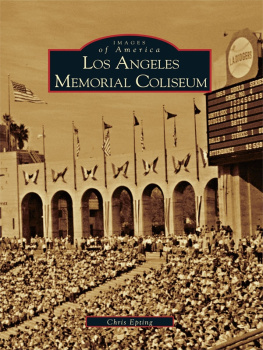

MODERN COLISEUM

MODERN

COLISEUM

STADIUMS AND AMERICAN CULTURE

BENJAMIN D. LISLE

This book is made possible by a collaborative grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

ARCHITECTURE | TECHNOLOGY | CULTURE

Series Editors: Klaus Benesch, Jeffrey L. Meikle, David E. Nye, and Miles Orvell

Copyright 2017 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Lisle, Benjamin D., author.

Title: Modern coliseum : stadiums and American culture / Benjamin D. Lisle.

Other titles: Architecture, technology, culture.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2017] | Series: Architecture, technology, culture

Identifiers: LCCN 2016049590 | ISBN 9780812249224 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: StadiumsSocial aspectsUnited States. | City planningUnited States. | City planningSocial aspectsUnited States.

Classification: LCC GV415 .L57 2017 | DDC 796.406/8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016049590

CONTENTS

Past to Future: The Stadium and Modern

Progress

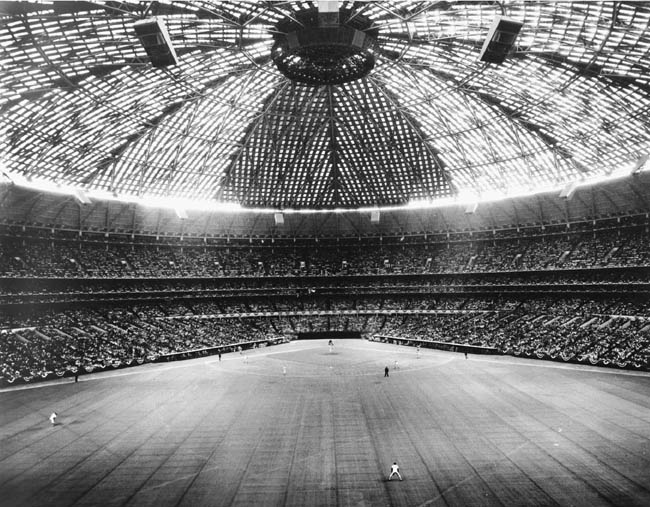

GRIFFITH STADIUM DREW FANS FROM ALL OVER the District of Columbia and its suburbs to attend baseball and football games in the 1950slike a street lamp draws mosquitoes, one area resident recalled. The park was distinctive. Its stands framed an asymmetrical field; the outfield fence cut and jagged around the far reaches of the lot as if it were a stumbling drunk, just dodging a massive tree and five row housesproperty the builders were unable to acquire in the ballparks first days. The winking, mustachioed mascot for National Bohemian beer peeked above the right-field wall as if he were trying to scramble over it. Like so many other old ballparks, this one was squeezed by the neighborhood, producing an effect of either warm embrace or uncomfortable claustrophobia, depending on ones mood and inclination. It was located on the east end of the U Street corridorone of the countrys centers of African American life and culture. Howard University was blocks away. Ralph Bunche, Josh Gibson, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Thurgood Marshall all lived nearby at one time or another. Duke Ellington had once worked at the ballpark, selling peanuts, candy, and cigars.

Griffith Stadiumand U Street more generallywas one of the citys main sites of interracial, interclass congress. A trip to Griffith Stadium was no doubt a logistical trial, but it was also one charged with urban excitementand perhaps the most sustained exposure to African American and working-class urban life for most white visitors. It was certainly one of the few times that white people had to walk African American turf.

FIGURE 1. Griffith Stadium in 1955. REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF THE DC PUBLIC LIBRARY, STAR COLLECTION. WASHINGTON POST.

