that interdisciplinary group of scholars, including Kennan Ferguson, the director, and fellows Tanya Tiffany, Jocelyn Szczepaniak-Gillece, Nadine Kozak, Erica Bornstein, and Nan Kim.

Page x Versions of this book have appeared elsewhere in journal form. In 2012, Twentieth-Century Literature published Gothic Interiority and Servants in Edith Whartons A Backward Glance and The Ladys Maids Bell. In 2010, Vulgar Strangers in the Home: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Modern Servitude appeared in Womens Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal.

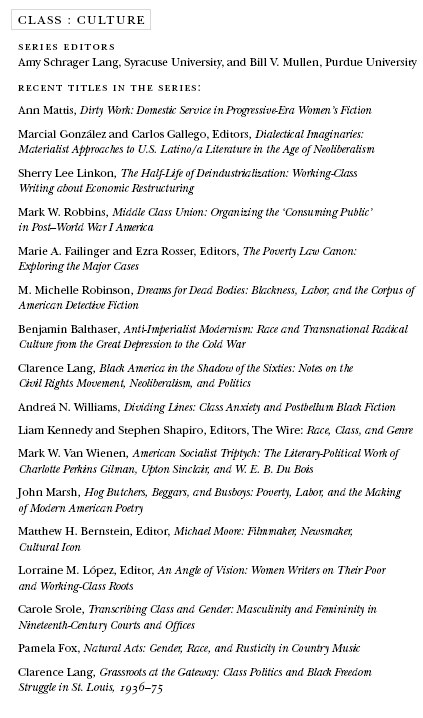

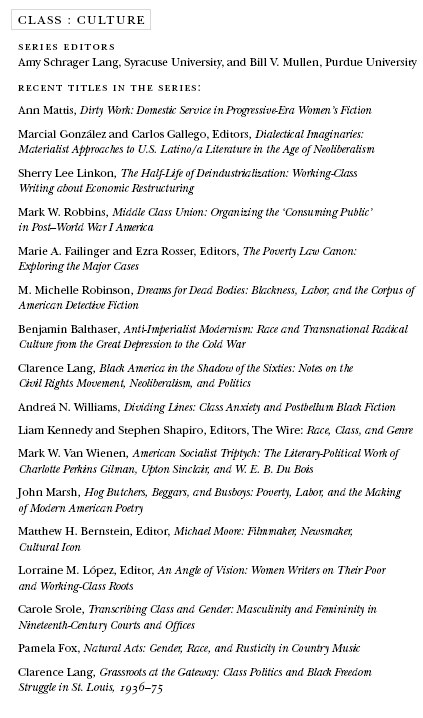

I am grateful to the University of Michigan Press for showing an early interest in this book, especially the acquiring editor, LeAnn Fields, and the series editors of Class: Culture, Amy Schrager Lang and Bill V. Mullen. The anonymous peer reviewers provided extensive and rigorous feedback on the manuscript that challenged me but resulted in a better book.

At critical moments, my emotional and intellectual resources were replenished by old and new friends who have taught me to value connection and intimacy above all other things in life: Derria Byrd, Emily Carroll, Nicola Caso, Krissy Egan, Erin Fagan, Kara Gidcumb, Amanda Gradisek, Amara Graff, Patricia Heary, Shelly Jarenski, Jennifer Johung, Jorie Lagerwey, Zach Lamm, Katherine Lampert, Richard Leson, Laura Loos, Anna Mansson McGinty, Eva Pearce Moller, Valerie Murrenus Pilmaier, Melissa Nepomiachi, Christina Ochs, Inger Rasmussen, Vanya Schroeder, Jocelyn Szczepaniak-Gillece, Tanya Tiffany, Christie Tarsitano, Erica Wiest, and Anne Wingenter. This book would not have been written without the feedback I received from my mentors, David Chinitz and Chris Castiglia, and the intensive support I received from Pamela L. Caughie. I am eternally grateful to my siblings Charles Mattis, Caroline Mattis Muro, and Edward Mattis, as well as my parents, Richard and Helen Mattis, who provided me with inspiration and stellar models of domesticity. My deepest gratitude goes to my baby girl, Claire, who has brightened my domestic life with the purest forms of wonder and delight, and to Bill Malcuit, my very best friend and husband, whose intellect and humor nourishes and enriches every part of me and every corner of my life.

