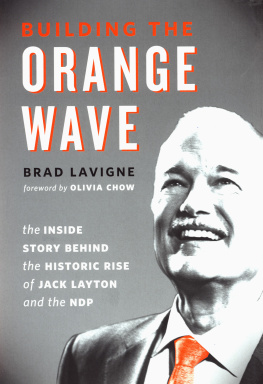

Copyright 2013 by Brad Lavigne

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777 .

Douglas and McIntyre ( 2013 ) Ltd.

PO Box Madeira Park, B.C., V N H

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

isbn 978-1-77162-017-8 (cloth)

isbn 978-1-77162-018-5 (ebook)

Editing by Barbara Pulling

Copy editing by Shirarose Wilensky

Indexed by David Baughan

Jacket design by Naomi MacDougall

Print edition text design by Anna Comfort OKeeffe

Jacket photographs by Erin Jacobson

I mmediately after the election, Jack instructed his new critics to reach out to their government counterparts to explore areas of common concern. A student of our partys past, he knew that some of the finest initiatives in Canada had been done in minority Parliaments.

Tommy Douglas, the father of medicare, worked with Lester B. Pearson to get the Medical Care Act passed in 1966. The Canada Pension Plan and the Quebec Pension Plan were also products of Pearsons minority government. Under the 1972 Pierre Trudeau minority government, ndp leader David Lewis helped bring in national social housing, changes to the political financing laws and steps to ensure greater domestic ownership of Canadian energy resources.

New Democrats had also been successful in minority Parliaments at the provincial level. In the late 1970s, Stephen Lewis, head of the Ontario ndp , worked with Progressive Conservative premier Bill Davis to pass a series of progressive laws. In Saskatchewan, when ndp premier Roy Romanow was re-elected to a third term with a minority government in 1999, he listened to the message sent by the electorate and created a governing coalition, appointing Liberal mla s to the Cabinet. What followed was stable progressive governance for the people of Saskatchewan, for which the ndp was rewarded with an outright majority win in 2003. It was a sensible approach and a smart political calculation.

The Liberals under Paul Martin had another approach in mind. Only a couple of ministers bothered to respond to the outreach from our critics. After a decade of majority rule, it appeared the Liberals meant to hold on to their power as tightly as they could. The rhythm of the [2004] campaign was one of having clouds of shit rain on us from the opening day for weeks on end, and so to come out of that campaign holding on to the reins of government felt pretty good, Martins chief of staff, Tim Murphy, would later explain.

The Liberals had to figure out how to get a Throne Speech passed when the House of Commons reconvened in the fall. To get through that confidence vote, they had two options. They could open up a dialogue with the opposition, or they could draft a Throne Speech on the assumption that one of the opposition parties would let it pass.

When Martin finally invited Jack to 24 Sussex Drive on August 23, 2004, Jack had high hopes for the meeting. I was particularly aware of the real possibilities that existed because, after all, thats why we were here. At least, thats what I thought, Jack wrote later in Speaking Out Louder, referring to moving forward on a series of initiatives for families. As I would hear over the next hour, and amplified over the next several months, this, however, was not a Liberal prime minister or a Liberal Party preparedor even inclinedto work with New Democrats in the way prime ministers Pearson and Trudeau had.

Martin even joked at their meeting that the wellspring of common values between the Liberals and the New Democrats that he so successfully explained in the campaign might run dry pretty quickly, Jack recalled. He left the meeting thinking, Is that all there is?

As Tim Murphy would later admit , the Liberal strategy was to build up public support for the content of their first Throne Speech. The Prime Ministers Office believed the ndp would be forced to vote with the government if the speech included issues that the ndp had run on in the 2004 campaign, such as new funding for cities and helping aboriginal communities. According to Murphy, the Liberals were not interested in opening the kimono from the get-go.

Events didnt roll out the way Martins team planned, and the shenanigans in the weeks leading up to the vote on the Throne Speech sowed seeds of mistrust among all parties that would come to define the minority Parliament. Not long after his disappointing meeting with Martin, Jack met jointly with Conservative leader Stephen Harper and Bloc leader Gilles Duceppe in Montreal. The informal affair, organized by Duceppe, produced a package of joint amendments for the upcoming Throne Speech. Jack didnt think the passage of the speech merited a showdown. He just wanted a nod from Martin about his willingness to give a little. Duceppe and Harper, though, decided to ratchet up the rhetoric. Martin responded to their brinkmanship by freezing out the ndp and striking a deal with the other two parties just an hour before the confidence vote. Jack learned about the deal from news reports.

It was an inauspicious start to a political season that played out on two tracks. Inside Parliament, the prime minister had a barren legislative agenda and couldnt decide whether he was going to stand up to George Bush on missile defence. In February 2005, The Economist would dub Martin Mr. Dithers. Outside Parliament, the Gomery Commission looking into the sponsorship scandal was doing severe damage to the Liberal brand.

Justice John Gomerys inquiry sucked up all the political oxygen in the media. Jack had trouble getting attention, despite the ndp s smart and strategic campaign against missile defence leading up to and following Bushs keynote speech in Ottawa on December 1. During the trip, Bush said he hoped Canada and the U.S. would move forward together on the issue. But the daily coverage about Liberal corruption considerably weakened Martin, especially after appearances before the commission by Chrtien and Martin himself. This new dynamic would play to Jacks advantage during the budget negotiations.

Paul Martin certainly hadnt planned to engage with Jack in any negotiations. In January, Jack was on board a special flight with the prime minister and the opposition leaders en route to Phuket, Thailand, to tour the devastation after a Boxing Day tsunami. Jack was disappointed with Martins approach to governing in a minority Parliament, the first in twenty-five years in Canada, so he took the opportunity on the long flight to talk to Martin, knowing the federal budget was coming up. Martin didnt mince his words. Jack, youre two votes short, he said.

By February 2005, the governments budget was at the printer, but the Liberals still had no dance partner. They were gambling that one of the opposition parties would vote for it, part of the explicit Liberal strategy to govern on a vote-by-vote basis. It wasnt clear at that point that either the ndp or the Conservatives were going to bring us down [on the budget], recalls Tim Murphy. But the Liberals figured all along that there would be a confidence motion before the budget could be voted on. The government was in survival mode, and everything they did was about positioning the Liberals for the next election, thinking it was coming soon. Murphy talked to the Liberal campaign director once a week during this period, in case the government fell. These were tense days, he remembers.

Next page