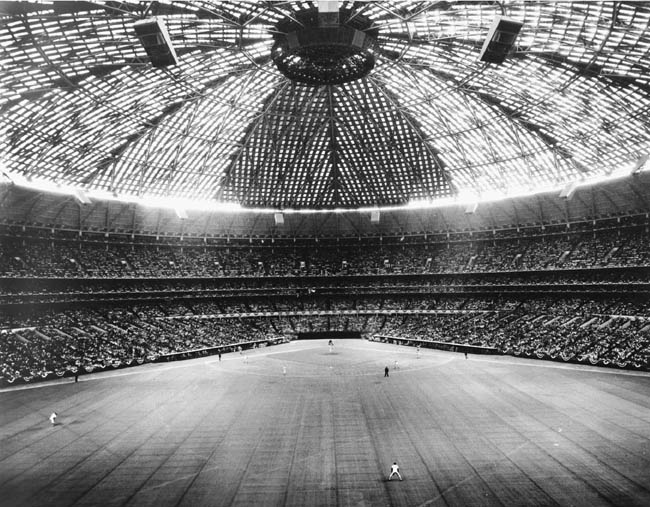

All this modern progress came at a cost. A Post columnist noted, Some of the old-line... fans complain the new D.C. Stadium doesnt have the intimacy of old Griffith Stadium.... Its something like having a party in an austere drawing room after being accustomed to gathering in the kitchen. The sense of urban intimacy and public contact, characteristic of old Griffith, had been lost in a new stadium remarkable for its spaciousness, comfort, and modernist novelty. It was in the city but seemed to share more with the suburbs. The outside world, save the sky above, was invisible to most inside. The circular stadium possessed its inhabitants as though they were in a protective womb. The experience of U Street, and the unpredictable city, had been eliminated.

Variations on this theme were played across the United States, beginning in the mid-1950s, as new modern stadiums were built for major league baseball and football teamseither to replace aging structures or to lure other cities clubs to new pastures. At the end of World War II, most urban stadiums were privately owned affairs that had been built three decades before for professional baseball; they doubled as stages for professional and college football, political speeches, religious gatherings, concerts, and other big events. At the time of their construction, typically in the decade before World War I, these ballparks had marked a new era for spectator sport. Built of brick, concrete, and steel, their permanence contrasted starkly with the wooden firetraps they replaced. Their architectural flourishes marked them, in the eyes of their builders, as challenges to other forms of middle-class leisure like vaudeville theater and amusement parks. Many were even located in middle-class neighborhoods. But by the 1940s, after years of economic depression and war, most were nestled into materially deteriorating neighborhoodsneighborhoods that, like U Street, were either predominantly African American or becoming so. The ballpark scene had become mixed class, interracial, and often rather rambunctious. These were sites of genuine urban diversity, inside and outside the stadium walls.

FIGURE 2. The new, sculptural District of Columbia Stadium under construction in the late 1950s. REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF THE DC PUBLIC LIBRARY, STAR COLLECTION. WASHINGTON POST.

The stadiums that replaced them in the decades after World War II erased much of that urban diversity. Postwar modern stadiums relocated sports space from old urban neighborhoods to open sites along freeways, convenient to booming white suburbs or as anchors to clean-sweep downtown redevelopment. Unlike aged ballparks stitched into neighborhoods, modern stadiums stood like monuments alone amid sprawling parking lots. Ballparks had been boxes, filling up every inch of their rectangular urban lots; modern stadiums were circles, allowing an easier (and more symmetrical) adaptation from baseball diamond to football grid. Old grandstands were stacked one atop the other on vertical support posts. New stadiums cantilevered their second decks, eliminating view-obstructing columns; this also allowed these stadiums to breathe by pushing fans further from the field and releasing some of the pent-up energies that could electrify an unruly crowd. Employing the stark and monumental geometries of engineered modernist architecture, these stadiums were material critiques of the old city and pronouncements of a new modern erapronouncements that were always heavily subsidized, if not entirely funded, by public dollars.

Next page