Page 1

American Progressivisms Dirty Work

Livery-clad womendunking soiled linen into soapy buckets, deboning chickens, changing cloth diapers, and scrubbing stoopsare not usually perceived as signaling U.S. modernity or literary modernism. In the dominant cultural narrative of modern womanhood, domestics are eclipsed or superseded by their counterparts in the public sphere: typists, factory workers, shopgirls, telephone operators, and educated professionals. These New Women are reified in the liberal imagination as an irrefutable marker of social progress and emancipated individualism. In contrast, servant girls register as feudal remnants of archaic cultural ritualremains of daysthat precede or exceed modernity in its fully actualized form. Dirty Work sets out to close the imagined gap between gender progressivism and domestic service. In fact, this book reveals how these social phenomena, and their attendant literary tropes, are deeply and intimately intertwined in the American cultural imaginary. As the first book to focus solely on domestic servants in early twentieth-century American fiction, Dirty Work illustrates how the social grammar of American domesticity and middle-class femininity relies upon modern tropes of domestic service that stretch across the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century, but emerged in the Progressive Era.

The popularity of Kathryn Stocketts recent bestseller-turned-blockbuster The Help is a testament to the enduring fascination with domestic service relations in American culture. In its portrait of the American South in the civil rights era, The Help puts domestic service at the Page 2 center of its vision of impending racial and gender progressivisms. The plot yokes together the uprisings of an elite but liberal-minded white journalist and the African American domestic workers in her town. By analyzing this long-standing dialectic, I respond to Lucy Delaps recent call for critics to regard domestic service as a foundational narrative, one that is critical for understanding class, ethnicity, and gender elements of personal subjectivities and identities (2, 236). Literary representations of U.S. domestic service reveal how American domesticities and femininities are driven by class and labor antagonisms. In the Progressive Era, the residue of those antagonisms manifest in a diverse array of womens fiction that prominently features the contact zone of domestic service.

In an era marked by rapid industrialization and womens entry into the public workforce, domestic servants were surprisingly ubiquitous, both literally and figuratively, in early twentieth-century America. They were prominent figures in home economics treatises, undercover journalism, womens autobiography, and training manuals. In these texts, servants were embroiled in a discursive hotbed that was allegedly stoked by their seductive power, abject loneliness, victimhood, incompetence, wrathful disobedience, venereal diseases and unwanted pregnancies, racial inferiority, superior maternal capacity, primitive caretaking, sexual ferocity, comic idiosyncrasies, and, above all, their waywardness. As twentieth-century cultural texts revealed a web of contradictory fantasies and fears about servants, it should not be surprising that servants assume new narrative and thematic functions in a wide variety of genres, including the sampling drawn for this study: Charlotte Perkins Gilmans pedagogical reform novel, Edith Whartons ghost stories, Gertrude Steins modernist prose, Anzia Yezierskas immigrant success novel, Fannie Hursts maternal melodramas, and passing narratives by Harlem Renaissance writers Jessie Fauset and Nella Larsen. Across these various genres, domestic service is a site of fetishization, but also one of complex ideological contestation. In these texts, servants are far from being merely ancillary to the primordial modern family drama; they perforate social myths of a hermetically sealed nuclear family and facilitate the primal web of desire, fear, and identification in female-authored fiction. Narrative conventions harness affectively charged fantasies of domestic service that range from anachronistic to utopian. These new mediations of domestic service, I argue, underlie progressive cultural idioms that articulated new femininities and domesticities under industrial capitalism.

Next page