Also by Paul Krugman

The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008

The Conscience of a Liberal

Fuzzy Math

The Accidental Theorist

Pop Internationalism

Peddling Prosperity

The Age of Diminished Expectations

PAUL KRUGMAN

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

To the unemployed, who deserve better.

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO

THE PAPERBACK EDITION

I PUT THE HARDCOVER edition of End This Depression Now! to bed in February 2012, amid huge uncertainty about what the near future would hold. Who would win the U.S. election in November? Would financial crisis tear Europe apart? And how would the books essential message hold up in the face of events?

Some of that uncertainty has now been resolved. In America, Democrats won a big but not complete election victory: they returned Barack Obama to the White House and expanded their Senate majority, but failed to overturn the Republican majority in the House of Representatives. In Europe, financial markets had calmed down to some extent, largely thanks to support from the European Central Bank, but the real economy continued to deteriorate for most of the continent. In particular, the already terrible situation in southern Europe grew even worse: both Greece and Spain now have higher unemployment than the United States had in the depths of the Great Depression. And during 2012 the euro zone as a whole slid back into recession.

Have any of these events changed the essential message of this book? The answer, unfortunately, is no; on the contrary, the messagethat we are facing a vast, unnecessary catastropheis more relevant than ever. The advanced world remains in depression, with tens of millions of men and women seeking work but unable to find jobs, and with trillions of dollars worth of economic potential going to waste. Yet the evidence is clearer than ever that this depression is gratuitousthat it is the result of nothing more fundamental than inadequate demand. And if governments would reverse their disastrous turn toward austerity and pursue renewed stimulus instead, we could have a rapid recovery.

Lets look at the current situation, and in particular at the prospects for action in America now that the U.S. election is behind us.

Europes Austerity Disaster

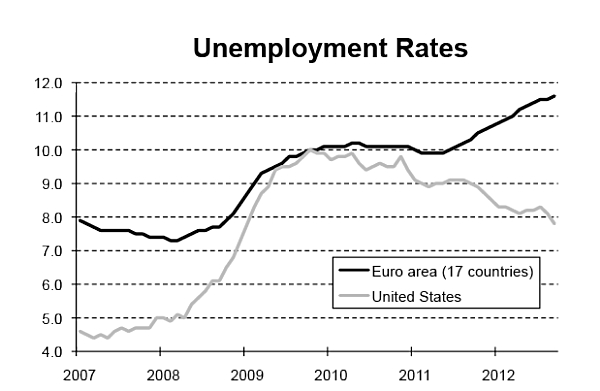

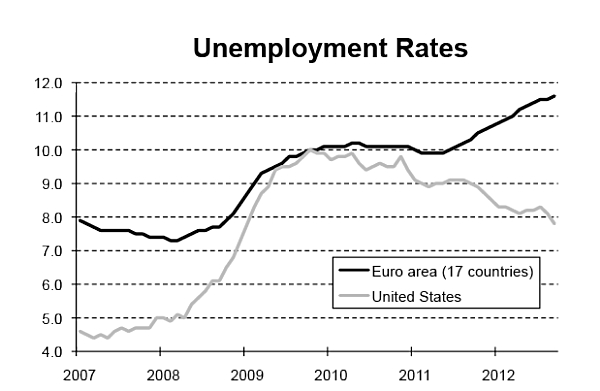

If you want to understand where we are right now, the figure below is a good starting point. It shows unemployment rates in the United States and in the euro area, the group of mostly wealthy European nations that have adopted the euro as their common currency. It illustrates two key points: the two sides of the Atlantic shared a crisis from 2007 to 2010, but their situations have diverged since then.

In the early phase, from late 2007 until early 2010, both Europe and America plunged into deep recession and experienced rapidly rising unemployment. The rise was sharper in the United States, where its much easier to fire people than it is in most of Europe, but in any case the whole North Atlantic economy suffered the worst blow since the onset of the Great Depression.

Starting in 2010, however, the two sides of the Atlantic began to diverge. On one side, America started adding jobs. Although the initial fall in unemployment was partly a statistical illusion (as explained below), by 201112 a clear trend of economic improvement had emerged. The European economy, by contrast, went from bad to worse; by 2012 the continent was officially back in recession.

What accounts for this divergence? The explanation can be found in chapter 11, which describes how 2010 marked the sudden rise of the Austerians, who insisted that governments impose spending cuts and tax hikes even in the face of high unemployment. In the United States, where Austerian doctrine made only limited inroads, there was nonetheless some de facto austerity because of cutbacks by state and local governments. In Europe, however, the Austerians dominated the policy discussion. Savage austerity was made a condition for aid to troubled debtor nations. To get a sense of perspective, consider that if America were to undertake spending cuts and tax hikes on the scale imposed on Greece, they would amount to around $2.5 trillion per year . Meanwhile, countries that were having no trouble borrowing, like Germany and the Netherlands, also imposed at least modest austerity on themselves. So the overall result for Europe was a sharp fiscal contraction.

According to Austerian doctrine, any negative effects from this contraction should have been offset by an improvement in consumer and business confidenceas Ive put it, the confidence fairy was supposed to come to the rescue. In reality, however, the confidence fairy failed to make an appearance. The result is that while America has at least modestly recovered from the effects of the financial crisis, since 2010 Europe has sunk even deeper into depression, with the pace of decline increasing over the course of 2012.

Special mention should be given here to the United Kingdom, which isnt on the euro and as a result has a great deal of policy independence. Britain could have used that independencereflected, among other things, in very low borrowing coststo avoid getting caught up in the European debacle. Unfortunately, the Cameron government, which came to power in 2010, bought fully into Austerian doctrine, perhaps more so than any other advanced-country regime. And while there is some dispute about the relative importance of austerity versus other factors in depressing the British economy, one thing is for sure: Britains economy has performed remarkably badly, with GDP since the onset of the crisis trailing not just America but also the euro area and even Japan.

The good news, such as it is, is that at least some members of the policy elite have acknowledged that they got it wrong. In particular, the October 2012 edition of the International Monetary Funds World Economic Outlook contained a striking mea culpa on the effects of austerity. The IMF acknowledged that after 2010 a number of European economies performed much worse than predicted; and it also acknowledged that these prediction errors were systematically related to austerity programs, with the countries that imposed the biggest spending cuts and/or tax increases falling the most below the forecast. The IMFs conclusion? Under depression-type conditions, fiscal multipliersthe effect of government expansion or contraction on the economyare much bigger than the IMF and other agencies like the European Commission had thought. In fact, the IMF concluded that multipliers are more or less in line with what Keynesians had always claimed.

Unfortunately, at the time of this writing there is little sign that other key players in the European drama are willing to take this information on board. In Greece and in Portugal the troikathe IMF, the European Central Bank, and the European Commissionis still insisting on ever-harsher austerity as a condition for emergency loans, despite overwhelming evidence that the treatment is killing the patients. And while the central bank has declared itself willing in principle to buy the bonds of troubled nations like Spain and Italy, it has also made it clear that Spain, which is already engaged in severe austerity, would have to do even more as a condition for such purchases.

What would it take to save Europe? The recipe I offered in chapter 10 is still the best hope: less savage austerity in debtor countries, at least some fiscal expansion in creditor countries, and expansionary policies from the European Central Bank that aim at somewhat higher inflation for Europe as a whole. Its unclear, however, whether or when such ideas will become politically acceptableand its also not clear how much time Europe has.

Next page